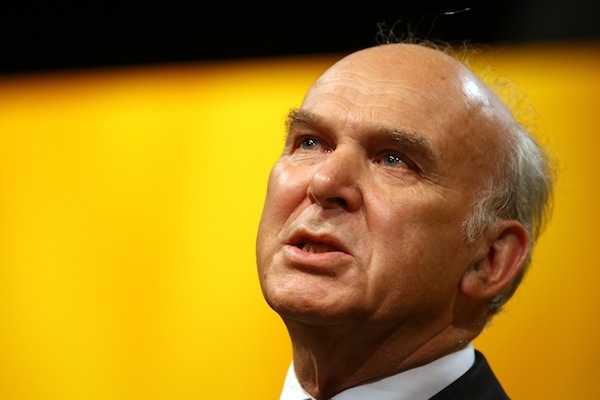

When economists get things wrong– something rather easy, given the nature of their subject – they should admit that they got them wrong. Well, the Adam Smith Institute got it wrong. Two years ago we predicted that, if Vince Cable got his way and capital gains tax rates were increased to match income tax rates – up from 18 per cent to 40 per cent or even 50 per cent – the Treasury would not make anything out of it, and would actually lose £2.48bn in revenue.

In the event, CGT was not raised to 40 per cent or 50 per cent. But it was raised to 28 per cent from 18 per cent for most asset sales. (The entrepreneurs’ rate, designed to encourage people to build up lifelong businesses, remained at 10 per cent.) The result? The Treasury is about £4.9bn worse off than it was before. We were wrong, but only in terms of being far too conservative about the revenue losses that a tax hike would bring. It is time to bring CGT back down to more realistic levels – levels that would encourage people to invest in the UK and in UK businesses and maybe help get us out of our downrated, deficit-dominated doldrums.

The CGT rise came in on 23 June 2010 – unusually, 78 days into a financial year. That was how keen Vince & Co were on it. That is good and bad for economists, as it makes it possible to see how the receipts changed within the same year, though it does make the arithmetic a little trickier. What actually happened is that, on an annualised basis, CGT raised £8.2bn before 23 June 2010, and just £3.3bn afterwards. We told you so, though we didn’t tell you loud enough.

I am sure that high-taxing ministers will brush off much of this difference by saying that because people could see the hike coming they decided to sell off assets before they got hit with the extra tax. And indeed, normal disposals were down 76 per cent after 23 June 2010. Perhaps more surprisingly, entrepreneurs’ rate disposals were also down by 34 per cent – meaning that even people running lifetime businesses got out before the tax changed, just in case they were hit too.

That indicates two things. First, just how far people will go to avoid this tax, particularly when it is levied at rates they feel are simply unfair. After all, much of the capital ‘gain’ that a long-term investor makes is simply inflation, and inflation has been running high for some time. People naturally resent paying tax on ‘gains’ that are not in fact real.

Second, it indicates just how far CGT is a voluntary tax. Very few people are forced to sell assets. If they figure that they will be socked by a big tax, and that the money they will get for their assets will keep losing its value, they will hold on to them, and maybe wait for a change of policy that brings in lower taxes and less inflation. The only people who are forced to sell assets are those like pensioners who build up lifetime savings and then need to sell them to fund their retirement, or expensive episodes of medical or social care.

So high rates of CGT are bad for the Treasury, bad for the ordinary saving public, bad for business investors – and therefore bad for the country. It is time to send out a message that the UK is committed to being a low-tax country, and reduce or even get rid of this damaging tax.

Eamonn Butler is Director of the Adam Smith Institute.

Comments