Few presidents can claim such an immediate success. At the end of June, I became president of my school’s alumni association and then, just five days later, the First XI won their first match at the annual Royal Grammar Schools’ Cricket Festival since 2017.

A coincidence? Well, obviously. But I’d like to think that Colchester’s youth drew confidence from me having a net at the school field on Old Colcestrians’ Day and getting hit on the bonce by the first ball I faced from the sixty something head of Year 12. If this is how poorly the alumni play, they will have thought, we can’t be all that bad.

I was never any good at cricket, much as I loved it. One presidential duty was to unveil a plaque on a new scoreboard. I observed that a plaque should also be placed on the field at square leg where a momentous event happened in 1994: I held a catch. It wasn’t even for our school. Wolverhampton Grammar were one short so our cricket master loaned his worst player. Colchester’s skipper hit the ball in the air to the one place on the ground he could be certain it would be safe – straight at me – and miraculously it stuck.

A plaque should be placed onthe field at square leg where Ionce held a catch in 1994

Returning to the school field 30 years after I left brought a wave of nostalgia. The place hadn’t changed a bit. The wooden benches, pegs and showers in the 1930s pavilion are just the same; the photos of forebears on the wall barely faded. Even Pete the groundsman was still there, though he had finally retired after 49 years of service.

What has changed is the amount of cricket played in state schools like ours. Members of the unbeaten 1975 First XI recalled, at a reunion, a season when they played 28 fixtures. This year, the school had just four, plus the week-long festival against five other royal grammars. The matches we had in the 1990s against local private schools – Felsted, Framlingham, Forest, to name just the Fs – have all been dropped.

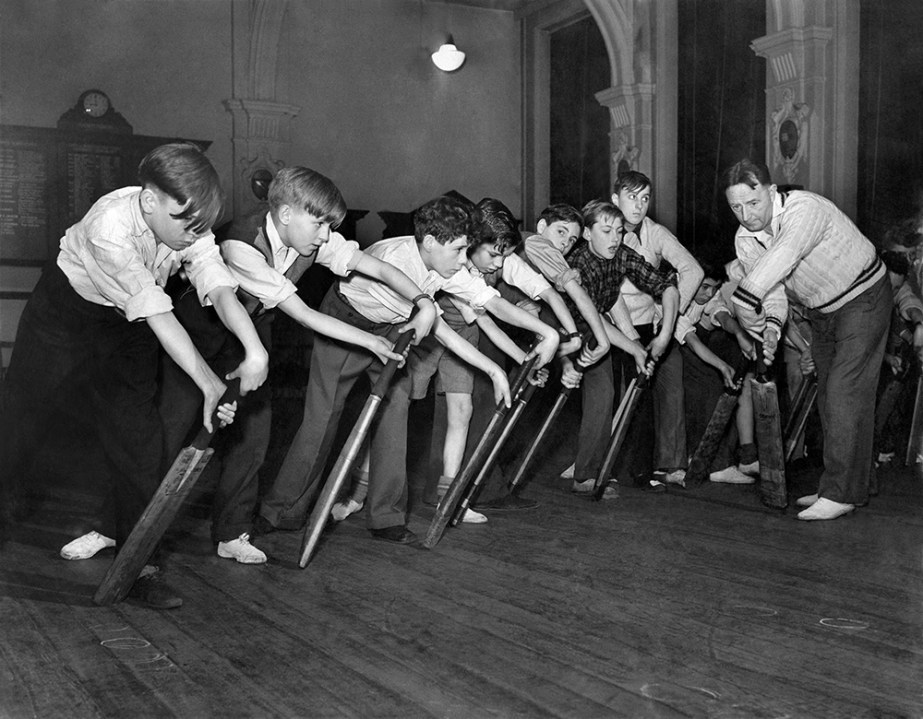

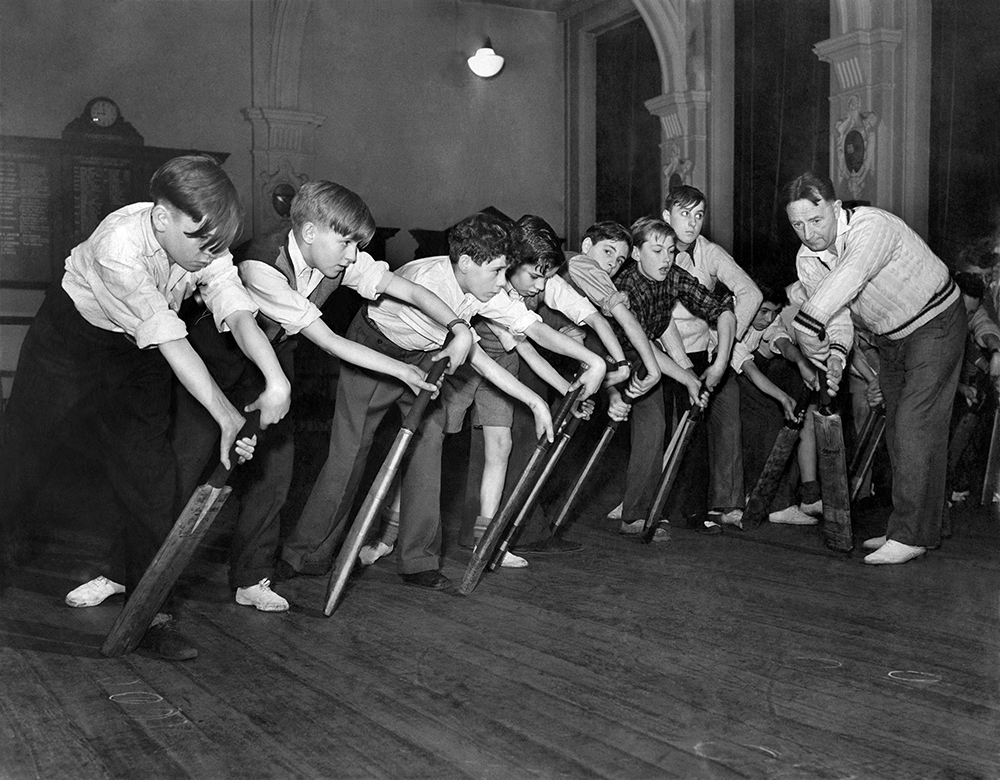

Part of it is cost: travel and equipment are areas where bursars can trim their budgets – and independent schools are eight times more likely to have grass pitches. Time is also a problem. Cricket does not suit an hour-long PE lesson for 30 mixed-ability children. And the hours given to PE in state schools fell by 13 per cent from 2011 to 2021.

Only three of the England XI that started this summer’s Test series against India were state-educated, but the England and Wales Cricket Board has a five-year strategy to boost their number by funding training for teachers and equipment. The MCC Foundation has also created hubs at 77 independent schools where they share facilities with state schools. Next year there will be a new Under-15s tournament for state school boys and girls, with a final at Lord’s – a riposte to the charge of elitism over the ground continuing to host Eton vs Harrow, as it has since 1805. And perhaps the tide is turning: Barton Peveril (not a West Indies fast bowler but a sixth-form college in Hampshire) became the first state school to reach the girls’ national final this year, where they lost to Rugby, who also won the boys’ competition.

Of course, the state and independent sectors have never quite played on the same field, even when their matches were competitive. Colchester’s glory boys of 1975 were led by Mike McEvoy, later my cricket master, who was selected for Young England Cricketers and described in Wisden as ‘the best organised batsman’ of his cohort. Yet there was no mention of Colchester RGS’s results in the 54 pages of schools’ cricket that year. That all went to independent schools.

In 2008, Wisden introduced a prize for schools cricketer of the year. The first three winners – Jonny Bairstow (St Peter’s, York), James Taylor (Shrewsbury) and Jos Buttler (King’s, Taunton) – went on to England’s Test side, as has Jacob Bethell (Rugby, 2022). Only one so far was at a state school: Teddie Casterton (High Wycombe RGS, 2018). There is a delight in flicking through old Wisdens to spot future stars as children. In the school averages for 2016, for instance, you will find Ollie Pope (Cranleigh), Zak Crawley (Tonbridge) and Harry Brook (Sedbergh), all currently in the England XI, though they were beaten to the top prize by the subsequently unheralded A.J. Woodland (St Edward’s, Oxford). Yet we must not assume that everyone who plays cricket at an independent school comes from money. Many internationals, including Bairstow, Buttler, Brook and the great Joe Root (Worksop College), had a cricket scholarship. In giving them this opportunity, the schools worked as a kind of national academy. The challenge is to discover this raw talent early and find the means to send them to the places that can nurture it.

In the 2021 Wisden, Robert Winder unearthed early reports of future heroes. We have the 13-year-old Colin Cowdrey bringing cheer to Tonbridge in 1946 by making 119 at Lord’s; the astonishing bowling figures in 1984 of Mike Atherton (Manchester Grammar) and Nasser Hussain (Forest School), two future England captains who became much better known for batting; and Imran Khan, who played for Pakistan while at Worcester RGS, being outshone in the national school averages by the famously slow-scoring Chris Tavaré (Sevenoaks). What a privilege it must have been to spot these titans before they started to shave.

The joy of school cricket is summed up best in that feature by Bob Barber, who holds the record for the highest score by an England batsman on the first day of an Ashes Test. In 1953, Barber achieved the double for Ruthin School of 1,000 runs and 100 wickets. Recalling those days, he said: ‘It was happy cricket, that was the thing. I strongly believe that if you want people to play well they’ve got to be happy. I don’t remember any stress. That big green field at Ruthin – it’s always sunny when you’re young, isn’t it?’ And shouldn’t that be the goal of all schools: to give their pupils sunny memories?

Comments