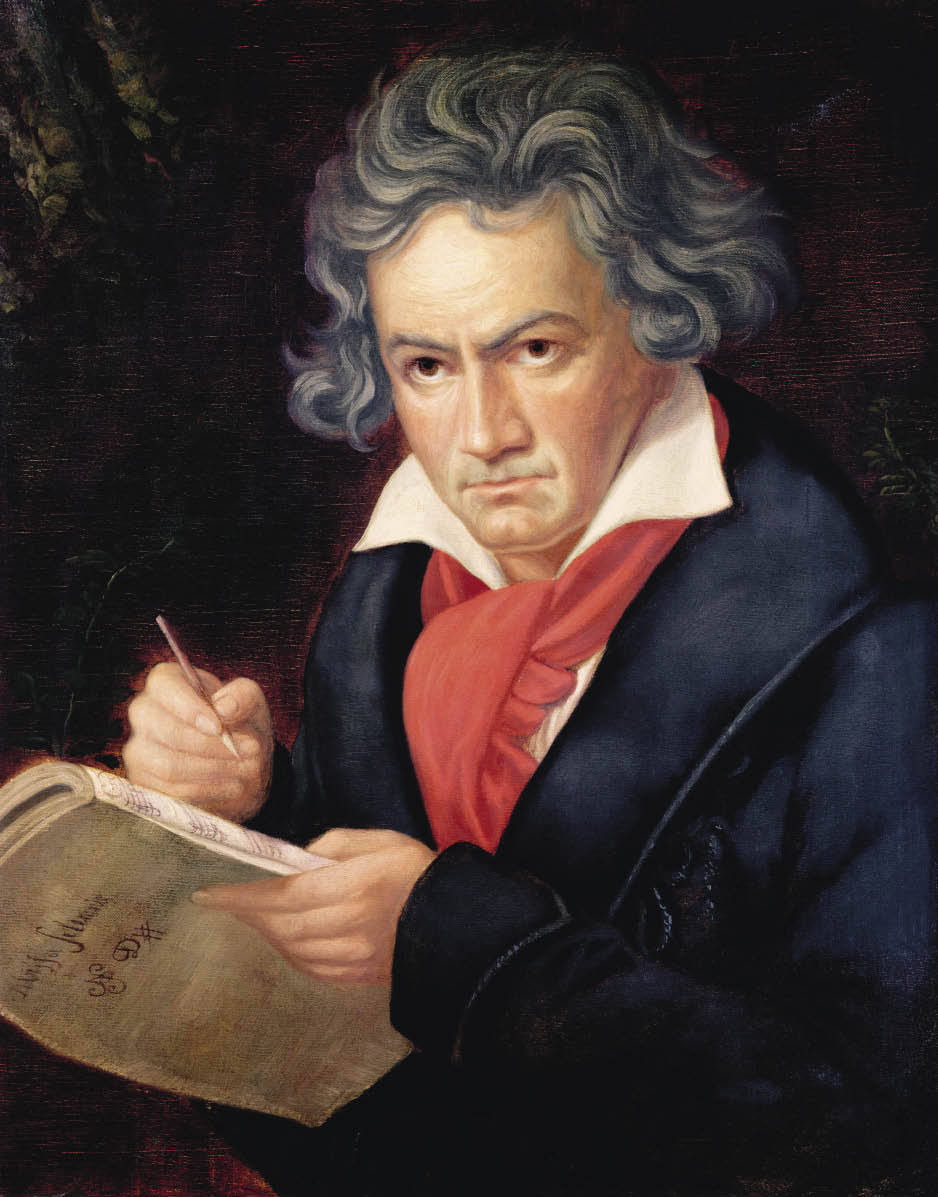

Assailed on all sides by cultural vacuity, we are more than ever in need of the life lessons of Beethoven, argues Michael Henderson

We do not, as a rule, meet all our loves at once. Those things which mean so much to us in our emotional maturity did not always strike us as special presences. Indeed, we may have been suspicious of, or felt hostility towards, some of the supreme works of art, and the minds that created them: many an indentured Wagnerian had first to leap through the magic fire of his initially forbidding music dramas.

Last week, therefore, as I sat in the drawing-room of a house in central London, and watched Gábor Takács-Nagy, founder of the Takács Quartet, supervise another superb ensemble, the Belcea, as they played through Beethoven’s Op. 135, his last work for four instruments, it was with a sense of gratitude and wonder. This was a master-class in the truest sense, five magnificent musicians honouring the greatest of all composers, and from a personal viewpoint it represented the closing of a circle.

Thirty years ago, when I first heard the Op. 135, somewhat bewildered, in a Lancashire vicarage, how was I to know that that quartet, and the 15 which preceded it, would become the musical obsession of my life? A friend had bought me a boxed set of Beethoven’s last five quartets to mark a significant birthday but it was clear from that first exposure that I wasn’t ready for them. Even at this distance, when the music holds me captive to such an extent that I cannot go a week without hearing at least one of those 16 works, I would be suspicious of any young person who said they were.

There is no exclusivity in this view. Ever since Beethoven completed that last quartet, in 1826, music-lovers have known that, to engage fully with these works (to ‘understand’ them is a presumptuous claim, best avoided), one must first have lived long enough to make some sense of one’s life. Beethoven was neither the first nor the last composer to try to reconcile the philosophical abstractions of being and becoming. He just did it with greater profundity, admittedly a rather self-conscious profundity, than anybody before or since.

That is not to deny the genius of Bach, Mozart and Schubert, as if anybody ever could! Nor should one overlook Haydn, from whom Beethoven learned so much, including the most important lesson of all: leaving home. Yet it is the Rhinelander who changed the way we play, hear and think about music, and it is above all in those five late quartets, which Stravinsky said would always sound contemporary, that this deaf man expressed in sound what Wordsworth (who was also born in 1770) sought in words: ‘A motion and a spirit, that impels all thinking things, all objects of all thought, and rolls through all things.’

The two giants had more in common than they knew. Wordsworth published Lyrical Ballads (with a bit of help from Coleridge) in 1798, the year before Beethoven gave the world his set of six Op. 18 quartets. They were both drawn to the revolution in France, before reason and experience dragged them back. And they both changed utterly the maps of their different worlds, even though their work baffled many who encountered it steaming-hot. ‘Profound in conception and admirably written, but not generally comprehensible,’ wrote a Viennese critic when Beethoven published his three Razumovsky quartets in 1807.

Addressing members of the Belcea, Takács used more gentle words for the effect he was seeking. ‘It’s like falling leaves in the autumn.’ Yet autumnal will not suffice as an adjective, even for the latest of the late quartets. All the seasons are there, and all moods, even an impish humour. There is conflict and resolution, a sense of the sublime that is never merely beautiful (Beethoven was not ‘pretty’), and an understanding that all things must pass. Within a year he was dead.

This much is well known. So why do the quartets continue to touch so many listeners so deeply? The first, most obvious reason is that this music has an unprecedented emotional power that repeated exposure can never dull. Although the late quartets plumb the depths of what human beings can feel, it is unwise to imagine the Op. 18 set is no more than prentice work. There, too, you will find an emotional world far removed from that of Haydn or Mozart.

‘The better we know a great work,’ said Alfred Brendel, ‘the more it surprises us.’ Brendel is a master of the keyboard but what he says goes also for stringed instruments. To observe the Belcea responding to the suggestions and gestures of Takács was to understand that great music, no matter when it was composed, lives in an eternal present. Every performance is both the first, and an accumulation — an accretion, if you prefer — of every performance that has ever been given.

There are two other reasons. More than any composer, more even than Schubert, his great contemporary, he measures our growth as sentient beings, just as Shakespeare and Rembrandt do. A person who fails to come to terms with Beethoven has, in some profound sense, failed to live a proper life, or to understand why life is worth living. He is, as Anthony Burgess wrote of Shakespeare, one of mankind’s redeemers.

That surely is the nub of it. On all sides we are surrounded by junk: junk television, junk radio, junk newspapers, junk advertising. The most visible parts of our culture are threadbare. Writers who can’t write are painted as truth-tellers. Artists who can’t draw are hailed as visionaries. Interpretation of the arts is increasingly in the hands of relativists who are hostile to the idea that some things may be better than others. Not that it stops them talking about ‘spiritual’ journeys — ‘two return tickets, please, to Karma Central’.

Falsity assails us everywhere. Yet Beethoven, through his music, always tells the truth. He compels us to listen afresh, and to offer an honest assessment of ourselves and our lives. When we listen to the quartets we hear the still, small voice of calm, which can never be silenced, no matter how angry the voices beyond may be. It is music that offers consolation to those laden with grief, equilibrium to the unbalanced, and, if accepted in the generous spirit in which it was written, will remind the honest listener of (Wordsworth again) ‘man’s unconquerable mind’.

‘Everything good matters,’ Bernard Levin wrote. ‘Nothing bad does.’ In my experience — a partial one, granted, and far from comprehensive — nothing matters more than the chamber music of Beethoven. Those who know the quartets do not need to be told this. For those who stand at the foot of this extraordinary mountain range, as I did three decades ago, fearful of loose rocks and intimidated by the scale of the climb, I would say only this: the views from the peaks are worth it.

Comments