For centuries, liberals have fought to be judged by the personal qualities they can change, not by the characteristics that none of us can alter – most obviously, our race. But today’s Lammy Review into how people from ethnic minorities are treated by the criminal justice system insists on treating race as the most important thing about each of us. It operates on the assumption that, if there are disparities in economic and social outcomes, then this must be the result of discrimination.

The report admits that there are other reasons for disparate outcomes – such as lone parenthood. But instead of accepting that its claim of discrimination has been contradicted, it puts out a press release asserting that ethnic minorities face bias, including overt discrimination. BBC Radio 4 loyally reported Mr Lammy had found ‘evidence’ of overt discrimination. Really? The section of the report in which the accusation is made says only this:

‘My conclusion is that BAME [black, Asian and minority ethnic] individuals still face bias, including overt discrimination, in parts of the justice system. Prejudice has declined but still exists in wider society – it would be a surprise if it was entirely absent from criminal justice settings.’ (p. 69.)

His reasoning seems to be that overt discrimination must be there because it still exists elsewhere. Well, it may. But the point of an official investigation is to find out whether or not there is any objective evidence of discrimination. He did not find any – and should have said so.

He did find some racial disparities. His favourite example is that members of ethnic minorities are more likely to plead not guilty. This leads to jury trials, which can result in longer sentences in the event of a guilty verdict. Their decision to plead not guilty (and thus go without the one-third reduction in sentence that is given for pleading guilty) is blamed on the criminal justice system:

‘The CJS must also be trusted by those who engage with it, if outcomes are to improve. The difference in plea decisions between BAME and White defendants is the most obvious example of this – with BAME defendants pleading not guilty to 40% of charges, compared with White defendants doing so for 31% of charges. … Plea decisions currently exacerbate disproportionate representation.’ (p. 69.)

He finds that the reason so many BAME defendants plead not guilty is that they see the system in terms of ‘them and us’:

‘Many do not trust the promises made to them by their own solicitors, let alone the officers in a police station warning them to admit guilt. What begins as a ‘no comment’ interview can quickly become a Crown Court trial.’ (p. 6.) The answer, says Lammy, is to remove one of the biggest symbols of an ‘us and them’ culture – the lack of diversity among those making important decisions, from prison officers and governors, to the magistrates and the judiciary. (p. 6.)

A closer look suggests that a failure to trust solicitors may not be the correct explanation. A report by the Centre For Justice Innovation has found a significant disparity in acquittal rates at Crown Court. BAME men and women were respectively 9% and 8% more likely to be acquitted compared to similar white men and women (pdf). Perhaps minority ethnic defendants are aware of the higher acquittal rate and prefer to take their chances with a jury than with experienced magistrates who have heard every excuse in the book many times over.

Or, perhaps they knew of the studies of juries commissioned by the Ministry of Justice to discover whether or not there was evidence of racial bias. Published in 2007, one report looked at all jury verdicts over a two-year period in England and Wales and concluded (pdf) that there was no tendency to convict black or Asian defendants more often than white defendants.

The system is fair, and yet Mr Lammy asserts that trust is low not just among defendants and offenders, but among the ethnic minority population as a whole. His evidence is that a ‘bespoke analysis’ for his review found that 51% of people from BAME backgrounds believed that ‘the criminal justice system discriminates against particular groups and individuals’.

Far more reliable and, more to the point, more easily checked by independent observers, are the various measures of trust provided by the Crime Survey England and Wales for many years now. People are asked to say whether they agree or disagree with these statements: ‘The police would treat you with respect’; and ‘The police would treat you fairly’. The results are broken down by ethnic status.

When white people were asked if the police would treat them with respect, 86% agreed. The total for non-whites was 82%, with a disparity between Asian and black respondents: 85% for Asians and 75% for black Britons. When asked if they would be treated fairly, the score for whites was 65% and non-whites 67%. Again, ethnic groups differ: 72% of Asians thought they would be treated fairly, 73% of ‘Chinese/other’, and 54% of black respondents. By coincidence, exactly the same proportion of Guardian readers thought they would be treated fairly, 54%.

There is also a question about whether the criminal justice system as whole is fair. The survey for 2013-14 found that 64% of white people thought the system was fair, compared with 71% of non-whites. Again, there is a variation between ethnic groups: 75% of Asians thought it was fair, 79% of ‘other ethnic’ minorities, and 62% of black Britons.

A large majority think that the system is fair, and confidence among non-whites is higher than among whites. Does this not call for an explanation? Not in Mr Lammy’s view. His selective use of statistics suggests that he was determined to find discrimination whether it was there or not. He goes on to conclude that the Government should set a national target to ensure that judges and magistrates mirror the ethnic breakdown of the general population by 2025. He does so when there was no reason to believe that the ethnic status of judges and magistrates influences their decisions. We should aim to appoint judges who believe in justice, regardless of their skin colour, and who can swear the judicial oath of office with complete sincerity:

“I do swear by Almighty God that I will well and truly serve our Sovereign Lady Queen Elizabeth the Second in the office of judge, and I will do right to all manner of people after the laws and usages of this realm, without fear or favour, affection or ill will.”

We are not entitled to be policed or judged by our own kind. It would not matter if every police officer, every magistrate, and every judge were black or Asian, so long as they were sincerely committed to justice. Promoting our heritage of justice is what the government should focus on, and recruiting people who believe in justice and objectivity should be the public-policy target, not racial quotas.

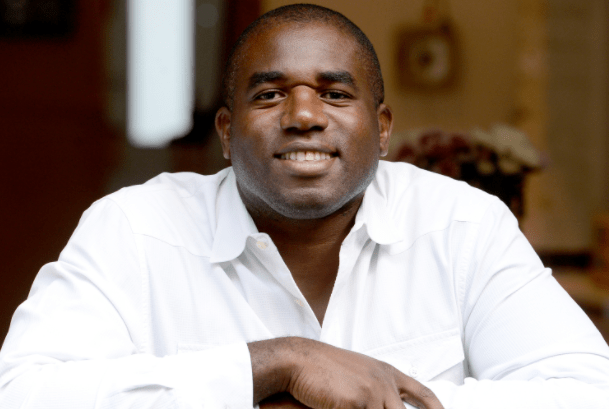

David G. Green is CEO of Civitas

Comments