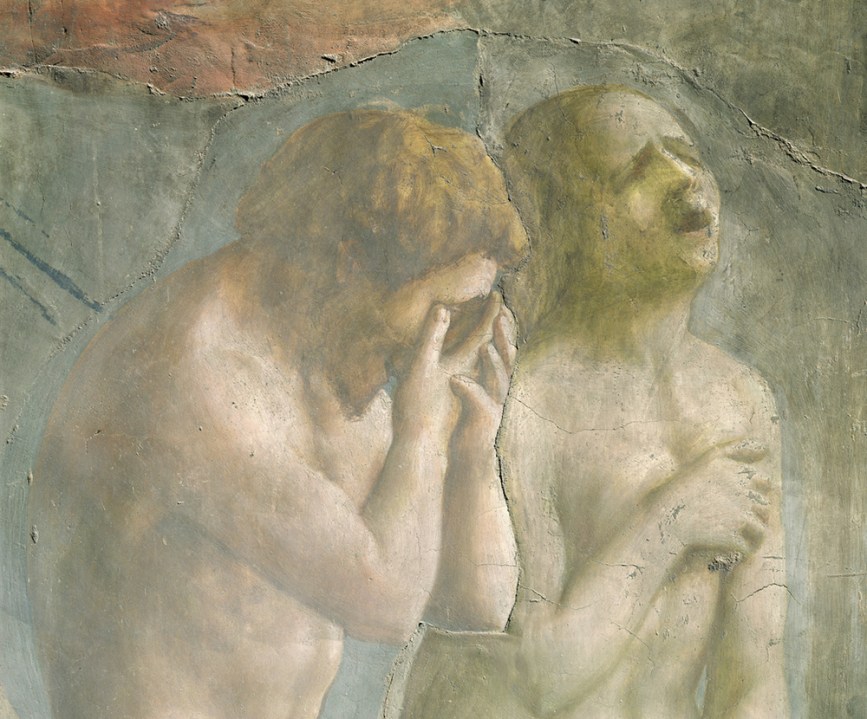

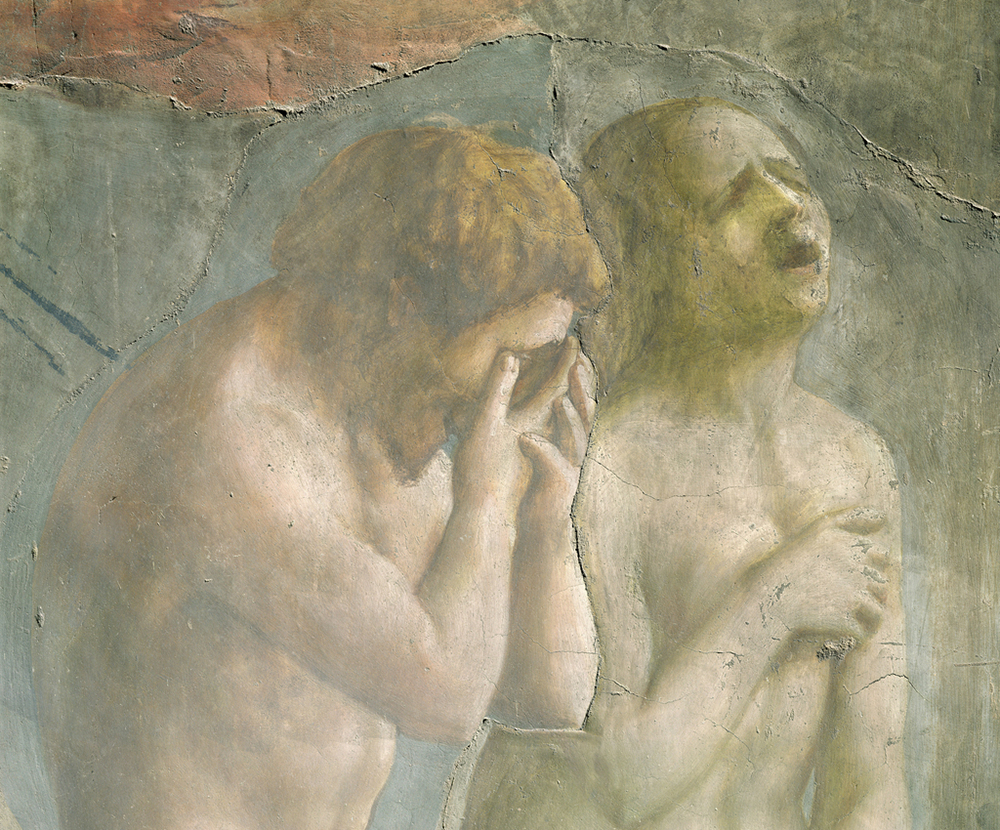

In several homilies, the late Pope Francis spoke of the ‘grace of feeling shame’. What a strange idea! Nobody wants to feel shame. Adam and Eve, after all, first felt shame only after being expelled from the Garden of Eden. Shame was God’s punishment: they felt ashamed of what had never troubled them before, namely their nakedness and their sexual desires.

But what the Pope meant, I think, is absolutely salutary for our age. Shamelessness is ubiquitous. It is the accelerant of social media that encourages us to narcissistically fire up our victimhood to a gimcrack blaze. It is why so many of us are chained to the brazen idea that we can never be wrong. It’s the seeming life strategy of the most powerful man on Earth.

In our fallen world, very few pray to God for the grace of shame, or otherwise come to feel ashamed. But for the French philosopher Frédéric Gros in this elegant book, it would be good if more did. Being a secular Parisian penseur, of course, Gros doesn’t think we need God-given gifts. But we do need grace of some kind to confront our shame. He writes:

The decision to confront [shame] amounts to a commitment to inner transformation. And this is where grace comes in, for it can be extremely difficult to completely eradicate the temptation to be lenient on oneself… We need external assistance, because otherwise it is too easy to downplay things.

Without the help of others, that’s to say, it’s hard not only to develop a conscience but also to shine the light of that conscience on oneself – to expose what one might downplay as a peccadillo and instead see it as shameful.

Both Christian spiritual advisers and Freudian shrinks, Gros notes, have delighted in the human capacity to blush. To feel a burning sensation in your throat and cheeks suggests something about you is wrong. That may well be the first step to purification, or at least ethical compunction.

Instead, what most are happy doing is shaming others, revelling in schadenfreude. Hence the story told in Jon Ronson’s harrowing look into the social media abyss, So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed. The PR executive Justine Sacco, before boarding her flight from London to Johannesburg in 2013, tweeted: ‘Going to Africa. Hope I don’t get Aids. Just kidding. I’m white!’ By the time she landed 13 hours later, what Gros calls ‘a deluge of digital hatred was raining down on her’. Staff at her hotel threatened to strike if she was allowed to stay there. Her South African family shunned her and she lost her job. Even though Sacco deleted her tweet and account, someone posted: ‘Sorry @JustineSacco, your tweet lives on forever.’ True enough. One stupid, racist and otherwise hurtful message defined this woman for all time.

One might feel sorry for Sacco (as well as hoping she has the grace to feel shame), and wonder why so many who joined the Twitter pile-on didn’t look into their own hearts. Maybe those jonesing for the hit of another’s misfortune should better do the hard work of developing humility, restraint and shame.

The Greeks called shame ‘aidos’ and made it a goddess whose name also means modesty, respect and humility

Gros, best known for his delightful A Philosophy of Walking, has written another lovely little book that might start toxic haters on a different path. But I boggled at its subtitle: ‘A Revolutionary Emotion.’ One might think that experiencing shame isn’t revolutionary but a terrible thing to feel. Consider rape victims, whose testimonies included here show how we feel shame for things of which others should properly feel ashamed.

Or think of poor Annie Ernaux. The Nobel Laureate recounted in her memoir A Woman’s Story how at school a fellow pupil recoiled because her hands smelled of bleach. Little Annie, you see, had washed her hands in the kitchen sink, only to learn that bleach was a marker of social class. The life she once took to be normal turns shameful. Her schoolmates consider that she lives in a shabby grocery-cum-café frequented by drunks and that her diction needs work. Sensitised to shame, she averts her eyes when her mother uncorks a bottle of wine, trapping it between her knees. ‘I was ashamed of her brusque manners and speech, especially when I realised how alike we were.’

Shame is different from guilt, Gros explains. One feels guilty about what one has done. By contrast, shame is ‘the state of being able to conceive oneself only within the constraints… imposed by another’. That is to say, shame is catalysed by others, particularly voyeurs – a very French theme. In Being and Nothingness, Jean-Paul Sartre imagines a Peeping Tom looking in at the keyhole of somebody’s apartment. He only feels shame when he finds himself observed by a third party. Shame is a mirror others hold up to us to make us realise what we are. Or what they think we are.

How, then, can feeling shame be a good thing? In his fabulous book Shame and Necessity, the late philosopher Bernard Williams gave us a clue. He cited Ajax rousing his friends to battle in the Iliad:

Dear friends, be men; let shame be in our hearts…Among men who feel shame, more are saved than die.

Ajax regarded shame as the desirable compunction that stopped one from fleeing battle like a coward, that steeled one to fight and perhaps die honourably before the approving gazes of one’s comrades. The Greeks called shame aidos and made it a goddess whose name also means modesty, respect and humility. But we aren’t ancient Greeks. They lived in a society of honour; we in one of shameless disinhibition.

Gros writes that shameless behaviour is ‘an absence of reserve. I flaunt myself, my qualifications, my personality, my success, my private life and my body’. We all know people like that. Perhaps you voted for them. Contrast such shamelessness with what James Baldwin felt one day strolling past newsstands on a Parisian boulevard. A single image screamed from the world’s papers: 15-year-old Dorothy Counts being spat on and reviled by a white mob as she became the first black pupil admitted to a North Carolina high school. ‘It made me furious, it filled me with both hatred and pity,’ wrote Baldwin. ‘And it made me ashamed. Some one of us should have been there with her!’

Gros glosses Baldwin’s fury, suggesting it was not just the feeling of shame of a black American looking back to his hated homeland and wishing he were there to support the poor African-American girl (which is what I took Baldwin to be saying), but as a stain on humanity, shaming each of us. ‘What did I do to prevent this?’ Gros writes. ‘Nothing.’ We should blush for shame.

Nietzsche thought shame was a poison, and his Übermenschen were utterly shameless (no wonder Hitler liked Thus Spake Zarathustra). We have become too Nietzschean. We need the wisdom of the ancient Greeks and of the late Pope, or to read this elegant book. In any event, we need to blush more.

Comments