Everyone loves an underdog. It doesn’t matter how incompetent they might be — indeed, incompetence works in their favour. You do not expect underdogs to be adept, do you? It doesn’t really matter how vile, otiose or absurd their beliefs are, either. So long as they are up against someone more powerful, a certain sentimental section of the population will be rooting for them. Look at the Palestinians, for example. And look at Jeremy Bloody Corbyn.

My wife — a Tory — said to me the other day: ‘You lot want to watch it. I’m beginning to feel sorry for the bloke. The sympathy votes will be stacking up.’ We had been listening to some deposed Labour grandee laying into Jezza for his witless, virtue–signalling lapel-badge politics, his managerial ineptitude, his beard, his dress sense, perhaps even the whiff of his breath — lentils stewed in an Irish peat bog for interminable hours — his pre-teen internationalism and his utter estrangement from the electorate.

I was cheering along and agreed with every point. But there is so much to have a go at with Corbyn that in the end it sounds like overkill, like breaking if not a butterfly, then a really crap moth — one of those tiny brown micro-moths even the lepidopterists get bored by — on a wheel. You can feel, when these fusillades rain down, the audience shifting uneasily and the weight of allegiance drifting towards the dull, the stultifyingly dull Marxist idiot. It does not matter how accurate the barbs may be; simply that there are too many of them, one after the other until it becomes a barbarism. And the public, or some of it, thinks well hell, if he can arouse this level of animosity, then he can’t be all bad. Such fury and contempt — maybe, then, he has a point. And they think this even if he doesn’t actually have a point, even if the ‘new politics’ is merely an amalgam of late 1970s radical chic idiocy and the aforementioned incompetence.

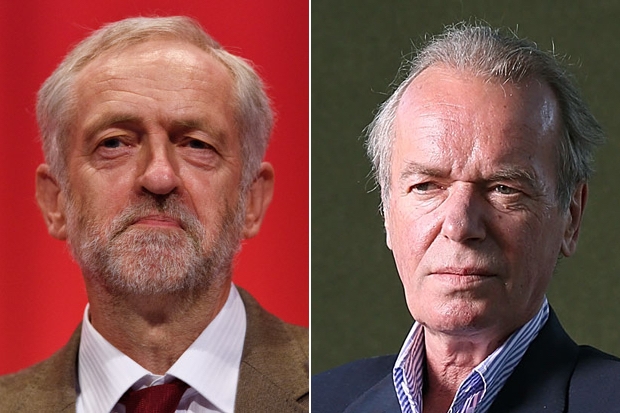

I worried about this when reading a lengthy piece eviscerating Corbyn in a newspaper for which I also work, the Sunday Times. It was written by Martin Amis — for me one of the most powerful novelists this country has produced since the second world war. Behind J.G. Ballard and David Storey, I would reckon, but probably ahead of Doris Lessing and Muriel Spark. He has not quite received the respect he deserves — from the awful prize-givers, the mimsy arts broadcasters, the literary hacks — perhaps for reasons of political correctness and one suspects that this grates upon the man, rightly enough. He is a far better novelist than his dad, I would suggest, and yet his dad hangs over him like a cackling black bat. Perhaps this is why he decided to stop writing novels which were primarily ‘funny’ and instead got very earnest indeed, not always to good effect. Still, we should not carp when a talented writer tackles such subjects as the possible nuclear Armageddon and the Holocaust, even if his marks on both subjects (à la Kurt Vonnegut, who retrospectively gave his novels university essay grades) are, respectively, C- and B+. That is what the best writers are there for — to deal with the big.

But I mean Amis as a novelist, not as a journalist. He once said that of all the literary pursuits, journalism was easily the easiest; odd, then, that he is not very good at it. His attack upon Corbyn began with a lengthy, hugely boring and ineffective trope about a cartoon cat, which may have lost many readers and almost lost me, a fan of the chap. The rest of it contained interesting and perceptive reminiscences of his time at the New Statesman in the late 1970s, where every other person was an ‘Identikit Corbyn’ and, as he puts it, ‘weedy, nervy and thrifty’, and the sensible people avoided them like the plague. The central attack on Jezza, though, was this: he is humourless (yes, tick: but I wonder how many other Amis fans thought a little wistfully that the same could not have been said about the younger Martin Amis), that he is possessed of a ‘slow-minded rigidity’ (yes, two ticks. Exactly the point) and — wait for it — that he is ‘under-educated’.

And it is this last barb which is the problem. However louche and hip Amis may once have been, or still mistakenly thinks himself to be, he is a fastidious snob, and every bit as estranged from the average voter as Corbyn himself (not least as a consequence of living in New York, of course). Amis’s novels, right from the very first, betray a terror of, and a distance from, the working class; for Amis the plebs are epitomised by the venal and thuggish and stupid shop steward Stanley Veale, or the dart-obsessed Brobdingnagian Keith Talent, from London Fields. Or the whole heap of them who populate his more recent novel Lionel Asbo — which was actually better than the critics decreed and contained certain elements of that long–forgotten thing with Amis, humour. These characters are signifiers of a class which is base in its aspirations, unable to tell a hawk from a handsaw, or indeed tell you where that quote came from, and they are threatening to take over. The plebs, the untermensch, the workers.

He is not so very far from Corbyn, then, after all. The same disdain for a vast group of people, for their uncouth views and their lowbrow culture and their neanderthal political sensibilities. An echo of Orwell’s patrician dismissal of the working class in Nineteen Eighty-Four: ‘Until they become conscious they will never rebel, and until after they have rebelled they cannot become conscious.’ A moronic agglomeration of plumbers and roadsweepers and sparkies and terrifying chaps on building sites, all brain-dead to the world.

Too much, already. We should be pleased that one of our greatest novelists deigns to involve himself in politics, and delighted that a national newspaper deems this deigning worthy of publication. My suspicion is that in its upper-class snobbery, it will have flung another bunch of voters Jezza’s way.

Lordy, we don’t want that.

Comments