Coalitions, as David Cameron has discovered, are tricky things to manage. How much more difficult, then, was it for Winston Churchill as he struggled to survive, then win, a world war, while at the same time managing his fractious three-party administration at home.

In this scholarly, yet grippingly readable study of the wartime coalition, Jonathan Schneer, an Anglophile American academic, reveals how much of a myth the popular legend of a political class and nation united behind their belligerent war leader truly was.

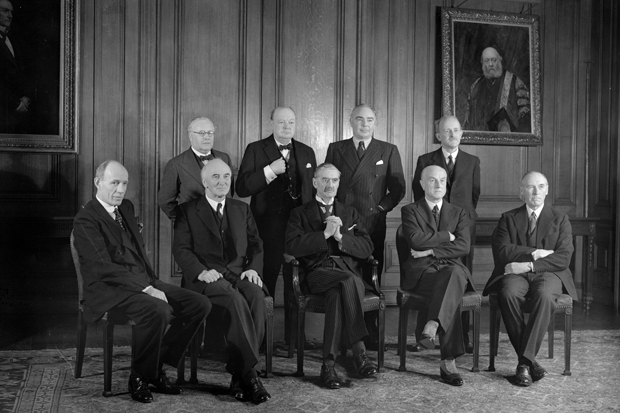

Rather than the resolute, single-minded team rolling up their sleeves for the coming fight as portrayed by David Low in his famous cartoon ‘All Behind You, Winston’ published in the Evening Standard on 14 May 1940, Schneer shows us a team of rivals riven by personal as well as political discord, plotting to replace the great man who led them.

As Churchill himself wrote of his equally ferocious hero Georges Clemenceau when ‘the Tiger’ was appointed premier of France in the first world war, his reluctant fellow politicians ‘would have done anything to avoid putting him there, but having put him there felt they must obey’.

That distrust of Churchill, and reluctance to put him in power, was particularly pronounced in his own Conservative party. Not only had he, in his own words, ‘ratted’ from the Tories to the Liberals and then ‘re-ratted’ back again; his long career had been littered with errors and disasters that would have destroyed a lesser man.

The bloody beaches of Gallipoli, returning to the gold standard, opposing Indian independence and backing the wretched Edward VIII during the abdication crisis were the inglorious milestones where Churchill had either spectacularly fouled up or found himself isolated on the wrong side of history.

But in the supreme crisis of 1940, as Hitler’s armies overran first Denmark and Norway and then invaded France, Belgium and Luxembourg, only one question mattered: who had a consistent record in opposing the appeasement of Nazi Germany, and who had the necessary qualities of ruthless resolution required to fight and win the war? Churchill’s was the only name left in the hat.

Naturally, the arch-architect of appeasement, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, did not see things that way. He clung to office by his bony fingers when it was clear that Parliament and country had lost confidence in his half-hearted leadership. Even then he tried to shoehorn his appeasing soulmate foreign secretary Lord Halifax into the premiership to block Churchill. Only when the Labour party refused to serve under Halifax and the noble Lord himself demurred could Churchill claim the grudgingly proffered prize.

Safely installed in No. 10 at last, with Labour’s Attlee, Bevin, Morrison and Dalton given top jobs, and his old Great War comrade Archie Sinclair of the Liberals given the air ministry, Churchill, sensing the hostility felt by many Tories towards him, moved cautiously. He kept Chamberlain in the cabinet until the ex-PM died, and he moved Halifax to Washington as ambassador. Another appeaser, Sam Hoare, was sent to Madrid.

Once the immediate threat of invasion had passed, anti-Churchill plotting resumed in earnest. One by one Schneer knocks down the ninepins who contemplated replacing Churchill during one of the war’s many setbacks. First up was Sir Stafford Cripps, the Tony Benn of his day, upper-class socialist, puritanical and high-minded, of whom Churchill witheringly remarked ‘There but for the grace of God, goes God.’ As with the right-wing appeasers, Churchill dealt with Cripps’s leftist threat by despatching him abroad as ambassador to Soviet Russia — and enjoyed a good laugh with Stalin behind Cripps’s stiff back over his teetotal vegetarianism.

The next contender for the crown came from Churchill’s own inner circle in the puckish shape of Lord Beaverbrook. Recognising the Beaver’s qualities of drive and efficiency, Churchill made the press baron minister of aircraft production, at which he succeeded so spectacularly that he fancied himself for higher things. Churchill thought otherwise and neutralised him by letting him resign.

All the time, the gravest threat sat at Churchill’s elbow in cabinet — his quietly able deputy Clement Attlee. While Churchill ran the war gallivanting round the world, Attlee, doggedly loyal to his chief though he was, minded the shop at home, approving such crucial domestic legislation as the 1943 Beveridge report proposing the welfare state and flabby appeaser Rab Butler’s 1944 Education Act. Not much interested in such humdrum stuff, Churchill failed to notice that the country was changing before his eyes. He sneeringly referred to Attlee as ‘a modest little man with much to be modest about’; but in the 1945 Labour landslide, the modest little man trounced the old warrior and created the Britain we live in today.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £17 Tel: 08430 600033

Comments