In the body of chess rules, castling is a clumsy protuberance. Once per game, you get to move king and rook at the same time, with a bewildering list of exceptions. (One dreads having to broach these gotchas with a novice opponent who has castled improperly.) Despite its convoluted logic, castling is nothing more than a convenience, and the game could function perfectly well without it.

Five hundred years ago, the rules of chess were still evolving, with significant regional variations. The ‘king’s leap’, a precursor of modern castling, permitted the king to make one move as a knight jump (perhaps from e1 to g2), while in other forms it could step two squares any which way (so, for example, e1 to g3 was also on the menu). If the latter sounds wacky, at least it is congruous with the way in which pawns can jump two squares on their first move. The interleaving of king and rook in modern castling looks peculiarly arbitrary.

The late 15th century saw a seismic shift, when a variant became popular which upgraded the powers of what we now call the bishop and queen, hitherto much less agile pieces. Since the standards of defensive play were lamentable (as they were even in 1850), it must have seemed imperative to secure the king’s position. But perhaps the appeal was even stronger for the gambiteer, who could exploit it to accelerate an attack. In the 16th century, the Italian player Polerio analysed the gambit 1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 Bc4 g4 5 O-O, which would lose much of its oomph if White could not castle.

In modern chess, experienced players almost always castle. World-class players learn counters against standard openings with more precision every year, so it is harder than ever to light the touchpaper on a game. That’s one reason why the former world champion Vladimir Kramnik has been an enthusiastic advocate for ‘No-castling chess’, which he researched after his retirement from competitive play in 2019. It’s a creative constraint with a profound impact, as players must rethink their strategy from the very first moves.

Earlier this month, Kramnik took on his great career rival Viswanathan Anand in a four-game ‘No castling’ match in Dortmund, which was won 2.5-1.5 by Anand. The fourth game, below, saw a sparkling fight. Perhaps Anand is well suited to this variant. It is an amusing anomaly that during their 2008 world championship match in Bonn, Anand forwent castling in five separate games.

Vladimir Kramnik–Viswanathan Anand

No castling chess match, Dortmund 2021

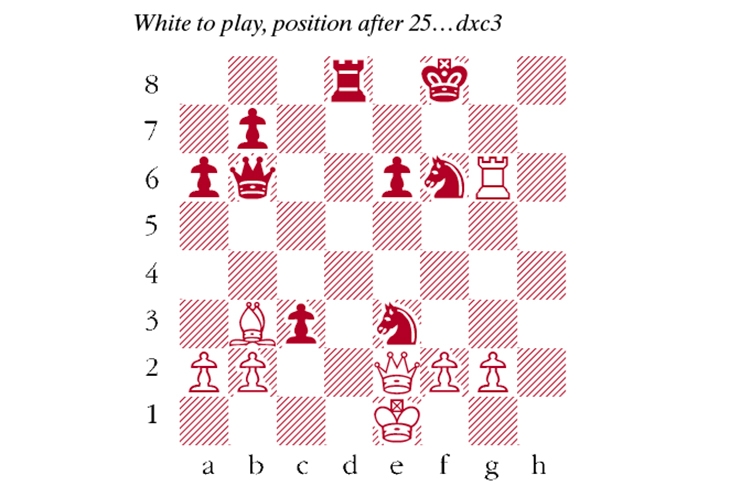

1 c4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 c5 4 cxd5 exd5 5 Nf3 Be6 6 Bf4 Nc6 7 e3 a6 8 dxc5 Bxc5 9 Ng5 Nf6 10 Nxe6 fxe6 11 Bd3 Bd6 12 Bg3 Bxg3 13 hxg3 Ke7 The preceding exchange of dark-squared bishops has made this square relatively hospitable to the king. 14 Qe2 h5 15 Rd1 Ne5 16 Bc2 Qb6 17 Bb3 Rad8 18 Rd4 Nc6 19 Rdh4 When the king remains in the centre, such eccentric measures to coordinate the rooks are justified. 19…Ne5 20 g4!? Clever. 20…Nexg4 21 Rxh5 Rxh5 22 Rxh5 Nxe3 22…Nxh5 23 Qxg4 Rh8 24 Qh4+ and g2-g4 regains material 23 Rg5 d4 24 Rxg7+ Kf8 25 Rg6 dxc3 (see diagram)

26 Qf3! A crucial resource in a wild position. Instead 26 Rxf6+ Kg7 27 Rxe6? (27 Rf3 is better) c2! 28 Bxc2 Qb4+ forces mate. 26…Qd4 27 Rxf6+ Kg7 28 Rf7+ Kg8 29 fxe3 Qd2+ 30 Kf1 cxb2 31 Qg4+ The only way to draw, returning the rook to force perpetual check. 31…Kxf7 32 Qxe6+ Kg7 33 Qe7+ Kh8 34 Qf6+ Kh7 35 Qf7+ Kh8 36 Qh5+ Kg7 37 Qg5+ Kh7 38 Qh5+ Kg7 39 Qf7+ Kh8 40 Qh5+ Draw agreed

Comments