The impact had shattered the churchyard path. Chunks of asphalt and mortar lay in the surrounding grass. Just next to the path, like a broken chess piece, lay the remnants of the church’s 150-year-old spire. A few hours earlier, it had stood at the very top of the church, towering over the churchyard. Mercifully, the Victorian construction had fallen to earth rather than through the church roof. For reasons now lost, St Thomas’ in Wells is one of the very few English churches with a spire to the north-east corner.

The list of people one can call for such emergencies is not long. In the event it was 37-year-old James Preston who picked up the phone. Preston is a stonemason and steeplejack whose work has seen him dangle from almost all the historic buildings you’d find in the Ladybird Book of English History: Buckingham Palace, Windsor Castle, Stonehenge, Longleat, the Radcliffe Camera and Whitby Abbey, to name but a few.

The spire’s fall, captured on video by a neighbour, took place at the height of Storm Eunice in February. When I meet Preston six months later, he shows me the workshop where the new spire is being made and takes me to St Thomas’ church itself. A 20-mile drive intervenes, and Preston – stubbled and tanned – tells me about the various stone varieties of the West Country. Geologically speaking, we’re at the bottom of a band of oolitic limestone that curves, via Oxford and Bath, all the way up to York, formed during the Jurassic period when much of the Cotswolds was under tropical seas. Look closely at the fine Georgian townhouses in Bath or the little Gloucestershire weavers’ cottages and you’ll see ancient shells and the fossilised remains of ancestral starfish. Bath stone is ‘a soft oolitic limestone’ – ‘oolitic’ meaning ‘egg stone’, referring to the spherical grains of which it is composed – ‘but then we’ve got Hamstone, and Doulting stone, and then you get rubbles. Historic buildings in this kind of area are generally soft limestone, with Bath stone features and maybe Lias rubble walling,’ says Preston.

Limestone is soft, crumbly and warm-hued, quite unlike the more austere Portland stone, to which we owe much of central London. Casual viewers can spot these types of stone, but Preston has a connoisseur’s eye. As we approach Wells, he points out buildings made with Doulting stone, the kind of which St Thomas’ is made. ‘Doulting is an oolitic limestone,’ says Preston, ‘but it’s more orange, and it’s coarser.’

He describes the different mortars used across Britain. They once varied according to local geology, then became brutally standardised in the postwar period, causing damp in buildings where impermeable mortar sealed in moisture. Preston and his colleagues pay close attention to the original mortars, disaggregating them so they can work out their ingredients en route to imitating them. ‘If you go around London, you can find buildings with tiny white [mortar] joints. You go somewhere else, and they’ll be pink, made up of pink sands, or red.’

Preston sees architectural subtleties where other humans would not. ‘I’ve been doing it for a long time,’ he says. He’s been working in the field since he was 16, when he left school to join the same firm he works for two decades later.

What kind of 16-year-old leaves school to become a stonemason? ‘I don’t know!’ he says. ‘It’s weird.’ School, he explains, ‘wasn’t really for me. I’m not a not-academic person, but I’m not really a sit-down classroom-learning type. I’ve always been practical with my hands, mending things and wanting to do things by hand.’

He found he enjoyed the geometry of masonry and its demand for precision. Put through college as an apprentice with Sally Strachey Historic Conservation (he still works for the company, known as SSHC, today), he learned to carve humans and animals, and also to cut a block of stone with an accuracy of one millimetre. This discipline is called banker masonry. ‘The tolerance is one millimetre in one direction, because if you’re still too high, you can take it down. Whereas if you’ve gone too low, there’s nothing you can do about it.’

Preston’s skill as a stonemason neatly dovetailed with another skill of his: climbing. As a teenager, he’d been a hobby climber; in his twenties, working at Farleigh Hungerford Castle for SSHC, he realised that the team had left a blanket at the top of a high wall. Rather than set up the scaffolding again, Preston used ropes to make the climb himself. His career as a modern-day steeplejack had begun – a career that has since led him to abseil down Buckingham Palace and to climb towers and spires otherwise untouched by human hands.

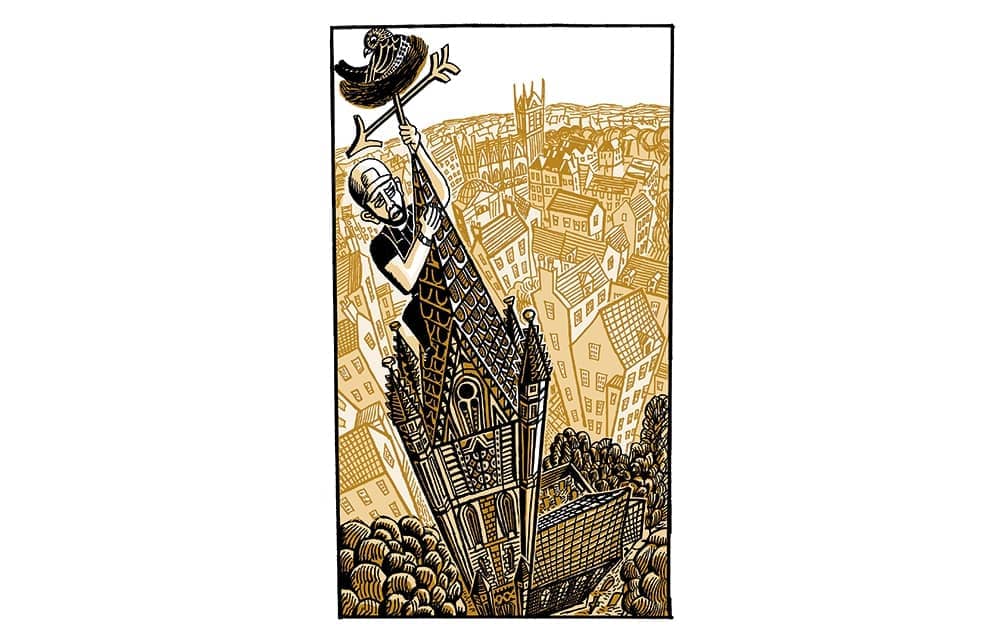

Done with care, he says, rope climbing is safer than working from a scaffold. But it’s still thrilling. ‘I love climbing church spires,’ he says. ‘As you progress up a church spire, the mass of what you’re climbing becomes smaller and smaller, and so you’re more and more exposed as you get up. It reduces up to nothing, and it never ceases to be exciting.’

And then there’s the reward at the top. ‘The views are something you can’t match, and very few people will have seen them. Climbing spires is the best thing, for sure, about working in rope access, or working in historic buildings.’ His favourite view is from Wakefield Cathedral, which has the tallest spire in Yorkshire.

Preston turns his van into a country lane, and we arrive at the workshop. It’s a converted farm building, open to the elements. Outside it stand two spires: the old one, which is grey, weathered and pieced together from lichen-coloured rubble; and the new one, which is sleek and cream-coloured. (It’s Doulting stone, Preston says; my unsophisticated eye does not detect much orange, but he says different beds of the same stone can come in different colours.)

As an apprentice, Preston learned to cut a block of stone with an accuracy of one millimetre

Preston had to piece together the old one, having taken its constituent chunks back to the yard, in order to work out the dimensions for its replacement. ‘We spent a couple of days just sticking bits of stone back together to try to work out what it’s supposed to look like,’ he says, as we inspect the two spires in the sunshine.

Between the spire and the weathervane will be placed an ornamental component: a finial stone. Its three-dimensional floral form was carved by Preston, faithful to the shattered original, over four days. It’s standing on a workbench today, ready for its one-way trip to St Thomas’.

Before we leave, Preston shows me the yard-long steel bolt that, in the mid-1990s, had been implanted into the spire. The intention was to keep the spire secure, but the engineers hadn’t reckoned for wind speeds as high as those brought by Eunice. The bolt, thick as an exhaust pipe, has been bent into a C-shape by the force of the fall. Preston and his team will have to leave a more durable spire than the one they found, which they will do thanks in part to a better-designed stainless-steel tie-down rod. ‘We never intend to have to redo work in our lifetimes,’ he says.

On our way to St Thomas’, we drive past Wells Cathedral, another of Preston’s former projects with his team at SSHC. Above the famous astronomical clock on the north transept are several subtly cleaner panels of stone, put there by Preston and his team.

Stonemasons like to grumble about their industry. They cite the poor pay, the long drives, the contrast between the harried contractors and the unhurried in-house cathedral masons, of whom there are still a few groups. Despite his job’s shortcomings, though, Preston counts himself as privileged. On cathedral roofs, he sees grotesques put there for God’s amusement and nobody else’s; and seeing him climbing up spires like some sort of action figure delights and thrills his five-year-old son, Blake. ‘I think we’re lucky,’ he says. ‘I really do.’

There will always be plenty of work. The misguided postwar mortaring keeps stonemasons busy. Old buildings cope well with high temperatures, but if the Met Office is correct in its prediction that climate change will cause a higher frequency of wind storms, then the damage caused by Storm Eunice will be repeated several times this century.

We’re sitting on the low wall that borders St Thomas’ churchyard. With my hands resting on the wall’s top edge, I can feel the crumbling Doulting stone of which it’s made. We crane our necks to see the decapitated spire. Some time in the coming weeks – SSHC keeps the precise date quiet, lest spectators distract the climbers – Preston and his workmen will install the new spire.

They will do it with the help of a large crane, and they will just have to hope that their modern methods last the centuries. As Preston muses in the workshop, in 200 years’ time stonemasons might curse their forebears (‘21st-century idiots’) who went round putting stainless steel into our ancient buildings.

Comments