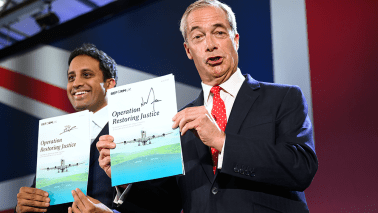

It has become an article of faith in some quarters that the UK’s withdrawal from the European Convention on Human Rights (the ECHR) would breach or undermine the Belfast (Good Friday) Agreement. The Prime Minister, Keir Starmer, played this card only last week, in response to the Reform party’s proposals for addressing illegal migration. For her part, the Leader of the Opposition, Kemi Badenoch, said that ECHR withdrawal ‘could affect the Good Friday Agreement and needed to be done in a way that would not destabilise the country or the economy’. Even Nigel Farage, the leader of the Reform party, seemed to concede the point, saying that the Belfast Agreement would need to be ‘renegotiated’, implying that without a new agreement, UK withdrawal from the ECHR would be a breach.

This apparent consensus is wrong. In a new Policy Exchange paper, published today, Conor Casey, Sir Stephen Laws and I consider the Belfast Agreement in detail, showing that it does not forbid the UK from exercising its right in international law to withdraw from the ECHR. Whether the UK should withdraw from the ECHR is a separate question. But the debate should be fought on the merits, not cut short on the spurious ground that the UK has already promised not to leave.

The Belfast Agreement is made up of two closely related agreements. The first is the British-Irish Agreement, which is a treaty between the UK and Ireland. The second is the Multi-Party Agreement, which is a political agreement between the British and Irish governments and several different political parties of Northern Ireland, an agreement that provides the foundation for the peace process. This political agreement turns in part on various commitments made by the British government and the Irish government.

The simplest way to achieve this end might be to maintain the law of Northern Ireland as it stands

The British-Irish Agreement does not refer to the ECHR at all and none of its terms suggest in any way that the UK or Ireland were undertaking to remain member states of the ECHR in perpetuity. The British-Irish Agreement does note that the UK and Ireland are both ‘partners in the European Union’, but no one is seriously suggesting that the UK’s withdrawal from the EU is in breach of the terms of the agreement.

In signing the British-Irish Agreement, the UK and Ireland agreed ‘to support, and where appropriate implement, the Multi-Party Agreement’. This obligation does not simply make the terms of the Multi-Party Agreement binding on the UK and Ireland in international law, but instead requires the British government and the Irish government to do their best, as they see it, to make the political agreement work over time.

The Multi-Party Agreement does include several references to the ECHR. The context, which includes the troubled history of Northern Ireland and fears about the risks of abuse of devolved power, makes it very clear that these references concern the importance of the law of Northern Ireland imposing limits on the new Assembly and on public bodies exercising devolved power. Each reference to the ECHR in the Multi-Party Agreement concerns the domestic law of Northern Ireland and has nothing whatsoever to do with the individual right of petition to the Strasbourg Court or, more generally, with the UK or Ireland’s acceptance of the Court’s jurisdiction or its developing jurisprudence as a matter of international law. British or Irish withdrawal from the ECHR would in no way undercut, breach or cut across the Multi-Party Agreement.

The enactment of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 and section 6 of the Human Rights Act 1998, insofar as it applied to Northern Ireland, discharged the British government’s commitment to incorporate the ECHR into the law of Northern Ireland as a safeguard against the abuse of devolved power. The commitment concerns public bodies exercising devolved power and not the British government itself and, certainly, not the Westminster parliament. If a future government withdraws the UK from the ECHR, the UK’s duty to support the Multi-Party Agreement can continue to be met by maintaining limits in the law of Northern Ireland on the devolved institutions and on public bodies exercising devolved power.

The simplest way to achieve this end might be, in effect, to maintain the law of Northern Ireland as it stands, but what matters is the substance of restraint and reassurance, rather than particular legal form. The spirit of the Multi-Party Agreement does not forbid ECHR withdrawal, but rather requires the British government to engage the different parties in discussion about how, or whether, to amend the law of Northern Ireland after the UK leaves the Convention. Such engagement should provide reassurance that there will be no diminution of the rights that the agreement was concerned to protect and that there will be no change in the constitutional status of Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom. This would be engagement with the participants within the spirit and the terms of the Belfast Agreement, not renegotiation of the agreement.

The UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement also refers to the ECHR. However, this treaty is not some kind of a second lock on ECHR withdrawal. On the contrary, the Trade and Cooperation Agreement clearly anticipates that the UK or another member state, such as Ireland, might leave the ECHR and then makes provision for trade and cooperation to continue nonetheless, subject to a right of termination. In entering into this agreement, the UK and Ireland (as an EU member state) have jointly accepted that ECHR withdrawal would not undermine their existing obligations under the British-Irish Agreement, including in relation to the Multi-Party Agreement.

Whatever the merits of UK withdrawal from the ECHR, nothing in the Belfast Agreement rules it out as a viable course of action. In his foreword to our Policy Exchange paper, Jack Straw, a significant member of the cabinet that reached the Belfast Agreement, also makes this point; Lord Alton, the chair of the Joint Committee on Human Rights, who also opposes UK withdrawal from the ECHR, takes a similar view. In choosing to exercise the UK’s right to withdraw from the ECHR, a future government would neither be flouting the UK’s international obligations under the Belfast Agreement nor failing to respect the political settlement that grounds the peace process.

Comments