Hearing David Cameron’s many references to the ‘good life’ may puzzle younger voters who did not grow up with Richard Briers and Penelope Keith’s sitcom of the same name. The Prime Minister has a fond memory of popular culture of the 1970s: he recently announced his decision not to stand for a third term by quoting a Shreddies advert from the late 1970s (about three being two many) and says the only song he knows by heart is Benny Hill’s 1971 hit ‘Ernie (The Fastest Milkman in the West)’. So we ought not to be surprised about is talking about The Good Life, which ran from 1975 to 1978.

When the writers John Esmonde and Bob Larbey came up with the idea for The Good Life, they were looking for a vehicle for Briers, who’d just turned 40. He was well established but not quite famous — the other three actors even less so. Felicity Kendal and Penelope Keith were cast on the strength of their performances in an Ayckbourn play. Paul Eddington was a ‘first eleven light-comedy actor’ (as Briers put it) but he was hardly a household name. In the opening credits, Briers’s name was above the title, the other three were below it. Briers’s Tom Good was the lead; Kendal was ensured a decent role as his wife, Barbara, but Jerry and Margo Leadbetter were initially conceived as supporting characters. However, Paul Eddington and Penelope Keith were so good that after the first few episodes, Briers implored Esmonde and Larbey to write them up. The two writers needed no prompting. The Good Life became a quartet — a comedy of manners with a surprising political subtext.

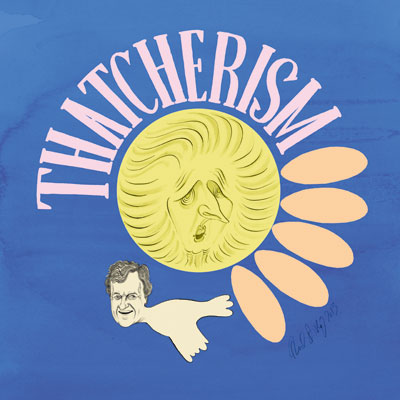

The Good Life was supposed to be about suburban self-sufficiency, but the series soon became a mirror for the fears and aspirations of the age. When the first episode went out, in April 1975, Margaret Thatcher had just become Tory leader and as Penelope Keith’s Margo emerged as a comic counterweight to Richard Briers’s Tom, her character began to sound uncannily like Mrs T. ‘I am not a citizen, I am a resident,’ she declared. ‘I am the silent majority.’ It could (and probably should) have been a Conservative rallying cry.

This was an entirely unconscious process (The Good Life was never sullied by overt satire), but as a house-proud Boudicea who wasn’t scared to speak her mind or knock her neighbours’ heads together, Margo was both heroic and ridiculous — Mrs T writ small. ‘I’m not a complete woman,’ Margo tells Tom. ‘I haven’t got a sense of humour.’ A harridan with a heart of gold, she voiced our growing frustration with ineptitude and apathy (‘There was a time in this country when a date promised was a date honoured,’ she told tardy tradesmen), which would eventually sweep her parliamentary doppelganger into Downing Street. Determined to ‘oust the present rabble’, Margo was a Home Counties Conservative to her fingertips — the series was set in Surbiton and filmed in true blue Northwood. She tried to keep her temper (‘We leave personal insults to the socialists’), but she could put up a fight when she had to. Urbane but ineffectual, her husband Jerry was the archetypal Tory wet.

With their muddy dungarees and baggy jumpers, and their self-inflicted bourgeois poverty, Tom and Barbara Good looked like Chablis socialists, or Liberals at least (in his younger years, Richard Briers bore an uncanny resemblance to Nick Clegg). Yet in their own muddled way, Tom and Barbara also anticipated the Thatcherite revolution. Tom leaves a steady job to be his own boss and start his own business (albeit an extremely inefficient one). They’re happy to scrounge off the Leadbetters, but they have no expectation that the state ought to provide. With his secure career in a vast conglomerate, Jerry is the real dinosaur. As Bob Larbey said a few years ago, ‘It was about a revolution— just one without violence or shouting.’

From 1975 to 1978, The Good Life’s audience grew from 5 million to an average of over 16 million, peaking at 21 million for the 1977 Christmas special (viewing figures virtually unheard of today). It didn’t outstay its welcome, they only made three series. By the time Margo Thatcher became PM, The Good Life was long gone. Not surprisingly, for a TV show that was both conservative and extremely popular, it became a natural target for the middle-class militants of the alternative comedy movement. ‘They’re nothing but a couple of reactionary stereotypes, confirming the myth that everyone in Britain is a lovable middle-class eccentric,’ raged Vyvyan in The Young Ones (a plastic punk played with suitable self-righteousness by Adrian Edmondson). To be fair, there was a distinct element of self-parody in this diatribe, but Edmondson spoke for millions of adolescent anarchists — and I should know, I was one of them. Tellingly, Vyvyan’s fiercest critique is directed not at the show’s prophetic Thatcherism, but its innate philanthropy. ‘I hate it,’ he ranted, splenetically. ‘It’s so bloody nice.’

It’s that niceness which made The Good Life the comedic Aunt Sally of the 1980s (you wouldn’t be seen dead watching it during the Thatcher years — not in my university hall of residence, at least), yet it’s that same unaffected warmth which makes it so watchable today. The Young Ones, so of its time, now feels terribly dated. Conversely, as Bob Larbey observed, the only thing in The Good Life that’s dated is Paul Eddington’s trousers. I came round to The Good Life in the end (it’s called growing up) and so did a few million po-faced students like me. My wife watched it on DVD through both her pregnancies. It kept her sane and happy. Maybe we should have called our children Tom and Barbara (or maybe Margo and Jerry).

It’s usually a bad idea to meet your heroes, but I actually met all the cast, one way or another, and they were all as amiable as you’d suppose. Penelope Keith provided a lovely interview for a BBC documentary I was working on. Paul Eddington gave me a long interview at his home in London’s Docklands, even though he was gravely ill and had to answer my questions lying down. And I opened a door at the Hurlingham Club, came face to face with Felicity Kendal, and was far too star-struck to say anything — this one doesn’t really count, I know, but for me it was the most thrilling encounter of them all. I met Bob Larbey too (happily still with us; John Esmonde sadly passed away a few years ago) and his essential decency shone through.

I met Richard Briers twice and he was charming, but also far brighter than you might imagine. The second time was over high tea at a friend’s home in Chiswick, but it was our first meeting which really lingers in my memory. I’d just started out as a journalist, and had been sent to interview Briers in Norwich, where he was playing King Lear for Kenneth Branagh. I was late, he was late — he only had half an hour, I had a big space to fill — it wasn’t nearly enough time. I was a bag of nerves but he was a total pro, putting me at my ease (even though he was due onstage as Lear in an hour or so) and rattling off his answers like the star guest on a chat show. I came away with more than enough — anecdote after anecdote, funny, clever and insightful. He may have made a cracking Lear, but The Good Life — the show which foresaw the rise of slow food, self-employment and Mrs Thatcher — is the most fitting monument to this unassuming yet gifted man.

Comments