My heart is pounding, my hands are shaking and there’s a leaden feeling in the pit of my stomach. My pupils are dilated and my digestive process has ground to a halt. My sympathetic nervous system is kicking in and activating its ‘fight or flight’ response. And how do I know all this? Because the subject of ‘Stress, and the Body’s Reaction to It’ is one of the topics on the AQA AS-level psychology syllabus — an exam I’m just about to sit. Stress? I don’t just know about it. I’m living it.

Three decades after I last took an exam, I am standing outside the sports hall of my local sixth-form college with five other adults and several hundred 17-year-olds preparing to submit ourselves to everything the question setters can throw at us. I have not felt this scared since Uncle Jack showed his true colours in the final series of Breaking Bad.

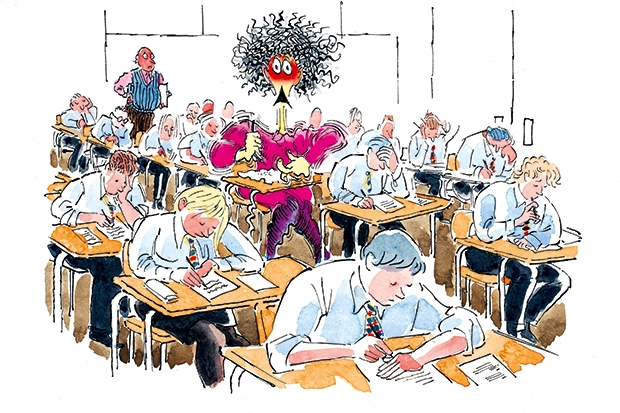

A voice in the queue mentions that there are only 15 marks between an A grade and a D. Worried faces do the maths. If we mess up the mighty 12-mark essay question (will we remember the difference between ‘discuss’ and ‘describe’ and ‘evaluate’?) and miss the point of a couple of two-markers, we are sunk. Our grades will plunge from here to ignominy, regardless of how much psychology we know. The doors of the hall swing open and the stampede for desks begins. Mine is wobbly and bears the usual legends: ‘Sod Off’, and ‘So-and-So Is a Such-and-Such Obscenity’. Invigilators patrol the aisles, checking our see-through pencil cases for evidence of cheat sheets and scrutinising our photo IDs (yes, really): driving licences and passports for the golden oldies, student cards for the rest.

As the clock ticks towards zero hour, a recorded voice reminds us that this is our last chance to hand in our mobile phones, that we must write in black ink and that we are now under exam conditions. Everyone’s sympathetic nervous system is in overdrive. The lad at the desk next to me has the corner of his question paper booklet already clasped in a shaking hand, ready to fling it open the second the signal is given.

And now that moment has come. A lady in a flowery dress tells us in a severe voice: ‘You may now turn over your exam papers.’ The words swim in front of me. We must answer all the questions, around 30 of them in total. There is no choice. There is no coursework on this syllabus to give us a cushion. Hang on, didn’t somebody say that exams had got easier? The knowledge drains from my brain at the speed of vegetable water through a colander. What were those mnemonics again? FLUB? UDOPI? SCAART? I can’t even remember what they are, let alone what they stand for.

The boy next to me seems to have belted through his paper at breakneck speed and is now slumped in his chair, legs outstretched, arms limp by his side. This will be his default stance for the remainder of our ordeal, although he will occasionally lean forward to scribble a sentence or, at one point, to bang his head three times on his desk.

I know exactly where he is coming from. The minutes tick by and I feel myself falling into all the traps. I’m not stopping to read the question properly. I’m not understanding what the examiners are getting at. I’m writing too much for the short answers and too little for the long ones. Worst of all, I’m not sticking to the printed lines they give you to write on but scribbling wildly all over the place. It’s only after the exam is over that I learn this might well have cost me points, if the clever high-tech marking system can’t decipher my words. Who knew?

But that’s for later. For now, it’s time to stop. We must put down our black pens. We must not finish our sentence (and boy, does it feel like one). We must remain silent until our papers have been collected and we’ve been told we can leave the hall.

Wordlessly, an invigilator points at our row and beckons in the manner of a police officer directing traffic round a pranged car. We clump outside. Our gang huddles by the door, comparing notes. What did you put for that multiple choice question? C or B? Damn. I put that and crossed it out and put the other one.

The teenagers disperse to do whatever they do after exams. They seem to think it went OK. Only the adults, for whom the result doesn’t matter, are visibly anxious. Although we have all of us held down jobs for years and most of us have qualifications in other things (our number includes a florist, a mental-health nurse, a lawyer, a history teacher and a hospital data analyst) we are all over the place when it comes to AS-level psychology. We cross the road for peach bellinis at a nearby pizza place. Gradually we return to our grown-up personas.

And so that’s it — until the dreaded results day arrives in the middle of August, by which time I have long forgotten the case studies I so painstakingly committed to memory. But there’s something I have learnt from the whole experience, and it’s this. That exams, when so much is riding on them, are really, really scary. That every parent and teacher should take one to remind themselves how nerve-racking it can be. That the pressure on our children to attain a particular grade is intense, and horrible, and relentless. And that it can all go wrong for them in the blink of an eye: a misread question here; a loss of concentration there; an unhappily altered ‘relationship status’; a missed alarm or bus.

Even the January retake safety net has vanished, a casualty of the previous government’s well-intentioned, but often brutal, reconfiguration of the exam system. I’d always felt somehow doubtful about the merits of such a one-strike-and-you’re-out decree — after all, if nobody ever had a second crack at anything, would there be any drivers on the road? Would anybody have a job? Whatever happened to that excellent maxim ‘if at first you don’t succeed, try, try again’?

And now that I’ve walked in their shoes, albeit for only a short distance, I feel ever more sympathy for my young co-examinees. For me, that AS-level was a bit of fun. For them, it could shape their futures.

I’ve often in recent months recalled a story told to me by a now long-deceased news editor about his application for his first job on a local paper. He was asked just one question: ‘Can you ride a bike?’ These days you need to be able to walk on water to get into the media, as well as being in possession of a clutch of A-stars, firsts and relevant internships.

So parents, take a tip from me, if you will. Please, never again ask your children how it went, whether they left any gaps and whether they gave themselves enough time to go back and check their answers. I wouldn’t have wanted to answer those questions post-exam, and neither do they. And don’t be too angry with them if everything goes horribly wrong. It might, actually, be nothing to do with whether they did enough work or not.

And to those teenagers all around me that day, I really hope it went well for you. I hope you got the grades you needed and are about to start the courses you aspired to. Because if the whole thing was anything like as stress-inducing for you as it was for me, you deserve it.

Katherine Whitbourn got an A.

Comments