Peyrot, the chef at Le Vivarois in Paris, had a fascinating theory of how one of his regulars, the otherwise taciturn psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, communicated. ‘He was convinced that the farts and burps which Lacan, as a free man, did not restrain in public, were meant to signal to Peyrot the two syllables of his name,’ recalls Catherine Millot. A translator’s footnote helpfully explains that in French pet means fart and rot burp.

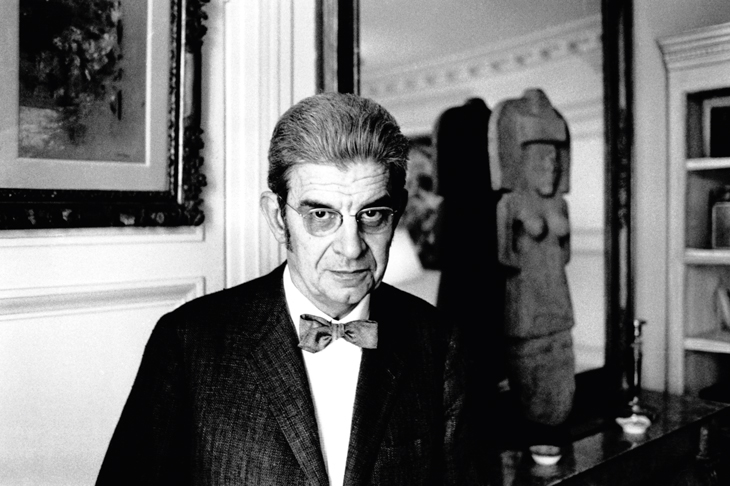

I love this story as told in this beguiling memoir by Lacan’s last lover — and not just because it evokes a time when deference to Gallic intellectuals was such that even their airy nothings were submitted to bravura semiotic analysis. No, I love the story most for the light it throws on the man who some maintain to be the greatest psychoanalytical theorist since Freud but who others have called the shrink from hell. Public farter and unashamed burper, terrifying (to his passengers) flouter of speed limits, shrink who had affairs with patients and ex-wives of close friends, Lacan liked to remind people that his star sign was Aries, the ram.

Millot writes that her ram endlessly butted up against what he called the ‘real’, namely that which resisted his desire. That no doubt explains why he was arrested once for barrelling down the hard shoulder of an otherwise congested autoroute after hitherto stationary and angry French motorists swerved into his path to impede his progress.

Even though French road users hated him, Lacan was, to Millot, captivatingly lawless, someone who ‘paid no attention to prohibitions or conventions’. ‘He didn’t like closed doors any more than he liked red traffic lights,’ she adds approvingly. Well, nobody does, but only a few people — Lacan, sociopaths — don’t respect them.

Millot was being analysed by Lacan in 1972 when she became his lover. He was 70 and she, at 28, younger than his eldest daughter Caroline. Is it unethical, or at least destructive to a therapeutic relationship, for a shrink to seduce his patient? Wasn’t Millot foolish to be captivated by an inveterate philanderer? Is farting in public one of the human rights the French fought for in 1789 or just the hallmark of a very selfish man?

Millot doesn’t address these questions head on, but instead disarmingly describes her sense of the headiness of their affair. ‘We became, so to speak, inseparable,’ she writes, and then immediately checks herself: ‘There was a “he”, Lacan, and there was an “I”, myself, who followed him: this did not make a “we”.’ It’s a remark that calls out for a hashtag of solidarity, a #MeToo of women not always entirely unhappily caught up in the slipstreams of great men. Lacan was, Millot writes, what the French call fusionnel — someone who constantly demanded a presence at his side. There is an English word for that kind of guy, too: nightmare.

No matter. Millot fell for Lacan because of his ‘straightforward desire that gave him his zest for life and simplified everything’. Early on in their affair, he takes her to Rome, deploying his lawless personality to force his way into closed galleries and convents, vexing gatekeepers and sweet-talking nuns in order to show his new lover art and antiquities.

As a fart-concealing, probably thereby deeply repressed, Englishman, I read such passages yearning to be as forcefully antinomian as Lacan and, indeed, wondering how many ex-lovers would be eulogising me in memoirs had I succeeded. ‘All the vanities were consumed in his disdain for everything except the essential,’ Millot writes. ‘Life with him was like a great bonfire, where all false values were burnt away.’ I couldn’t help reading such passages aloud in the sultry voice that another appealing Catherine — Deneuve — brought to her lubricious duet, ‘Dieu est un fumeur de Havanes’, with randy old Serge Gainsbourg, though that’s probably unfair of me.

In any case, Lacan’s desire did not always simplify everything. In the summer of 1973, he was torn between Millot and another lover, called only ‘T’, so he invited both women to join him in a ménage in Umbria. The women declined to take part in this love triangle. ‘It would have taken a strong degree of liking for me to overcome that jealousy whose agonies I knew all too well,’ explains Millot sensibly.

But she insists that Lacan was more than a desiring machine, implacably bent on getting what he wanted. In Budapest, she lusts after a pair of high heels worn by a passer-by. Lacan immediately scampers after the woman to find out where she bought them. Moral? ‘Putting himself at the service of the desire of the other was part of the ethics of Lacan. For him there were no small desires, the least wish was enough.’

Millot’s elegantly written little volume, winner of the Prix de littérature André-Gide, serves as refreshing antidote to those who pigeonhole Lacan as writer of gibberish and irresponsible id, one who indulged his whims to such an extent that he would see his tailor, his pedicurist and his barber in the consulting room during therapy sessions at which he might punch or pull the hair of a patient.

In his textbook on psychoanalysis The Analytic Experience, for instance, Neville Symington refers only once to Lacan, and then only as a case study of the shrink as unwitting hypocrite. Lacan was violently anti-authoritarian and ‘yet when he was in authority over his own society he was enormously authoritarian, seemingly without knowing it’. Indeed, his authoritarian machinations as leader of the L’Ecole Freudienne de Paris figure in Millot’s reminiscences, but glossed as triumphs of his will over humbler beings with, you’d think, less auspicious star signs.

Millot decided to write this book when she was the same age as Lacan was when they became lovers, and so she has had time to reflect on her life with the psychoanalyst, who died 37 years ago. Like Edith Piaf, she regrets nothing. Well, not quite. Once, on a trip to London, Lacan, spotting a picture of the Queen, told Millot that she resembled her — quite a disappointment for someone who hoped she looked like Brigitte Bardot.

It’s hard not to find Millot endearing, particularly when she tells such stories against herself. On another occasion, a lover whom she replaces tells Lacan snarkily that in his new girl he has clearly found ‘the missing link between human and ape’. Millot, superbly, takes the jibe on the chin. ‘I have long arms and a somewhat protruding jaw,’ she concedes.

What did Lacan see in Catherine Millot, apart from a resemblance to apes and queens? He tells her that he has always gone for 30 year olds. The implication is that, for all his philandering, he remained loyally fixated on one woman — albeit the ideal of a thirtysomething — eternally feminine, whose real instances (such as his first lover, whom he met aged 17, and his last, whom he seduced half a century later) serially captivated him as he aged.

The book has hilarious moments. In 1976, Millot and Lacan visit the ageing philosopher and former Nazi Martin Heidegger, who has suffered a stroke. His wife insists the visitors don slippers as they enter. Once settled, Lacan launches into a long disquisition on the Borromean knots that, as Millot explains, became such an important feature of his thought. He even produces a piece of paper to sketch his knots, while Heidegger, lying on a chaise longue, like an analysand driven to desperate measures by his babbling shrink, closes his eyes and says not a word. ‘I wondered if this was his way of expressing his lack of interest or whether it was due to the decline of his mental faculties,’ muses Millot.

Either way, Lacan (‘not a man to give up’) obstinately carries on wittering about knots until Frau Heidegger, concerned the visit is tiring her husband, ushers them out, not before reclaiming the slippers. Such was the meeting of two great European intellectuals. We will never know, presumably, if Heidegger’s silence implied rejection of late Lacanian psychoanalytical theory, but it is possible.

Critics have long suggested that Lacan was a corrupt manipulator, one who in his later years reduced the duration of therapeutic sessions to ten minutes or fewer so that he could maximise the throughput of patients and thereby profit more (he died in 1981, they never fail to point out, a multi-millionaire). Millot’s denouement undermines that cynical image. It was through his work in the consulting room with the woman he loved that, ultimately, Lacan got what he didn’t want, an end to their affair. In analysis, she realised that her great desire was to have a child. ‘In the name of this desire, I cruelly separated from him, so as to have a chance of fulfilling it. It was a wrench for me, and an earthquake for him.’ The ram, so used to getting his way, for once could not overcome the real.

While he was apparently heartbroken until death, she flourished, becoming both a mother and an eminent Lacanian psychoanalyst. And now she brings into being, like Proust, a past that seemed forever inaccessible: ‘While writing I have rediscovered many bygone days and in sudden flashes of insight, the entirety of his being has been restored to me.’ Minus, one supposes, the farts and burps.

Comments