In 2002 the remains of Sarah Baartman were buried in her South African homeland. She was among thousands of people around the world from whom body parts were collected in recent centuries and stored or displayed in museums. You might think, as tastes and norms change, returning these remains to their communities a simple thing. But a recent report from an All-Party Parliamentary Group on Afrikan Reparations urging such action has proved controversial among archaeologists.

The APPG, chaired by Bell Ribeiro-Addy MP, sets out its recommendations in a policy brief called Laying Ancestors to Rest. It calls for the outlawing of the sale of human remains, an inquiry into the use of ‘ancestral remains’ in British museums, and museums and ‘educational institutions’ to stop displaying ‘ancestral remains’.

It is this phrase, ‘ancestral remains’, that has caused disquiet among archaeologists. In a statement signed by representatives of eight archaeological organisations, they respond to the APPG’s paper, writing: ‘References to “ancestral remains” without qualification leads to ambiguity and is open to a wide variety of interpretations particularly by those who seek to use the term ancestor in support of ideological or political beliefs. This ambiguity needs to be addressed to avoid confusion and unintended consequences.’

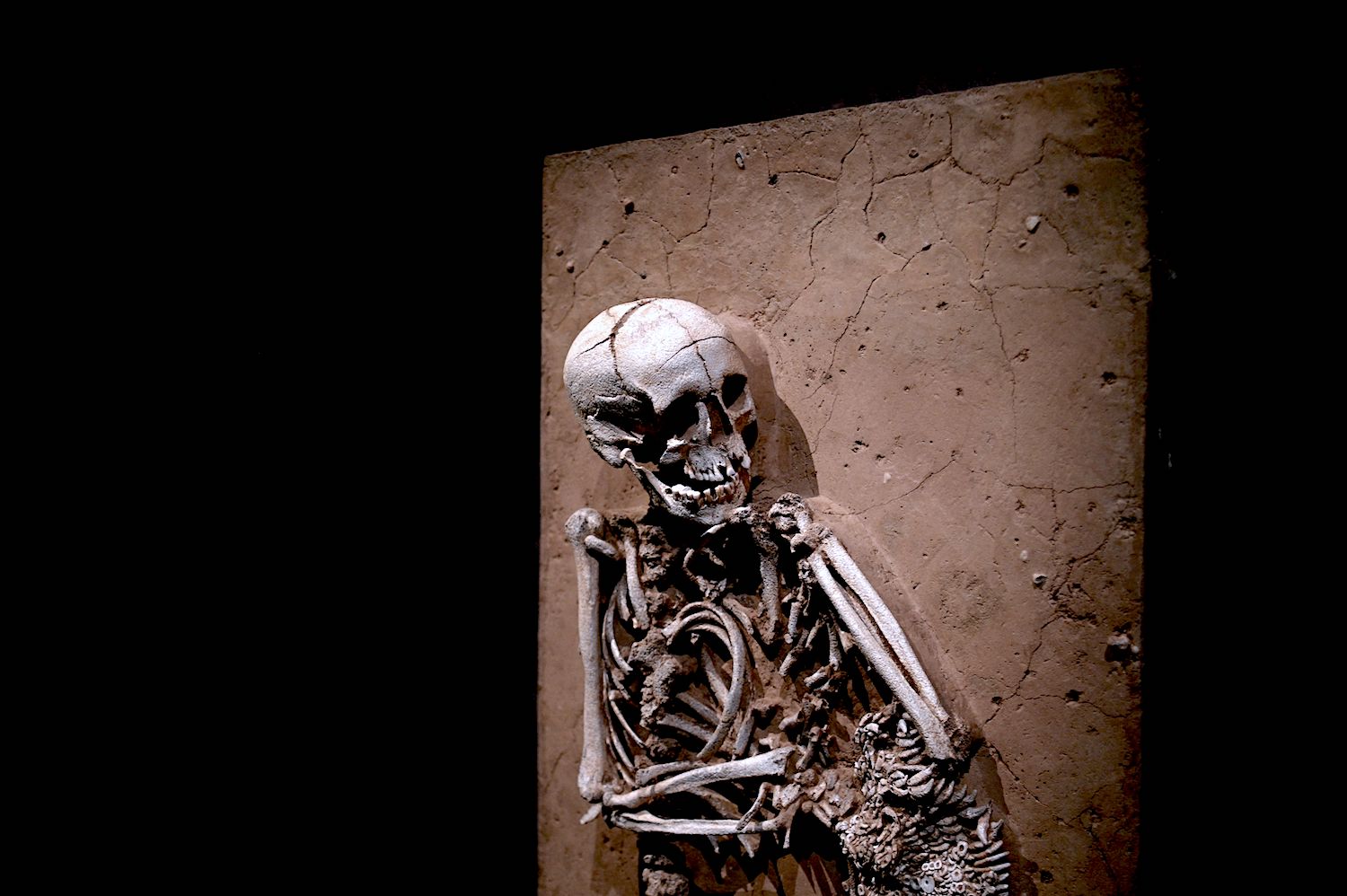

In simple terms, proving links between the living and people represented by historic remains is a minefield. In very few cases are individuals identified in museum catalogues. Even the particular cultural groups their remains came from can be unknown. The British Museum, for example, lists a jaw from Cameroon and skull parts from Nigeria, with no further information. Remains said to be from ‘Tibet/Nepal’ could originate among a wide range of ethnic and linguistic groups. The museum has a complete skeleton that might be from South America – or might not.

Could DNA help? This question was recently addressed by a group of human-remains archaeologists. Commercial DNA companies, they said, are using open-access databases of ancient DNA obtained from excavated remains, to find potential ancestors for their customers. People then ask museums about items in their collections. What if, say, someone believed they were related to a man who once lived in Roman London, and wanted to take care of his remains? Explaining that no such relationship could be demonstrated in any meaningful way would be but the start of the conversation. Identity is not just genetic. From more recent times, there might now be a variety of groups who associate with a historic population, named – who knows how accurately? – by Victorian collectors or dealers. Individuals may take quite different views on how to treat remains of people whose cultural world no longer exists.

There is much sympathy among archaeologists for the cause

The APPG nonetheless thinks ‘descendants’ have a right to determine the future of ‘ancestral remains’ (which, it says, could include associated artefacts, as determined not by museums, but by what it calls ‘source communities’). That future would, first, be returning them to where they came from, for presumed burial. If that were not possible – in which case they would be ‘orphaned ancestors… whose identities were destroyed by colonial violence’ – they should be respectfully buried in the UK. In any event, no human remains should be displayed in any institution, on grounds that they are human beings, not objects.

This argument is not new. Honouring the Ancient Dead, a Pagan lobby group, finds the very phrase ‘human remains’ offensive: they are not ‘things’, it says, ‘they are persons’. In 2008, colleagues and I excavated cremated human remains at Stonehenge (we were able to bring new sciences to the study of remains already uncovered and reburied in the 1920s). We faced a site protest from Pagans led by Arthur Pendragon, leader of the Council of British Druid Orders. They felt our work was disrespectful to the Stonehenge people. Their desire for statutory burial of all ancient remains across the UK was briefly achieved through a misunderstanding at the Ministry of Justice, which had taken responsibility for an area previously overseen by the Home Office, and was treating ancient and contemporary remains the same. Laying Ancestors to Rest, complains the archaeologists’ statement, demands similar restrictions on museum retention and display, against wider public interest shown by several surveys.

‘People, not things’ may sound hard to refute, but many human remains in museums are there because they are things. A surprising number of peoples made ornaments, musical instruments or ritual artefacts from human skulls, leg bones, hair or skin. In such cases, remains had become objects before they were collected.

There is much sympathy among archaeologists and museum professionals for the spirit of Laying Ancestors to Rest. Many are seeking ways to resolve what are highly complex issues that can take years of costly research and consultation to approach resolution. In that, at least, all seem to be agreed. Talking is good.

Comments