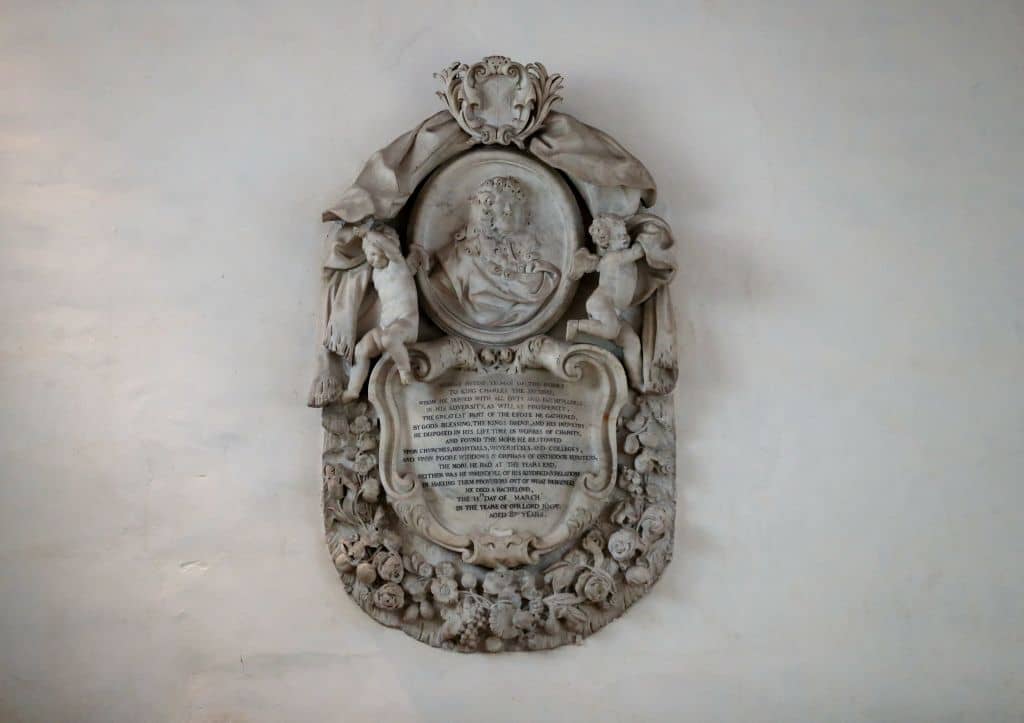

An event took place in Cambridge last week that was rare enough to reach the national press: a public hearing by the Diocese of Ely Consistorial Court in Jesus College chapel. It was brought about by a group of alumni who were opposing a move by the Master and Fellows of the College to remove a commemorative plaque to one of their greatest benefactors, the 17th century courtier and financier Tobias Rustat. His financial bequest was equivalent to over £4 million in present values, and his munificence is – or rather, was – celebrated in an annual College feast.

I attended much of the hearing, spread over three days. It was calm, exquisitely courteous, decorous in wigs and gowns, and occasionally enlivened by the sort of ponderous legal repartee that readers of Rumpole of the Bailey would have savoured. Both sides presented their arguments in detail, with care, and at considerable length. Some might have thought it much ado (and much expense) about nothing. But as the hearing proceeded the points at issue, which at first sight appear arcane, became increasingly clear and significant. Sometimes embarrassingly so.

Undeniably the College have a substantial case, which revolves round one simple point. Rustat was an investor in a slave trading company. For that reason, his memorial – a unique and artistically important three-and-a-half ton marble carving from the workshop of Grinling Gibbons – is now offensive to students, Fellows and not least the Master, Sonita Alleyne (the first black female head of a Cambridge college). They want it gone. They are supported by the Bishop of Ely himself, the Rt Revd Stephen Conway, and the Dean and Chaplain of the College. The case is now to be determined by the Deputy Chancellor of the diocese, sitting as judge.

Perhaps the College will get their way. But I do not think they emerge from the process with credit. So convinced were they of their moral probity and intellectual self-sufficiency that they were not really interested in anyone else’s opinion or expertise. Having made up their collective mind, they were not inclined to confuse it by facts. Alumni who wrote reasoned counter-arguments (including a distinguished black academic) or offered detailed information about the sources of Rustat’s fortune, were ignored or brushed off. Requests for information about the College’s own research into the subject were denied on a variety of pretexts.

Looming behind all this is the grubby question of double standards

Was Rustat truly a ‘slave trader’? Was his fortune derived from the trade? Did any of the money he gave to the College come from trading in human beings? That last possibility, said one witness, was ‘vanishingly small’.

What about the rest of his long and respectable life? Was it all tarnished by his investments in the Royal African Company, and association with a trade that was then almost universal? Were the emotions expressed by some students whipped up by misinformation circulated by the College itself? Should students not be informed of the complexities of the issue, rather than being fed what one of them called ‘inflammatory language’?

Such considerations were swept aside by the College. Was the Master not concerned, she was asked, that students who had written to support the removal of the memorial had used identical phraseology, and that this phraseology was fallacious? It didn’t appear so. ‘I’m talking as a person of colour with lived experience’, Sonita Alleyne told the hearing.

When Professor Lawrence Goldman, speaking as an opposing alumnus, mildly suggested she was not the only person with such lived experience (he is Jewish), she replied that this was not at all the same thing. A Whoopi Goldberg moment? Anyway, as the College’s barrister put it, any association with slavery, however slight, was ‘sufficient of itself’ to make a memorial ‘problematic’, if not ‘an abomination’. If this is accepted as a precedent, ecclesiastical lawyers may look forward to much profitable employment.

Behind the sometimes tedious legal pedantry lie several significant issues. One, as the Bishop of Ely put it with admirable directness, is ‘who owns our history?’ For him and Jesus College, the answer seems clear: those who can stake the loudest claim to victimhood – in this case, some Cambridge students and academics who to most people lead highly privileged lives. Thus is decided, in the words of the Bishop (who is chair of the Church of England’s National Board of Education), what is suitable for ‘celebration’ in our history. This in a nutshell is what our present culture wars are about. They who control the past control the future.

Another issue is what university education, including religious education, should involve. Should it provide reassurance, a safe space in which students are not expected to face uncomfortable views? Or should it confront them with moral and intellectual complexities, and encourage them to examine their own presuppositions? Cambridge students, said the Master, would not accept the latter, nor should they: the Chapel should be ‘an uncontested space’ which students ‘look at with the morality they have now.’ To this, Professor Goldman, an Oxford historian with many years of teaching students, responded that the College pleaded the priority of ‘pastoral care’, but that the real failing of pastoral care was not to educate.

Looming behind all this is the grubby question of double standards. As is now well known, Jesus College has a close relationship with the People’s Republic of China, from which it has received substantial funds. If Rustat’s money was ‘tainted’, is not this money tainted too? If 17th century slavery was an abomination, what about 21st century slavery in China?

Dr Véronique Mottier, chair of the College’s legacy of slavery working party pleaded ignorance on this. ‘I’m not an expert,’ she said. As it happens, she is not an expert on 17th century slavery either, being a social scientist specialising in theory, gender and sexuality – adequate, apparently, for judging Tobias Rustat, though not for judging Xi Jinping.

How much money had the College received from China? ‘Ask the Master’, replied Dr Mottier. The barrister duly did, and the Master replied that the College had an ethics committee and followed University policy. This was not a reassuring answer. When asked whether she would denounce human rights abuses today with the same energy as those three centuries ago, she ventured that violations in China ‘should concern us’.

But all this, declared the College’s barrister impatiently, was ‘tilting at windmills’. The issue was a very narrow one: moving a commemorative plaque. Talk of cancel culture, tainted money and relations with China were a ‘complete irrelevance’. So there we have it. The College hopes to win its case by excluding wider ethical considerations. If I were a member of Jesus College, I would not be feeling very proud. ‘Hypocrisy is not a Christian virtue,’ observed the opposing barrister in his closing remarks. Many eminent authorities seem to disagree.

Comments