So, you’ve fallen in love with a piece of classical music and you want to buy a recording. The problems begin when you hit Amazon. Any reasonably established classic will have been recorded numerous times: do you go for the performer you’ve already heard of? The crackly vintage recording with the gushing five-star reviews? Or the budget-priced unknown with the vaguely Slavic name; after all, it’s the same music. Isn’t it?

Radio 3’s Building a Library sorts it out so you don’t have to. Tucked away within Record Review each Saturday morning, the format is simple: every week, the BBC details a critic to listen to as many recordings of a given work as is humanly possible. Then they present their findings, playing one recording off against another before settling on a single recommendation. Over the decades, it’s been an incredibly stable formula. True, fashionable biases come and go. The library choice is invariably in squeaky-clean modern sound: if the greatest ever performance was recorded on shellac in 1938, that’s just too bad. More recently, there’ve been rumours of recordings being bumped down the list by jittery producers on #MeToo grounds.

The weekly masterclass Building a Library is as Reithian as it gets

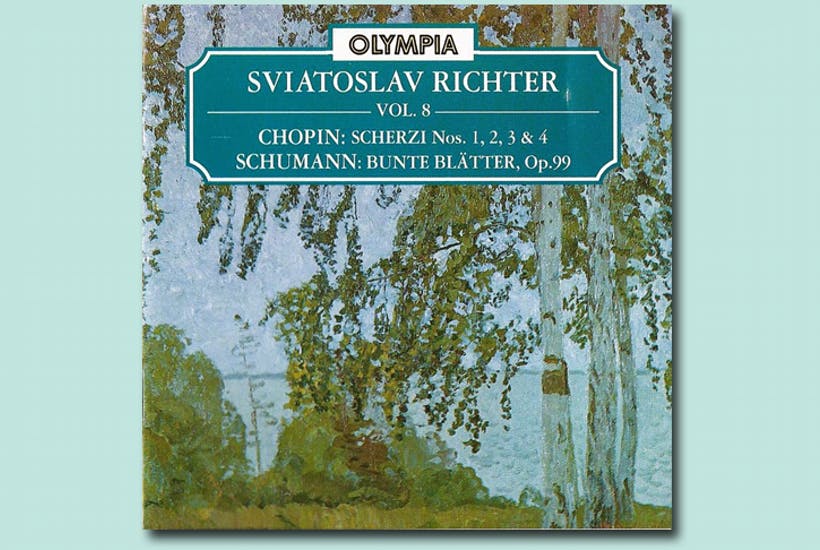

Generally, though, Building a Library is as Reithian as it gets: a weekly masterclass in the art of listening, disguised as a breakfast-time chat. This week, the subject was Chopin’s four scherzos for piano. There are at least 60 available recordings and the pianist Iain Burnside namechecked around 20 before choosing a winner that he could just as readily have picked 40 years ago: a recording from 1977 by the Russian pianist Sviatoslav Richter. ‘Nothing is light or throwaway, it all has meaning,’ he concluded; which might or might not sound like your idea of fun.

But Building a Library is about the process, and Burnside was unapologetic about his preferences. He was, he declared early on, ‘a classicist’. The presenter, Andrew McGregor, played devil’s advocate. ‘And that’s where the iceberg meets the Titanic,’ pronounced Burnside, not without relish, after letting us hear the Polish virtuoso Arthur Rubinstein make a complete horlicks of the Second Scherzo. ‘It’s thrilling playing,’ ventured McGregor, gamely. Burnside was having none of it. ‘Well, is it?’ he retorted, rearing for the kill. ‘I think it’s a disaster.’ Ka-boom: another legend hits the discards pile.

The conversational format is a fairly recent innovation, but McGregor handles his guests with a minimum of fuss, intervening to elucidate technicalities. As Burnside discussed rubato — the business of pianists slowing down or speeding up to enhance the expressive effect — McGregor quoted Liszt’s description of Chopin’s own playing: ‘Look at the trees: the wind plays in the leaves, but the tree remains the same.’ Top bantz. There’s much talk of Radio 3’s intellectual decline, but Building a Library still assumes that listeners can infer meaning from context. This is a space in which the term ‘Mendelssohnian’ can be used without self-consciousness, though a discussion of pedalling (‘so important’) sent this non-pianist straight to Wikipedia.

Still, there you go: by the end of the programme I’d acquired a working knowledge of Chopin and his interpreters, and been sent away with an unexpected new curiosity about music which, 45 minutes earlier, I’d have dismissed as tinsel. Educated, informed and entertained. In fairness, much the same goes for This Classical Life, in which the saxophonist Jess Gillam, barely out of her teens, chats to colleagues of roughly the same age about the music that they listen to for pleasure when they’re not playing for a living.

It’s a quietly subversive notion. The culture gap between the youthful stars of classical music and the predominantly (or so we’re told) greying audience that listens to them has rarely sounded more startling. Gillam talks over the music, and this isn’t the senior common room discourse of Record Review. ‘Cos it’s so spacey and like, I dunno, evocative,’ commented her guest, the pianist Leif Kaner-Lidstrom, attempting to describe an album by the jazz group The Comet Is Coming. Walton’s Belshazzar’s Feast? ‘Absolutely mental.’

Young musicians are often better at conveying the immediacy of their experience than finding formal language to describe it, and this is exactly how they talk. Gillam and Kaner-Lidstrom explored without prejudice, reacting with unfeigned delight to a vintage Yehudi Menuhin recording, and audibly moved by a lullaby composed at Theresienstadt by the Jewish composer Ilse Weber. They know their stuff. ‘Enjoying it, eh, drums?’ chuckled Gillam as Belshazzar’s Feast reached its climax. ‘I wish I could play saxophone like that,’ she commented, over a solo by Shabaka Hutchings: a moment of engaging candour from an artist whose own prowess has lit up the Proms. Like Building a Library, This Classical Life leaves you with a list of discoveries, and a sense of having glimpsed the inside workings of an art. I smiled right through it.

Comments