Laura Cumming writes about art with a painter’s precision. She’s been the chief art critic for the Observer since 1999. Her fourth work of non-fiction, Thunderclap, is a beautifully illustrated memoir that intertwines biography, visual analysis and personal reflection. An eloquent homage to her artist father, James Cumming, and to the artists of the Dutch golden age, it explores the power of pictures in life and in death.

Dutch art is less about things and the way they look, and more about feeling, mood, charisma

Dutch art is a culture like no other, writes Cumming. ‘Which other nation wanted to portray all of itself in this way, its food and drink and physical conditions, its lovers, its doctors, housewives and drunks?’ Freed from Spanish Catholic rule after 80 years of warfare, the newly independent Dutch Republic emerged in the mid-17th century with a cultural boom: between 1.3 and 1.4 million paintings were produced by up to 700 painters in under two decades. Why then, Cumming asks, is so much of the art ‘seen but overlooked’?

‘That old cliché’ – as she calls it – about Dutch artists only ever replicating what’s in front of their eyes doesn’t help. The relegation of still life to an inferior art form – ‘just depictions of trivial stuff’ – hits hardest at 17th-century Dutch art because there’s so much of it. She’s heard curators disparage Dutch painting as ‘a brown art of cattle, cartwheels and mud, of peasants and platters, too many flowers and wide skies’. Too many perhaps for some, but not for Cumming: ‘I cannot get enough of Dutch art.’

Her passion is inherited from her Scottish father, a painter of semi-figurative art who in the 1960s was given a grant to study Dutch pictures and to visit the Rijksmuseum and Rembrandt’s house. It was the one and only holiday the family took abroad, and everything stands out in Cumming’s memory ‘like a comet’: the gable façades and cheese roundels, the bright bicycles and little bridges. For her, Dutch art is less about things, and the way they look, and more about feeling, mood, charisma: ‘a mysterious kind of beauty, a strangeness to arouse and disturb, an infinite and fathomless world’.

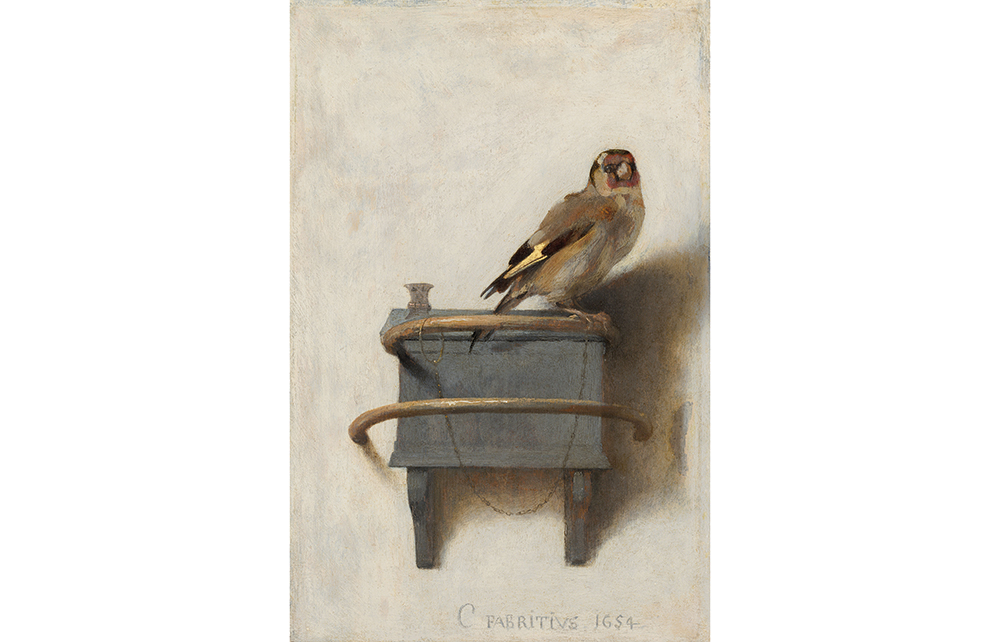

Chief among her cohort of artists is Carel Fabritius, best known for ‘The Goldfinch’ (1654), a charming small painting of a pet bird which found fame first in the writing of the 19th-century French journalist and art collector Théophile Thoré-Bürger and later in the bestselling novel of the same name by Donna Tartt. There are scant records about Fabritius’s life, cut short by the gunpowder explosion in Delft on 12 October 1654. Just a dozen of his paintings survive, and few display ‘a definitive subject or style’. ‘He could not be discerned in the throng, perhaps. Or, to put it more positively, he cannot be pinned down,’ writes Cumming.

In Thunderclap, she takes Fabritius – an artist ‘explained away’ by historians as the missing link between Rembrandt, with whom he trained in Amsterdam, and Vermeer, his neighbour in Delft – and makes a compelling case for him being ‘one of the greatest innovators in Dutch art’. Her quest to gather together the scraps of his life and art coexists with her desire to get to know the man her father was before she was born. ‘All of my ideas of life and art come originally from our conversations,’ she writes, though the first 40 years of his life remain a mystery. She wants to understand what both men saw, to delve deeper into their ‘unknown picture world’.

Cumming is at her strongest when translating what she sees in art into words. In her hands, a lute shines ‘like a new chestnut freed from the husk’, while a woman’s hair is ‘scraped back in a topknot too foolish for her intelligent face’. Blackcurrants roll towards the edge of a shelf ‘in a darkening tide’, and a pair of fresh peaches are ‘lunar fruit, marked like the seas and mountains of the moon’. Of two striped snails, she writes: ‘One is sulking in its shell, the other exiting stage left as if they’ve had a row.’

Alongside Fabritius is the great Amsterdam flower painter Rachel Ruysch, and Clara Peeters, who made magic out of humble foodstuffs. The intimate images of Gerard ter Borch precede the dazzling domestic scenes of Vermeer. Cumming came across the work of Adriaen Coorte by chance as a student and continues to marvel at his refined and original still lifes, which render each element in such astonishing close-up that ‘you feel the artist’s presence’.

Fabritius and Cumming’s father were born 300 years apart, in 1622 and 1922. Fabritius died, aged 32, in the explosion, James Cumming from cancer in his sixties. Cumming examines their art and celebrates the power of pictures to bring us closer, not just to other people but to other worlds. ‘Looking is everything,’ she writes. ‘And art increases this looking, gives you other eyes to see with, other ways of seeing, other visions of existence.’

Comments