Norman Shrapnel, the wise and kindly parliamentary correspondent of the Guardian back in the day when it was a readable newspaper, tried never to give a book a bad review. He liked to say that anyone who had taken the time and trouble to write about anything at length deserved to be given the benefit of the doubt, and so he generally dipped his reviewer’s pen in honey rather than vinegar.

I must say that on picking up Maxim Samson’s Invisible Lines, I felt quite otherwise. I wanted at first (an important caveat) to paint my laptop’s entire screen with vitriol. Within two pages I’d begun to loathe the author’s use of ‘foreground’ as a verb (technically he is not wholly wrong, just wanting in style). The idler in me wondered why he needed to boast that he is a long-distance runner, obsessively collects flags and is a master-student at Duolingo. But what really got my goat was not Samson’s fault but that of his publisher Profile for failing to equip his book with an index. Samson could perhaps have insisted; but he is a first-time author, and publishers can be intimidating beasts, always grumbling about money.

In America’s Bible Belt, millions still cleave to the belief that the Earth is only 4,000 years old and angels exist

This, though, was just my initial reaction, and I totally changed my mind when I stumbling across one unfamiliar small word halfway through the book. The word is eruv (its plural, being Hebrew, eruvim), and it was Samson’s explanation of it as a type-example of an unseen frontier that turned Invisible Lines for me into a triumph, a volume of great good sense and imagination which brims with fascinations.

An eruv sounds small, though is anything but. It is both an actual thing and a fiendishly clever concept. Physically, it is usually a wire, a string, a length of nylon fishing-line, a tiny, translucent tube, and in cities around the world it is strung between poles and parapets and pilasters to delineate an area within which Orthodox Jews may live and work and happily circumvent the harsh rabbinical laws relating to their Sabbath.

From sunset on Friday until the same time on Saturday the Torah specifically forbids observant Jews from carrying anything – keys, mobile phones, groceries, baby-strollers or indeed babies – between their home and the outside world. But the erection by the local rabbinate of an eruv solves the problem. It surrounds the city block on which you live – or your entire city, if you have enough string – such that its encirclement conflates both your home and the outside world into a single entity, so that you may transport anything hither and yon as long as you don’t step across the scarcely visible borderline.

Eruvim can be found anywhere, critics deriding them as build-your-own ghettoes. You come across them most particularly strung up high in those cities where black fur hats and frock coats and kosher bakeries abound. I was interested to read that all of Manhattan is surrounded by a 30-mile eruv and each Thursday afternoon battalions of rabbis can be observed checking to see if it has survived another week of typical New York punishment. If it breaks, the synagogues have contractors on standby to fix it, so that the fiction of the local community’s wholesale obedience to divine law may be maintained for a further seven days.

The section of the book that includes this discussion of eruvim has the running head ‘How Invisible Lines Allow Groups to Preserve their Cultural Distinctiveness’. And while not a few non-Jews might take issue with that as a rationale, other chapters are considerably less contentious.

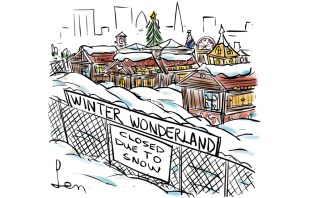

There is, for instance, the unseen line that runs through the jungles of western Sumatra, north of which women must wear hijabs, miscreants are publicly flogged and the secular ways of the rest of Indonesia are officially repudiated. There is an unmarked maritime exclusion zone five miles around North Sentinel Island in India’s Andaman chain protecting its indigenous inhabitants from all contact with outsiders and within which the Indian authorities decline to prosecute any crimes the islanders may commit. (In 2018 they killed an American evangelist who mistakenly believed that Jesus would protect him from their hail of poisoned arrows.) And there is America’s ill-defined Bible Belt, roughly from Topeka to Tallahassee and Richmond to Jackson, wherein millions cleave to the belief that Planet Earth is only 4,000 years old and that angels exist.

Some boundaries are entirely conceived of by humankind – the International Date Line, London’s Green Belt and the Tordesillas Treaty Line (which famously kept Brazil Portuguese in a continent of Spanish conquistadors, and the antimeridian of which rather less notably kept East Timor for Portugal while Spain had the Philippines). Others, mainly natural divisions, have been recognised rather than conceived. Alfred Russel Wallace noted that there were no deer in Australia and no mongooses in India, and drew a curved line through Asia and the Antipodes which still eponymises him.

Cities have often been divided by lines that have either vanished (the Berlin Wall) or have evolved, as can be seen with the varying geographical influence of the street gangs of Los Angeles. And, of course, there’s Belfast, of which the British army used to publish maps (we reporters called them tribal charts) showing where Catholics lived cheek by jowl with Protestants yet were firmly separated by an uncross-able line. That division still exists, only now it is a solid wall – the Peace Wall, laughably – topped with spikes and with stout oak and iron gates which the police slam shut each night at the witching hour.

Other sections of this endlessly interesting book deal with separations between languages and dialects, between trees and tundra, within banlieues in Paris and barrios in Buenos Aires and favelas in Rio. As the author travels the world, he tells us much that is new but also reminds us of things we only dimly think of as boundaries, since naturally they are invisible.

Shrapnel would have loved this book even more than most; and though I occasionally balked at a usage that tormented my inner pedant, I commend the work entirely. But please, Profile, think of the paperback, and with so many people, places and ideas to find within 400 pages, take pity on us non-runners, flag collectors and Duolingo dunces and give us an index.

Comments