I suspect Adam LeBor and his publishers must have struggled to come up with the title The Last Days of Budapest: Spies, Nazis, Rescuers and Resistance, 1940-1945. The book certainly does what it says on the cover, but its pages contain other Magyar-themed subjects. We are offered a wide-ranging reflection on Hungary in the first half of the 20th century, from the harsh measures of the 1920 Trianon treaty to the devastating arrival of the Soviet army in Budapest in 1944.

LeBor switches between an Olympian view of European geopolitics, trawling diplomatic archives and political memoirs and focusing on individuals – Hungarian aristocrats, Zionists and nightclub singers – to show how history felt on the ground. He is particularly concerned with the fate of Hungarian Jewry.

By 1945, it was total anarchy, total brutality: murder, rape and starvation

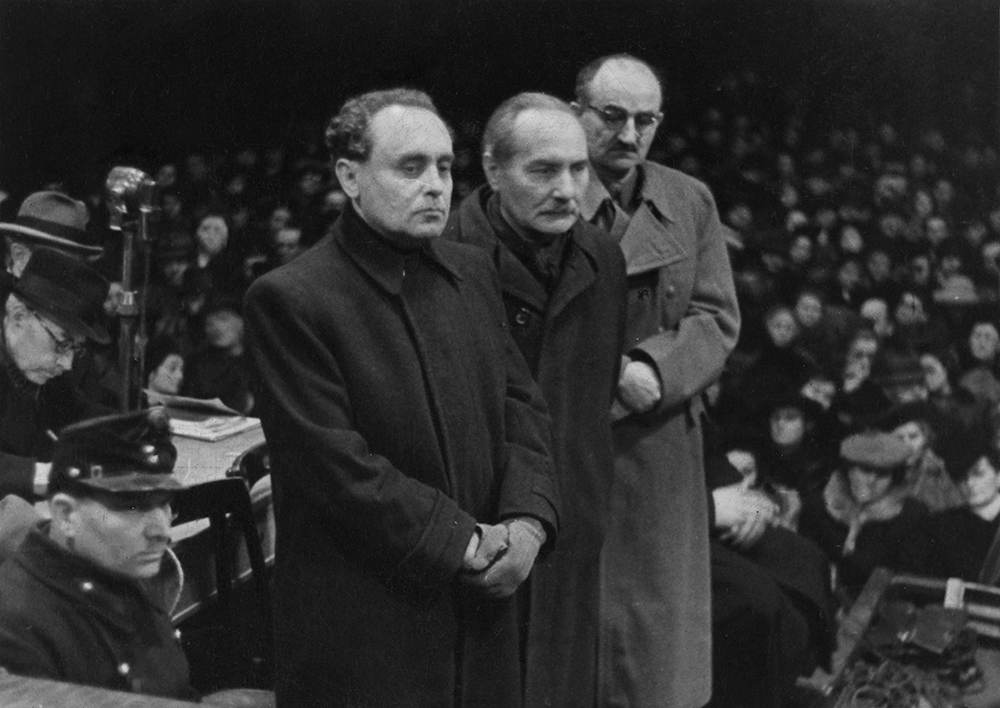

The central figure in this period of Hungarian history is Admiral Miklos Horthy, the regent. Those who know little about Hungarian history tend to lump him in with the fascist dictators of the era; but Horthy wasn’t a fascist (he banned the Nazis) and he wasn’t a dictator. He was a figure who seemed to have wandered out of an operetta, an admiral without a navy, a regent without a king, who exercised undemocratic power but who presided over a parliamentary democracy.

LeBor, a longtime Budapest resident, is too knowledgeable to make that mistake; and there’s no doubt that the report card standard ‘could have done better’ applies to Horthy, like most leaders. But even historians who give Horthy a break on the fascism front tend to focus on the poverty and racism of Hungary in the 1920s and 1930s (as if those phenomena were unknown in the US, Britain or elsewhere in Europe at the time). Hungary’s anti-Jewish law of 1920, the Numerus Clausus, which limited the intake of Jewish university students is often cited, although this percentage-of-the-population representation is exactly the sort of policy that current DEI zealots are espousing.

Horthy was a reactionary, who thought the British Empire was rather well run, and an anti-Semite in that he wouldn’t have liked his children to marry anyone Jewish (although it should be remembered that there were Jewish families who wouldn’t have wanted their children to marry Horthys) but who had Jewish friends. He was also, in the best sense of the term, an officer and a gentleman.

His coming to power, after Bela Kun’s Hungarian Soviet Republic, was followed by the White Terror, in which many Jews, who often had nothing to do with the Bolsheviks, were tortured and killed by Horthy’s supporters, despite his efforts to rein them in. The White Terror’s body count was indeed higher than Bela Kun’s – but then Kun only had 133 days to get liquidating.

Keeping the pro-Nazi nutters in check was one of Horthy’s main concerns, but he had limited success. The prime minister Gyula Gombos, who coined the term ‘Axis’ powers, died in 1936; but there were many others in ministries and the army who felt that Hitler, or at least Germany, was the way to go.

Hungary was in a difficult position when the second world war broke out. Traditionally friendly with Poland, Hungarians helped fleeing Poles, despite German outrage. Later, Allied POWs enjoyed unusual freedom, some French prisoners even working as waiters. LeBor skilfully depicts the war years in Budapest when politicians, diplomats and spies were all playing a role, bluffing. The Germans knew what the Hungarians were doing, and the Hungarians knew they knew. (Spies seem to love spying on other spies more than anything else.)

The war years also exemplified the human fondness for wishful thinking. Horthy hoped he could somehow extricate his country from the conflict, or at least curtail German excesses. The Germans hoped they could get the Hungarians to do their bidding without a messy invasion. The Jews hoped things wouldn’t get worse. Everyone ended up bitterly disappointed – even Adolf Eichmann. Some of the SOE operations that LeBor has investigated would make a good comedy; others not. Overall, they scored nul points in Hungary because they too succumbed to wishful thinking.

The final chapters dealing with the Holocaust, the trains to Auschwitz, the Arrow Cross massacres – when Jews were shot on the banks of the Danube by teenage fascists – and the wholesale carnage of the siege of Budapest as Germans, Hungarians and Soviets battled it out, are inevitably chilling. It was total anarchy, total brutality: murder, rape and starvation. You didn’t want to be there. The story of the Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg, who saved thousands of Jews, is well covered; but Wallenberg had some protection as a diplomat, although that status didn’t save him in the end. More amazing was how ordinary Hungarians risked their lives by hiding Jews in their pantries and cellars.

If you have the stomach to read yet more about the war years, Bela Zsolt’s memoir on the Hungarian Holocaust, Nine Suitcases, is the bleakest book I’ve ever read and really should come with a health warning. On the fiction side, there is Sandor Marai’s Liberation, by far his darkest work, soon to be available in English. Written just after the war, it was only published in Hungary in 2000, long after the author’s death, presumably because no one wanted to be reminded about 1944.

Comments