A new biography of ‘Papa’ has deeply impressed Sam Leith, although its thoroughness — like its subject — ‘teeters on nuts’

Hemingway’s Boat is just what it sounds like. It takes as its conceit — and it’s a good one — that writing about Hemingway’s boat Pilar (now up on blocks in Cuba) is a way of getting at deep things about the man. Pilar was there all the second half of his life and may have been the only friend he never fell out with. Fishing was more than a recreation for Hemingway: it was at the centre, this book plausibly suggests, of his being in the world.

Paul Hendrickson duly set about getting to the core of Hemingway’s relationship with Pilar. And how! His research is flat-out phenomenal. It teeters on nuts. The author hasn’t just interviewed Hemingway’s sons and Hemingway’s surviving former helpmeets and friends. He has researched the history of the company that built Hemingway’s boat, and he has visited the muddy waterway in which she would first have floated. If a journalist published a hack news report on Hemingway’s arrival in Cuba, Hendrickson will have researched his subsequent career. If Hemingway fished a particular stream in Michigan on one occasion in his teens, Hendrickson won’t just have visited it: he’ll have fished it too. This is the total immersion school of — well, biography isn’t quite the word. It’s a sort of mental home invasion.

The narrative loops around in time — describing the acquisition of the boat (Hemingway begged his editor for a loan to buy it) and going forward and round and back to his childhood, zipping into his afterlife or legacy, and closing in, always, on his death. As well as the Pilar story, it describes a trio of others — the author’s three biggest scoops — arranged like a Venn diagram.

There’s Arnold Samuelson (‘Maestro’ or ‘the Mice’), a well-educated hobo who knocked on Hemingway’s door in search of advice and ended up crewing his boat; there’s Walter Houk, a junior diplomat in Havana, whose wife worked as Hemingway’s secretary and who was similarly taken up; and there’s Hemingway’s youngest son, Gregory (‘Gigi’). The author interviewed the latter two, and extensively researched the first, telling their stories fully and sympathetically in the hope that in the overlap at the centre of the Venn diagram we’d get somewhere close to ‘Papa’.

It works. This is, as promised, a book that finds much in Hemingway that has been generally overlooked and places you formidably deep in his world and his life both as a writer and as a man. It takes you down to the insertions and deletions in manuscripts, and shows you how the sentences were formed; with what agony and then excitement he wrote.

Not that Hendrickson stints on giving us the macho roister-doistering either. Hemingway was insanely competitive, and behaved with infantile petulance when a guest out-hunted or out-fished him. At one point the author remarks drily, apropos Hemingway shooting himself in the leg on board Pilar:

Perhaps if the fisherman hadn’t been trying to land the fish and gaff it and shoot it in the head all at once, the accident would never have occurred.

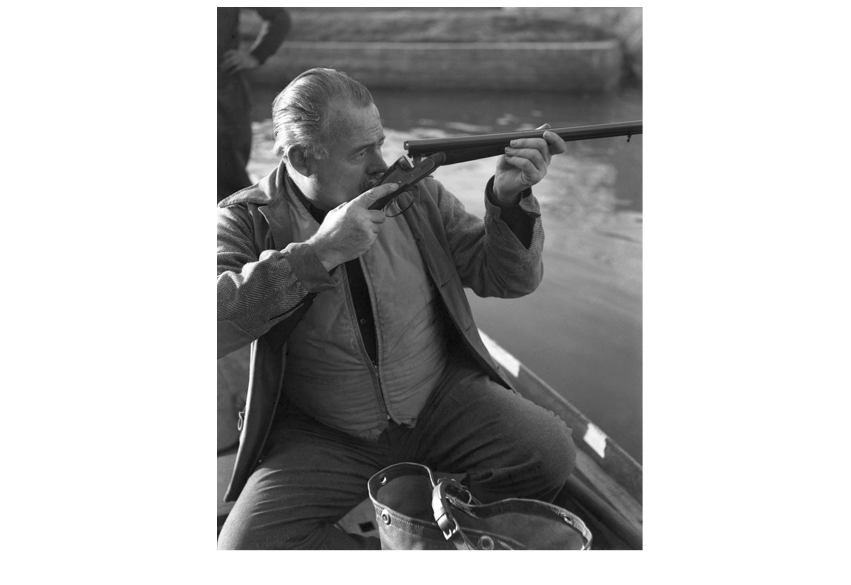

And he sure did love shooting stuff. Here we meet Hemingway shooting at beer bottles; Hemingway shooting his initials into the top of a shark’s head with a pistol;

Hemingway blowing away seabirds with a shotgun in a fury after Archibald MacLeish failed to heed his fishing advice (‘Ernest took to shooting terns, one on one barrel and the grieving mate on the other’); Hemingway shooting at sharks with a submachine gun; Hemingway shooting a toilet . . . .

When heavier ordnance and more challenging opponents did not present themselves, the great writer wasn’t above beating up a dead fish — and would

show up at the dock close to midnight in a jubilant drunk to find his 514-pound giant bluefin tuna that he’d fought for seven hours, and pound his fists over and over into the strung-up raw meat in the moonlight the way prizefighters in the gym slam at the heavy bag.

Anything we should talk about, Ernest, dear?

But here, too, is the Hemingway who knew what a monster he could be, and regretted it. This was a man who was capable of great acts of kindness — welcoming waifs and strays into his life, generous with money and time — and of remorse. There are some killingly poignant quotes — long, wonderful letters written to the sick children of friends, for instance, and the interviews with Hemingway’s beloved, ruined, cross-dressing Gigi. It gathers to a really moving end. There is so much in this long book that is new and interesting and enlightening; it seems to defy précis.

So I regret that, though awed by its range and depth and perceptiveness, I do have some reservations. Hemingway’s Boat chugs into harbour in the UK on a breaking wave of critical admiration not only for its research, but for its prose; it’s in a style that strikes some people, especially the author, as literary. To my mind it’s showily and irritatingly overwritten: filled with verbless sentences, cheap-tricksy switches into the present tense, crazy levels of descriptive detail and portentous turns of phrase, the odd one of which is gauchely repeated; at least three separate chapters contain, and two end with, the words: ‘Amid so much ruin, still the beauty.’

The problem is, he’s doing several things: this is not just a book about Hemingway, it’s also a memoir of writing a book about Hemingway, and it is in some ways — covertly, perhaps — a novelisation of the author’s worshipful and faintly competitive relationship with his literary master. ‘You’ — Hendrickson does love the second person singular — is sometimes Hemingway, sometimes the reader, sometimes Hendrickson.

He will not let a sentence pass without reminding one who’s in charge. He bosses one about (‘take another look at the photograph . . . drift your eye back to the image at the beginning of this chapter’). He interpolates his own voice even into quotations, and lets what he takes to be a Hemingway swagger drift into his prose (everything’s ‘goddamn’ this and ‘damn’ that) — but the book reads less like a tribute than an act of appropriation. The weirdest,strongest and most telling thing about this aspect is that the author writes about Hemingway using — which you almost never see in non-fiction — the free indirect style.

Someone has apparently told Hendrickson that this is literary writing, and that it will make the difference between a good book and an astonishing one. I don’t think Hemingway — who, as Hendrickson admits in passing, is much, much harder to imitate than he looks — would have agreed. This book would have been astonishing without it.

Comments