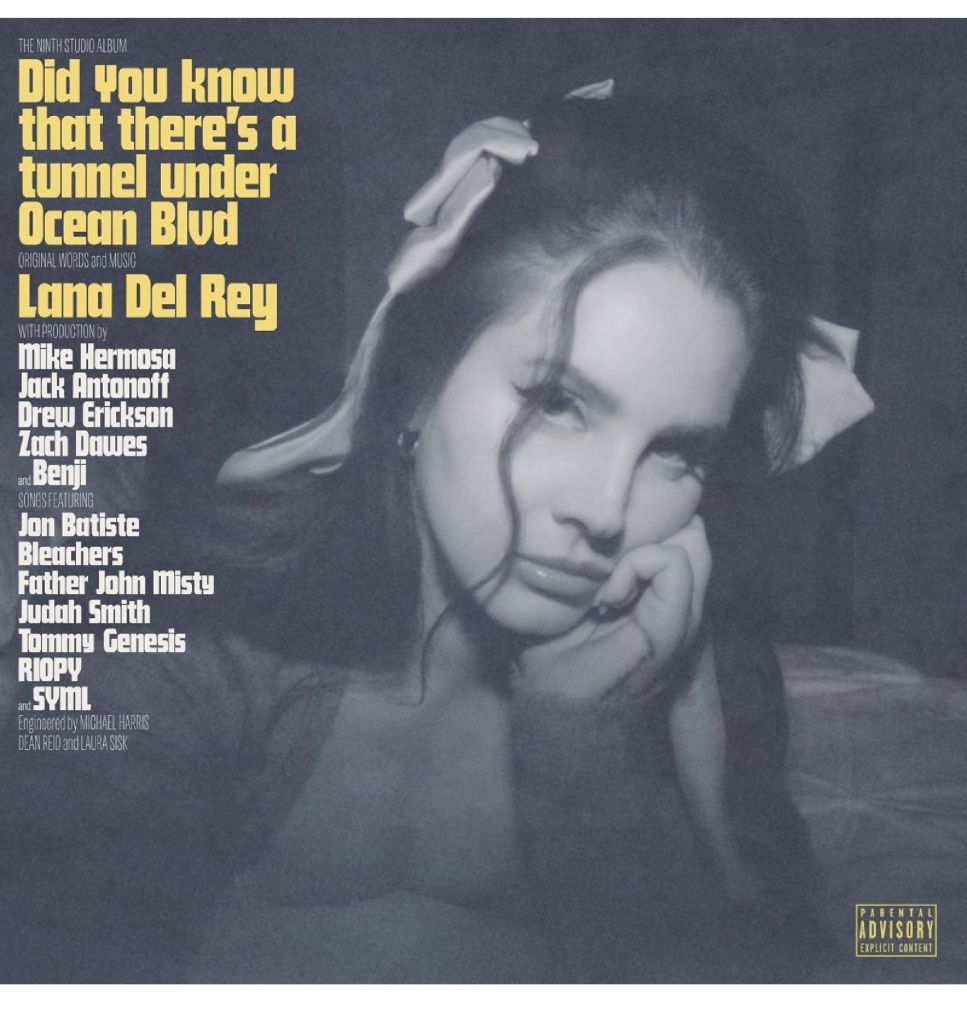

Over the past few years, Lana Del Rey has been engulfed in acclaim: Variety’s Artist Of The Decade, the first recipient of Billboard’s Visionary Award and Rolling Stone UK’s endorsement as ‘the greatest American songwriter of the 21st century’. Bruce Springsteen has named her ‘one of the best’ and Courtney Love called her a ‘true musical genius’. And now, with her long-awaited ninth studio album Did You Know That There’s a Tunnel Under Ocean Blvd released last weekend, the critics have not held back. From the Guardian to the Financial Times, Del Rey’s new album has collected a string of 4- and 5-star ratings.

But to call Del Rey’s journey a bumpy one would be an understatement. Just over a decade ago, the release of her major-label debut album Born to Die, defined by its dark lyricism against lofty orchestral-pop soundscapes, was panned. ‘Awkward and out of date’, Pitchfork branded the album, before likening Del Rey’s melancholy to ‘a fake orgasm’. Critics doubted the authenticity of Del Rey’s sixties Hollywood-inspired femme fatale theatrics. And if her lyricism received the occasional praise, her vocals did not. ‘Her voice is pinched and prim, and her song doctors need to go the fuck back to med school’, wrote Rolling Stone’s Rob Sheffield.

Despite the reception, her allure still captured the attention of many listeners, myself included. I’d occasionally feel like her defence solicitor, which proved tough when the singer would boast that her ‘pussy tastes like Pepsi cola’ and she ‘wears her diamonds on Skid Row’ (‘Cola’), while provocatively whispering ‘money is the reason we exist’ (‘National Anthem’). But Born to Die was, in my view, a blueprint for a nameless genre: a wily critique of the American dream, rooted in irony.

Her following albums peeled back more layers, but the theme remained. Whether it was the psychedelic rock addressing the throes of an abusive relationship on Ultraviolence (2014), the airy vocals and twangy strings underscoring an agonising romance on Honeymoon (2015) or the piano ballads accompanying the bittersweet fluctuation between the Californian dream and its reality on Norman Fucking Rockwell! (2019), Del Rey’s lyricism defies any single reading. The sometimes flawed Americana she explores isn’t exclusively geared to those physically in the United States, or wishing to be. Rather, Del Rey’s take on the American dream is a scrutiny of perfection and our emotional ideals. Del Rey embraces the human battles: balancing hope with despair, lust with heartbreak, liberty with constraint.

There came a tipping point. In the spring of 2020, her long-brewing dissatisfaction with her critical reception led Del Rey to unleash her ‘Question for the culture’ Instagram essay:

‘Now that Doja Cat, Ariana, Camila, Cardi B, Kehlani and Nicki Minaj and Beyoncé have had number one songs about being sexy, wearing no clothes, fucking, cheating etc – can I please go back to singing about being embodied, feeling beautiful by being in love even if the relationship is not perfect, or dancing for money – or whatever I want – without being crucified or saying I’m glamorizing abuse??????’

Del Rey advocated for softness, for the woman who would sometimes assume the passive or submissive role in relationships, and find herself overshadowed by stronger women. To little surprise, an online backlash followed – most notably unfounded accusations of racism, ‘white fragility’, a ‘Karen’ attitude – and her intentions were quickly discredited. Her concern remained, however: popular culture is often less receptive to transparency. But Del Rey sought to break the mould, rather than fit into it.

And it’s evident. ‘Venice Bitch’ was a nine-minute ballad destined to never find its way onto radio airwaves; she wailed like a saxophone on ‘Living Legend’. And now, the 16-song Did You Know That There’s a Tunnel Under Ocean Blvd may just be her chef-d’oeuvre. At points Del Rey’s vocals decouple from the instrumentals, and her backing vocalists false start; she cackles, exhales, screams, sneezes; we hear her vape crackle. She has let loose. Bizarre, maybe, but it’s a welcome antidote to the disposable melodies of many of her peers.

No doubt it’s a somewhat challenging listen. But that’s its virtue. A big portion is Del Rey seeking answers and wisdom in her family. With the orchestral opening track, ‘The Grants’, we see a different approach to romance and her femininity. She questions her chances at motherhood, confronting the realities of biology’s clock on ‘Fingertips’, a five-minute track that the singer warns ‘isn’t good, but explains everything’: ‘Will I have one of mine? Can I handle it if I do?’ She compares herself to the closed and forgotten Jergins Tunnel under Ocean Blvd in Long Beach, California throughout the title track: ‘I can’t help but feel somewhat like my body marred my soul. Handmade beauty sealed up by two man-made walls … when’s it gonna be my turn?’

The seven-minute track ‘A&W’ is a favourite. With its gentle acoustic opening, reflecting on her absent biological mother during childhood and over-sexualisation during adulthood, a soft-spoken Del Rey plunges us into the dark, calmly asking, ‘if I told you I was raped, do you really think that anybody would think I didn’t ask for it?’ Moments later, the folk-pop shapes into a seductive and heavily produced trap sound, with Del Rey’s screaming ‘it’s lit’ and rapping about ‘Jimmy’ and ‘cocoa puff’ (cereal brand or cocaine cigarette?).

Del Rey has long been misunderstood. But rather than succumbing and sacrificing her sincerity, she’s taken it in her stride. The result is the perfectly messy poetry of Ocean Blvd.

Comments