The publication of the King James Bible was not only a watershed moment in the history of publishing; it also had a decisive impact on the history of reading.

In 1611, the Bible was already the exemplary book. It was not only the source of authoritative content; it was the model for how to read other books. The apparatus that makes it possible to divide a written text into its constituent elements and examine them separately – chapter and section headings, footnotes and cross-references, and so on – originates with Biblical scholarship, and the King James Bible made these tools available to a mass audience for the first time. Subsequent theories of interpretation in general and of translation in particular both derive from the tradition of biblical exegesis, as does the concept of literary criticism; but since the rise of the novel in the nineteenth century, the sacred origins of literary culture have been forgotten.

The genre of ‘alternate history’ usually involves reimagining crucial historical events, such as the outcome of the Second World War (‘What if the Germans had won?’). An alternate kind of alternate history might instead involve reimagining crucial cultural events like the publication of the King James Bible. What if it had remained the exemplary book into the nineteenth century? What if we read novels in the same way that the Protestant translators read the scriptures in 1611?

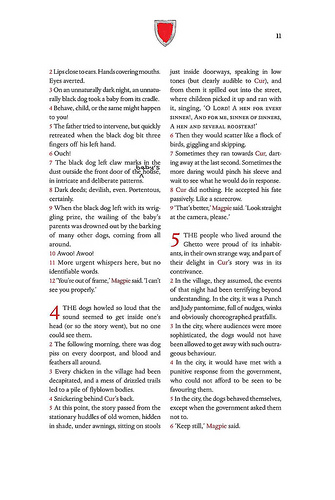

My novel Five Wounds attempts to answer these questions. Five Wounds is therefore laid out like the King James Bible, as if the text comes to us via a caste of priestly interpreters. It is broken into named ‘books’, then broken again within these books into internal numbered chapters and numbered verses, which are displayed in two-columns. Moreover, the names of each of the five protagonists are always rendered in red: that is, as ‘wounds’ on the page, a device adapted from so-called Red Letter editions of the Bible, in which words spoken by Christ are so marked. Quotations incorporated within the text (of which there are many, including several from the King James Bible itself) are rendered in SMALL CAPITALS, which is how citations from the Old Testament are conventionally rendered within the New Testament. Below is a sample page (click on the image to expand).

Five Wounds is obviously not a sacred text. On the contrary, it is an irreverent fantasy, whose literary form is inspired as much by fairy tales as by scripture. The design alludes to this

contradiction, since the apparently authoritative typeset text is accompanied by occasional scribbled, handwritten corrections, as if it has gone through the hands of an editor who doubts its

canonical status. The same confusion bleeds out into the story. For example, one of the protagonists, Gabriella, is a crippled angel, whose ability to receive messages from God is severely

compromised by poor reception. Every interpretation she offers is therefore based on a corrupt text, which is garbled and incomplete.

Gabriella, faced with an apocryphal text like that of Five Wounds, might ask: What is it that makes a sacred text sacred? One answer is that such texts are inspired. An inspired text is conceived of as a single, spontaneous, seamless utterance, which cannot be edited, corrected or abridged. It is immaculate, because it is linked to the divine, which speaks through the author, who in this case is merely a proxy. Because it is always in the process of coming into being, it remains eternally present. It is immune to obsolescence. This is exactly how the translators in 1611 read the scriptures.

The problem is that the apparatus that accumulates around such a text actually undermines this idea, just as the evolution of the church as an institution, with its own internal hierarchies and ideas of orthodoxy, might be said to betray its original principles: its original divine ‘inspiration’. The accumulated tradition of interpretation gives the Bible a history, and in the Catholic Church that history explicitly becomes part of its meaning. The Biblical text can only be approached through a succession of commentaries upon it, which determine its current meaning.

By contrast, the publication of the King James Bible in 1611 was an attempt to restore the ‘eternally present’ aspect of the Bible. According to the 1611 translators, the Bible was quite capable of speaking for itself, direct to its readers in every present moment, because it still carried within itself its original spark of divine inspiration.

As a young reader of the King James Bible, one of my difficulties was that this presumption was patently false. Many passages were boring, or even apparently meaningless. They felt like the opposite of inspired, especially in the Old Testament, which includes long genealogies, and repetitive and incredibly detailed descriptions of obscure ritual objects, whose physical form remained utterly unimaginable, despite all this detail. It is undeniable, even to the most ardent Protestant theologian, that such passages require interpretation to explain their significance: that is, they require some historical context, which therefore must locate (part of) their meaning in the past rather than in an eternal present.

The elaborate design of Five Wounds frames a lowly exercise in genre storytelling as an object of fetishistic devotion, and thereby suggests an even more cynical response. Perhaps you can make anything ‘sacred’ simply by framing it in a certain way, just as you can call anything ‘art’ if you stick it on a gallery wall. One should be sceptical of such obvious rhetorical gambits, but one should also be suspicious of Romantic prose that tries to seduce the reader by trumpeting its inspired status.

The publication of the King James Bible in 1611 was supposed to mark a definitive break with the medieval (Catholic) past, and a return to a renewed apostolic present through a Pentecostal

dispensation, in which each man and woman would hear the Gospel in their own tongue: in this case, English. Five Wounds suggests the impossibility of achieving such a break. The division of the

novel’s text into chapters and verses locates its meaning in the past: it already has a history of interpretation attached to it. By contrast, the addition of the handwritten corrections

locates its meaning in the present: it is still (always) in the process of coming into being. The text is also ‘illuminated’ by multiple illustrations and annotations, which were

created by Dan Hallett, and which are an integral aspect of the storytelling.

Protestantism has close connections to iconoclasm, but here words and pictures are not separate entities. Each bleeds into the other on the page. The blasphemous marginalia of medieval manuscripts

cannot be separated from the pure Word of God.

The modern paperback is not a natural object. The advent of e-books has made this painfully obvious. In the current state of confusion as to what a book is or should be, it might be an opportune moment to review the sacred prehistory of the novel. Five Wounds reaffirms the relevance of the King James Bible to modern storytelling, but it also draws on medieval traditions that were erased in 1611, just as the novel erased its own sacred origins.

History is our greatest resource for innovation, but only if we are willing to reimagine what actually happened.

Jonathan Walker is the author of Five Wounds: An Illuminated Novel (Allen & Unwin) and Pistols! Treason! Murder!: The Rise and Fall of a Master Spy (Johns Hopkins University Press)

Comments