In italics at the very end of the preface to Slouching Towards Bethlehem (1968), Joan Didion spills the beans: ‘Writers are always selling somebody out.’ It’s hard to improve on that, but we can at least specify that she had journalists in mind, not poets or novelists, though probably she looked on all scribblers with a cold eye. Six years later, Didion’s husband John Gregory Dunne published Vegas: A Memoir of a Dark Season, which isn’t really a memoir, more a queasily auto-biographical novel. Or, as he puts it, ‘a fiction which recalls a time both real and imagined’. A time and also a place – Las Vegas, Nevada, in the early 1970s.

Vegas is ‘an idiot Disneyland of celestial hamburger stands and gimcrackery fairy palaces’

The Didion-Dunne marriage is the shadowy backdrop. He’s having a ‘nervous breakdown’ – a phrase you don’t hear much any more. He tells her that ‘living with her was like living with one piranha fish’. She says he’s ‘clinically detached’. His idea of therapy is to do some reporting, which ‘anaesthetises one’s own problems’. He hopes to achieve ‘absolution through voyeurism’.

And so on to Las Vegas, where he rents a flat in an apartment block called the Royal Polynesian. Over the next few months he gets to know some quintessential Vegas characters: a hooker, a stand-up comic and a low-rent detective. He earns their trust, conscious that he will violate it. With her customary acuity his wife tells him that he’s in Sin City to ‘vandalise other people’s lives’ instead of coming to grips with his own. In other words, writers are always selling somebody out.

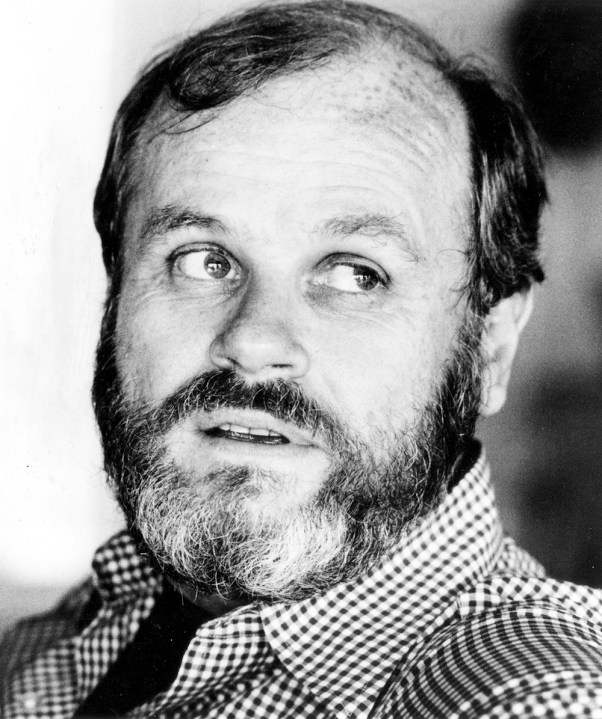

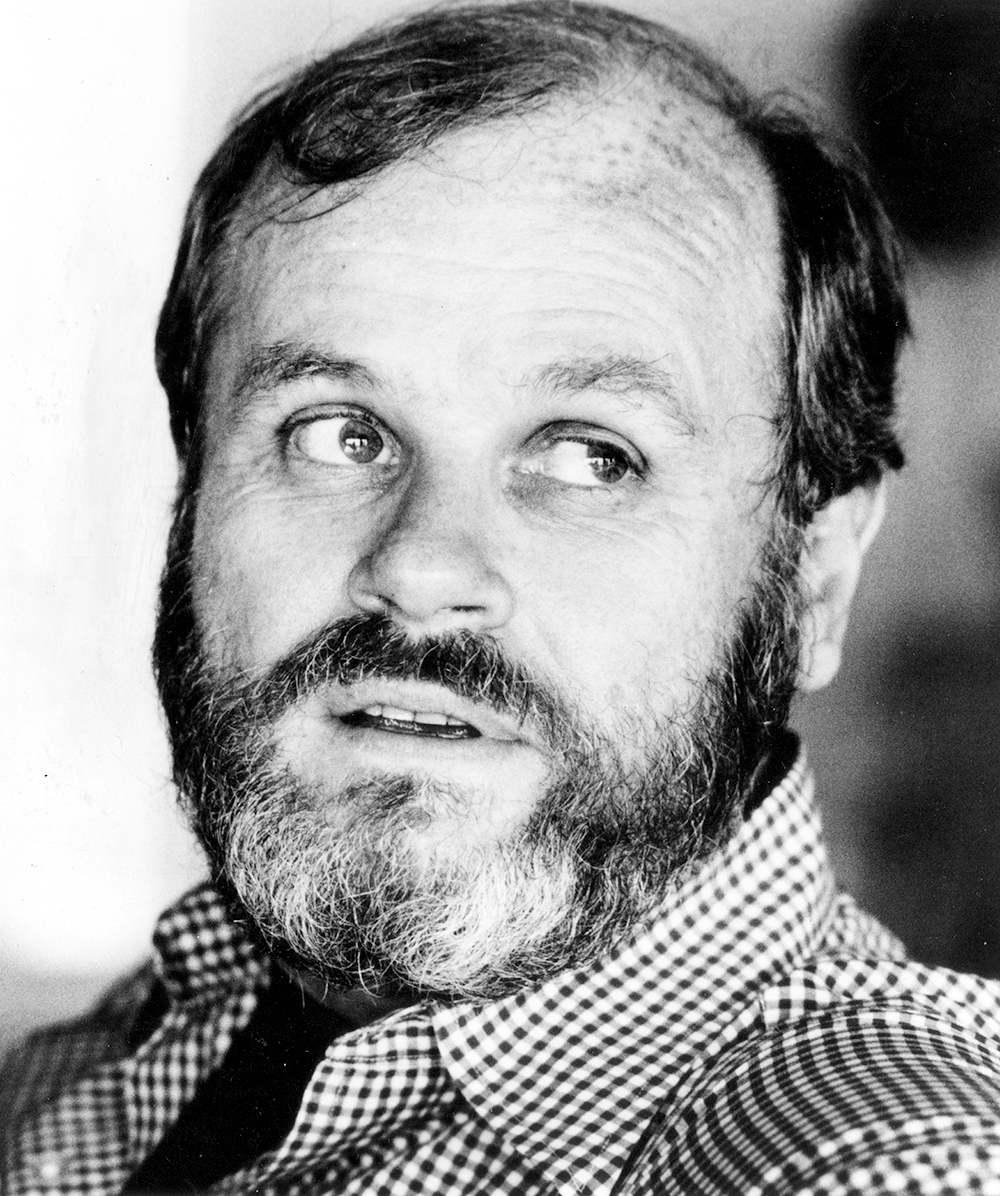

It’s a bit unfair to introduce Dunne’s newly reissued book with a quote from Didion, but the truth is he’ll always be in her shadow. Dunne was a successful journalist, novelist and screenwriter, but Didion, with whom he collaborated on magazine work and screenplays, is now enshrined in the pantheon, a heroine to hordes of aspiring littérateurs. Irony never takes a day off. Her fame rests in part on The Year of Magical Thinking (2005), her prize-winning memoir of Dunne’s death from a massive heart attack. In April, four years after her own death in 2021, Notes to John was published, and irony struck again. The book consists of her notes on sessions with her psychiatrist. Despite the title, and though the notes are addressed to Dunne, the book is not about him. The main subject is their daughter Quintana, whom they adopted as an infant in 1966, and who died 39 years later, having suffered from alcoholism most of her life. The mother-daughter bond is at the core of Notes to John, not that of husband and wife.

It would be nice to think that reissuing Vegas might redirect a little of the attention lavished on Didion, but this is unlikely. It’s a very good book, crisply written, engaging, amusing, even affecting. But it’s a period piece about a peculiar moment in time – the dying days of Vegas sleaze, before the arrival of mega resorts and the idea that gambling and prostitution could be good clean fun. In other words, Dunne gives us seedy Vegas – Vegas before Vegas was commodified – but still a Vegas we recognise: ‘An idiot Disneyland of architectural parabolas, overloaded utility poles, celestial hamburger stands and gimcrackery fairy palaces… At night it was an idiot Disneyland with lights.’

He’s good on the built environment, and even better on the people living there. His unfunny stand-up comic is a ‘$10,000-a-week never-was and never-will-be’ at the pinnacle of his career. He’s the warm-up act for Elvis. His hooker keeps detailed stats in a neat ledger of every sex act she performs. His detective is

a large bulky man with sad, quick eyes and, strangely out of context, small, immaculate hands, nails buffed, cuticles trimmed. They looked as if they had been transplanted on to the fatigued, graying mass of flesh that was the rest of him.

Dunne spends quality time with all three, watching and listening. He hears: ‘Craps is the toughest game to learn. You’ve got to know your onions to deal craps.’ And: ‘All the eagle wants to do is put you in the slam’ (meaning the government wants you in jail). The book is delightfully quotable, but there’s more to it than sleaze verbalised. There’s a moral struggle going on (that whole writer selling out thing) and some suspense, too. Will Dunne go back to his wife? As we all know, the opposite of Vegas is home.

Comments