It wasn’t long ago that a Conservative government was congratulating itself for achieving the lowest unemployment figures in half a century. This won’t wash any more, since the wider picture has become clear: while official unemployment figures remain low, figures for ‘economic inactivity’ have seen a sharp rise. We have 9.4 million of working age who are economically inactive – a number that has increased by one million since before the pandemic. It is just that only a small proportion of them show up in the unemployment figures. Many of the remainder – 2.8 million – are on long-term sickness benefits, a number that has risen by 700,000 since the eve of the pandemic. As has been argued many times, including by the Bank of England, so long as we have so many people not working it is hard to see the economy returning to robust growth.

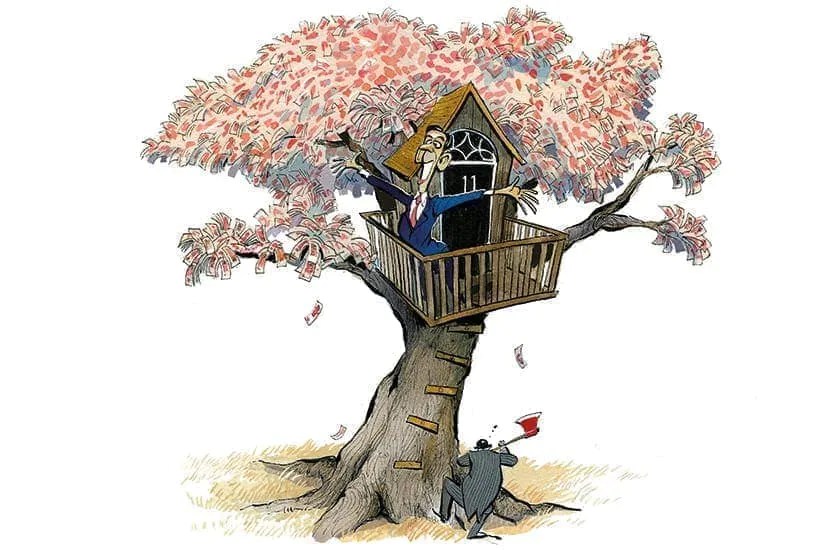

Economic inactivity seems to be a malaise that is connected to an excessively generous furlough scheme

But what is driving the rise in economic inactivity? In a report published today, the Centre for Social Justice (CSJ) offers a fresh insight. It compares the experience of Britain with Denmark, Sweden and Norway, which did not suffer such a sharp rise in economic inactivity after Covid, and where the labour market has recovered far more healthily. What did they do that was different? They used furlough schemes far more sparingly. They did not subsidise employers to preserve jobs. Moreover, a higher proportion of their workforces have vocational qualifications and fewer have academic qualifications. Lifelong learning is a stronger theme of their education systems, helping people to retrain for new forms of employment at any age. Finally, their welfare systems are more strict than ours, with greater use of sanctions against those who fail to seek work.

In other words, economic inactivity seems to be a malaise that is connected to an excessively generous furlough scheme and its after-effects. What is so remarkable about the rise in long-term sickness in Britain since the pandemic is that the majority of the rise – 500,000 of the 700,000 – has occurred since the beginning of 2022: a period after the pandemic had largely subsided. Long-term sickness seems to have been given a jolt just at the time when fewer people were falling ill to the disease, but when the furlough scheme was being dismantled. There is no data to show how many of the extra people on long-term sickness benefits were previously on furlough, but the timing of the rise does give credence to the argument that paying people to stay away from work for months on end appears to have made it difficult for them to return to work afterwards.

While highlighting the difference between the British and Scandinavian experiences of economic inactivity, the Centre for Social Justice goes on to propose a Dutch solution. The Netherlands, it argues, has succeeded in getting people back into work by devolving the welfare system to local government, resulting in better employment support and adult education. The CSJ also has kind words about a Work and Health programme pursued by Greater Manchester.

The CSJ, set up by Iain Duncan Smith, was a huge influence on the Conservatives’ welfare reforms from 2010 onwards, which promised to ‘make work pay’ by removing perverse incentives to stay on benefits, and which resulted in the creation of Universal Credit to replace a myriad of benefits. While those reforms may at first seem to have succeeded – the number of people on long-term sickness benefits fell between 2010 and 2019 – they seem to have been derailed by the pandemic. Understanding why is going to be an important part of reversing the upwards trend since then.

Comments