This piece was first published in Spectator Schools.

In 2007, many of today’s young parents were either graduates or school-leavers testing their skills in their first jobs. They were saving for a mortgage or just enjoying the freedom of being young with few responsibilities. Back then, UK average annual earnings were around £23,765. Now, they are £27,271 — a rise of just under 15 per cent. The average house price in 2007 was £181,383. Today, it’s £215,847 — a rise of more than 19 per cent. Tough on today’s young families, you may think. But the rise in house prices relative to income is nothing compared with the increase in fees for independent schools.

As with incomes and house prices, there are vast differences between north and south, rural and urban. But looking at individual schools, we see that, for example, Port Regis, a Dorset prep school, charged £18,465 for a boarding place in 2007 whereas this year the fee is £24,300 — a rise of over 31 per cent. Gateways Preparatory School in West Yorkshire charged £7,965 for a day place in 2007; today it’s £12,720 — a rise of 60 per cent. In 2007, Westminster School charged £15,963 for a day place. Today you’d pay £26,130 — a rise of nearly 64 per cent. A day place at Edinburgh’s Fettes College cost £14,859 in 2007 whereas now it’s £25,545 — that’s 72 per cent more.

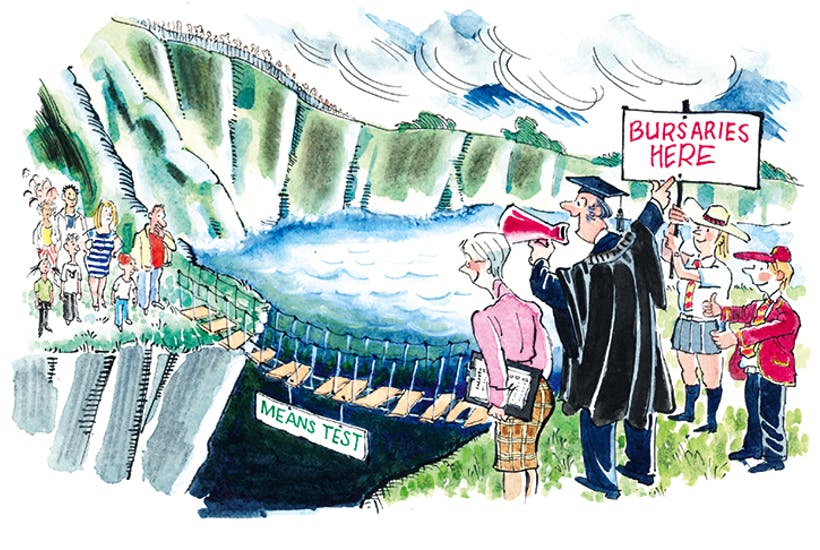

In 2007, families with a modestly above-average income could just about afford independent school fees for two children. Not now. ‘But,’ you may say, ‘I know several ordinary families with children at independent schools. How do they do it?’ The answer is ‘fee assistance’ — scholarships and, crucially, bursaries.

According to the Independent Schools Council, a third of today’s independent school pupils receive some kind of financial assistance: £900 million was disbursed in 2016-17, the largest chunk of which (£362 million) went towards means-tested bursaries. In people terms, 168,025 independent school pupils received some sort of help, and most of this came from the schools themselves. The Direct Grant and Assisted Places schemes are long gone and successive governments have put increasing pressure on schools to justify their charitable status. The schools, in response, sponsor academies, partner with state schools and open their facilities to local communities. But by far the biggest move towards inclusiveness involves the vast sums devoted to fee assistance.

Since Assisted Places was binned in 1997, independent schools, eager to attract the bright and talented children of families on moderate incomes, have built up cash reserves to let such children take up places. ‘Moderate’ is, of course, a relative term. St Paul’s School offers fee-assistance to families with a joint annual income of up to £120,000. But without assistance, the bright children of professional -parents would simply not be able to come, and it is not in the interests of the schools to become enclaves for the children of global plutocrats. Good Schools Guide clients from Russia and China insist they want their children at schools ‘without many other Russians/Chinese’.

In recent years, the amounts devoted to scholarships have remained static or even dwindled as more cash is diverted to bursary funds. Bursaries are means-tested, and some schools offer as many as ten 100 per cent bursaries a year. The shift is summed up by Mark Beard, head of London’s University College School. ‘We feel a UCS education should not be restricted to those who can afford it and offer around £1 million per annum to support bursaries… it is important that this is available to a mix of pupils from all backgrounds.’

Many of the new breed of independent school heads are genuine zealots for inclusivity. Wellington College aims to quadruple bursary funding within the next 10 years. ‘Raising money to widen access through bursaries should be every independent school’s number one priority,’ says its head, Julian Thomas. ‘A truly inclusive independent sector is good for UK education, good for the schools and good for society as a whole.’

Surprisingly, however, some schools attract few applicants for fee assistance. The reasons are unclear. When the Independent Association of Prep Schools surveyed 200 member schools, of which 125 offered 100 per cent bursaries, 9.6 per cent said they had had ‘no interest’ from parents and had offered no full bursary places in the past year. The Girls’ Day School Trust, which runs 26 schools, has accrued a large pot of money for bursaries. But several of their schools described ‘a disappointing lack of interest’. It was this gap that prompted the Good Schools Guide to set up its Scholarships and Bursaries Service — the only such national resource for parents.

The scholarship itself is not dead, and manifests itself in diverse ways. There are scholarships for clever children, for the children of seamen, the military, licensed victuallers, chemists, commercial travellers, grocers, freemasons, the clergy and for children from regions including the West Midlands and the Isle of Wight. A prep school in Warwickshire offers scholarships for Dutch hockey players. We know of one scholarship for a girl ‘with character and integrity’.

‘Whither independent education?’ you may ask —as many are. Money will always follow excellence and the irony may be that when we look again in 2027, the smartest money may have migrated to the state sector — supported, curiously, by the independent schools.

Comments