For reasons too complex to go into, while completing a doctorate in the German College in Rome in the 1990s, I shared breakfast with the then Cardinal Ratzinger every Thursday morning for nearly three years. Those breakfasts were often initially awkward because, although the Cardinal was always gracious, he had no ‘small chat’ at all and was fairly hopeless at making casual conversation. Ratzinger was a painfully shy man who did not find socialising easy.

At those breakfasts, therefore, I would engage him in theology – at which point he would come alive. I was writing a thesis on the great German theologian Karl Rahner, with whom Ratzinger had taught, and so it was easy to draw him into theological conversation about Rahnerian themes. For Ratzinger was, above all else, an intellectual. He was by nature an academic – but he was also much more than an academic. He was, in my opinion, one of the last great thinkers of the 20th century.

At breakfast, I would engage him in theology – at which point he would come alive

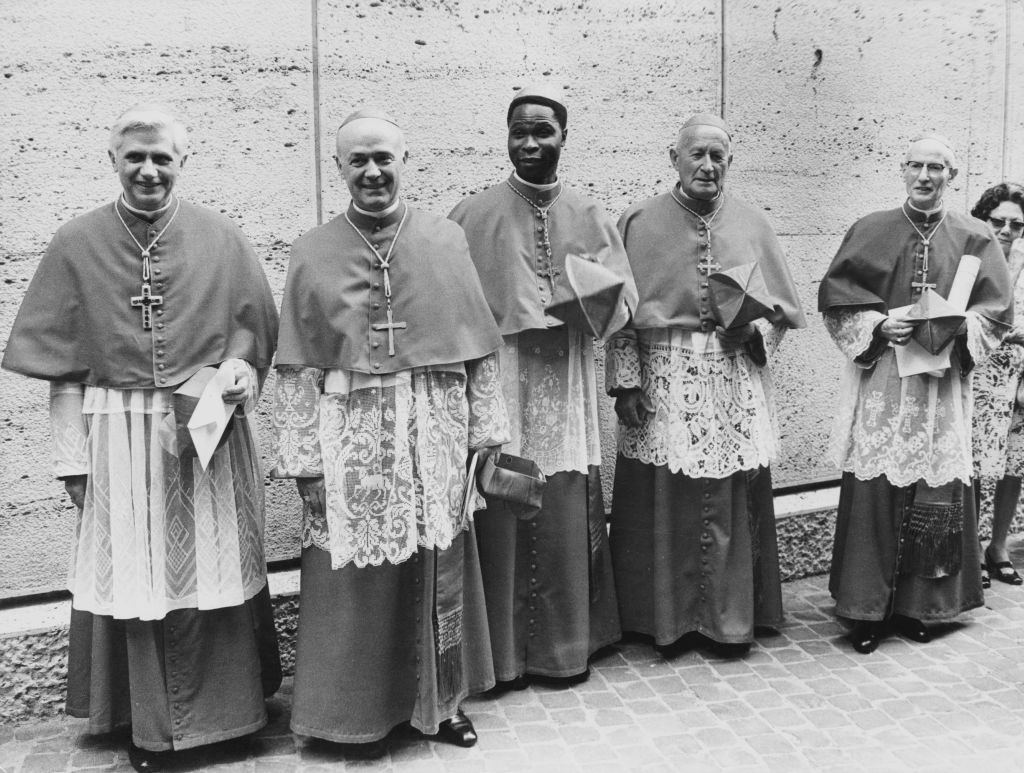

Ratzinger belonged to that flowering of Catholic theology which happened in the middle of the 20th century – when the Church was blessed with a group of outstanding theologians and philosophers who led and guided her through the profound societal change that swept Europe after the war and who helped to shape the modern Church in the wake of Vatican II. Maritain, Gilson, Lonergan, Rahner, von Balthasar, Congar, De Lubac – Ratzinger knew and had worked with them all.

And like many of them, Ratzinger was a polymath. He had an encyclopaedic knowledge of world culture, of literature, of scripture, of the arts. He could play all of Mozart’s piano sonatas, many from memory.

Much later, when working in the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, I taught a course at the Gregorian University in Rome, based on his seminal work Introduction to Christianity – which, as anyone who has read it will know, is anything but a light introduction to Christianity. I did this because I was convinced, and remain so, that in this early innovative work of his one sees traces of true brilliance. There are very few thinkers in any age who truly have something new to say – Ratzinger was one of those few really synthetic thinkers.

Unfortunately (in some ways) Ratzinger’s intellectual development was cut short when Pope Paul VI appointed him as Archbishop of Munich in 1977. Ratzinger never wanted to be a bishop and he never sought ecclesiastical advancement. Because of his shyness, he never enjoyed the social side of being a bishop and, as time went on, he found the notoriety surrounding him painful.

But Ratzinger was a man of the Church, and he did what was asked of him – and so when, three years later, Pope John Paul II asked him to become Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, he agreed without demur. In this role it was Ratzinger’s duty to elaborate Catholic faith and to clarify the boundaries of Catholic thought and this he did with unparalleled insight and lucidity. It was his duty at times to say things that were not popular with many and that jarred with the prevailing zeitgeist. But that was his job and so he did it with as much grace and charity as it was possible to have in that role.

Unfortunately, over the years, many commentators who were unable to enter into real debate or dialogue on such issues simply resorted to verbal insult, and so the caricature arose in the media of the ‘Panzer Cardinal’ who ruled the Church ‘with an iron fist in a velvet glove’. For those of us who knew him, this caricature was so radically at odds with reality that it was, and is, simply risible. For Ratzinger, like many true intellectuals, was confident in his opinions and always curious to understand the opinions of others. He was always open to discussion and never refused the opportunity for debate. In all the years I knew him and in all the years I worked with him I never once saw him become flustered or aggressive. He was never overbearing in discussion, and the idea of Ratzinger raising his voice is simply absurd to anyone who knew him.

I have never met anyone who actually knew Ratzinger and did not love him. I studied German in Munich in the 1980s and was amazed at the affection in which he was held by the burghers of that very secular town. At the German College in Rome in the 1990s I was overwhelmed by the hundreds of German pilgrims who would turn up every Thursday to celebrate mass with him at 7 a.m. When I arrived at the CDF in the 2000s I found that he was held in almost reverential awe across the whole curia because of his integrity and honesty and intelligence.

He was a man of deep faith. His spiritual writings (including Seek That Which is Above, Dogma and Preaching, Seeking God’s Face and Ministers of Your Joy) are so beautiful because they are borne out of his experience of the love of God and his deep understanding of the scriptures.

But above all Ratzinger’s legacy will be intellectual – he was an influential theologian at the Second Vatican Council; he engaged in the debate on faith and reason, championing the validity of faith in what has become a profoundly relativistic age; and he attempted to refocus Catholic scriptural exegesis through a new lens (see his three–volume Jesus of Nazareth). Ultimately, through all his theological work he sought to show how Jesus Christ is the centre of all things and gives direction and a greater horizon to human beings in an age beset by the trivialising of life and the constant reduction of the human person to something less than what Christ reveals we can be.

Ratzinger’s contribution to the life of the Church has been enormous. He was not a great administrator and, like all of us, he made mistakes. But he was a truly great man, and the world and the Church are the poorer for his passing.

Father Patrick Burke is a parish priest in the Archdiocese of St Andrews and Edinburgh.

Comments