‘I am 12 miles from a lemon,’ lamented that bon vivant clergyman Sydney Smith on reaching one country posting. He was related to Gerard Manley Hopkins, a priest who, in the popular imagination, would quite possibly balk at the offer of a lemon. After all, 30 years before Prufrock, Hopkins did not dare to eat a peach, fearful of its delicious savour when offered one by Robert Bridges in a Roehampton garden.

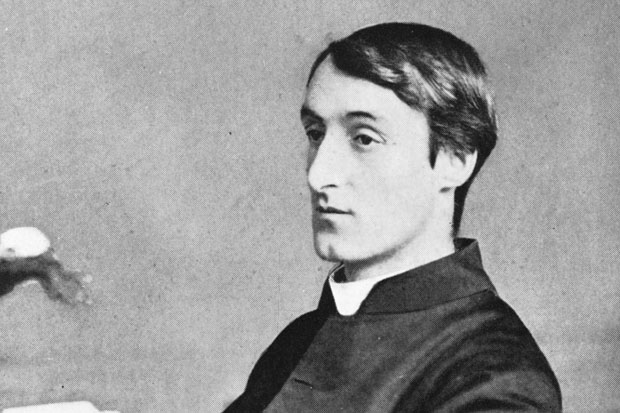

Hopkins was a complex man who delighted in simple things. Our sense of his view of the world has been complicated by the circumstances of his publication. Forbidden to publish his great ‘The Wreck of the Deutschland’, he largely squirrelled away, or burnt, his work. At his funeral in 1889, there was no body in the coffin, lest it spread typhoid; and, three decades on, when Bridges published a collection of his poems, it was almost as if a Harry Lime had sprung forth to find a ready place in a changing, Prufrock-driven literary landscape. It took a decade to sell 750 copies at 12/6, but Hopkins was amongst us.

One of the first to relish him was Virginia Woolf who, in a letter, wrote:

I liked them better than any poetry for ever so long; partly because they’re so difficult, but also because instead of writing mere rhythms and sense as most poets do, he makes a very strange jumble; so that what is apparently pure nonsense is at the same time very beautiful, and not nonsense at all.

Hopkins would be carried forth on the tide of Modernism (Mrs Woolf herself typeset key poems: Hope Mirrlees’s ‘Paris’ and Eliot’s The Waste Land). Muriel Spark’s 1963 novel of postwar life, The Girls of Slender Means, was suffused with ‘The Wreck of the Deutschland’, from elocution lessons to its very ending. Perhaps the apotheosis of this came with Anthony Burgess who, steeped in Hopkins, shared his Catholic background with a relish of music and etymology (Hopkins notes that green wheat has ‘a chrysoprase bloom’). Come 1973, Burgess put Hopkins at the centre of his novel The Clockwork Testament, about the splenetic poet Enderby, whose script for a film of the ‘Deutschland’ is waylaid by the studio so that it features naked, ravished nuns — and lands Enderby on an astonishing New York chat show. Owing something to Burgess’s own dealings with Stanley Kubrick, it is a bravura performance — and a perfectly serious engagement with such notions as original sin which preoccupied Hopkins.

Meanwhile, publication of Hopkins’s surviving papers had shown him very much a man buffeted, and stimulated, by the cross-currents of his times — even when in apparent retreat from them (less than charitable comments about Gladstone are dwarfed by an account of the French face). And now, a century after that first slim volume, everything is being reconfigured into eight stately volumes of the Oxford English Texts. If this one looks expensive, it is cheaper than some secondhand copies of the earlier edition — and, indeed, the parallel volumes of his often debonair letters (his shoe-makers are ‘murderers by inches’) have quickly gone into a third printing.

The journal follows a similar trajectory to the letters: from a comfortable, cultured Essex upbringing — bolstered, ironically enough, by his father’s profiting from the insurance of potential shipwrecks — to a traversal of Balliol, which led to his giving up any hopes of living as an artist in favour of conversion to Rome, and dispatch, as a Jesuit, to many locales, some less congenial than others.

Often intense, the journal dwells on himself, his ailments (piles, circumcision), so much so that it is fitting that school-fellows turned the second syllable of his surname into the nickname of Skin. For all this, it is a record of the close observation from which his poems spring (often in these pages). ‘Unless you refresh the mind from time to time, you cannot always remember or believe how deep the inscape in things is.’ Central to his Scotus-inspired conception of God’s grandeur, this view of the patterns of creation takes many turns amid flora, fauna and, abundantly, the shifting clouds.

He is endlessly quotable (just as the poems read aloud so well). Now first published are his deleted records of sin (as he saw it). Frequent, for some while, is ‘O.H.’ (old habits: masturbation). Not only fixated upon Digby Dolben, whom he met once before he drowned, he looks ‘at a man who tempted me’, ‘looking at a chorister at Magdalen, and evil thoughts’, and ‘looking at a cart-boy from Standen’s shop door’ as well as confessing to ‘self-indulgence at Croydon in fruit’ (a peach?). Odder is ‘looking at and thinking of stallions’ while, at home, ‘evil thoughts from Rover lying on me’. 150 pages later, Lesley Higgins gives the black retriever’s dates (1864–75), typical of exemplary scholarship which, in particular, pays revealing attention to Hopkins’s appreciation of art.

Not only did he look, he saw. That lifted him, hovering above many contemporaries, so that even in prose he still speaks to us: of roses, he notes, ‘the inner petals drawn geometrically across each other like laces of boddices [sic] at the opera’ and his elaboration of a peacock’s feather is as fascinating as his attempt to make a duck follow chalk lines.

Catherine Phillips’s splendid 2007 study of Hopkins and the contemporary ‘visual world’ notes, for example, how waves described and drawn in the 1872 journal ‘each with his own moustache’ surface in the ‘Deutschland’ as being at one with God (‘a motionable mind’). The earlier edition contained a piece by John Piper which noted: ‘Hopkins used drawing primarily to illustrate his ideas for himself. Rarely do the drawings pretend to be anything but analytical descriptions of things.’

Although Piper averred that the artist could not have got ‘the upper hand’, more drawings will be gathered in another Oxford volume, all to be crowned by one for the poems. Of these, T. S. Eliot — in an uncollected lecture due to have been given in Italy early in 1940 — came round to the view that ‘his real place is as the greatest religious poet of his century’. These journals sustain Hopkins on that journey. The self-lacerating passages can be misleading. Hopkins is wonderful company, and we can only regret that he himself did not have more of it.

Comments