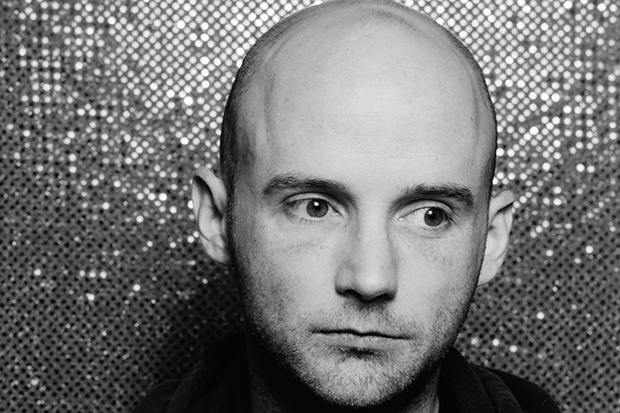

In 2002 I flew to New York to interview the dance music producer whose 1999 release Play remains the bestselling electronica album of all time. A few years earlier, Moby had been known as a teetotal Christian vegan, an ascetic anomaly in a scene built on hedonism, so there was something comic about his new-found reputation as a promiscuous party monster.

The photo-shoot paid homage to Jimi Hendrix’s Electric Ladyland, with Moby posing in a cardigan, reading a magazine, oblivious to the 18 naked women surrounding him. (No, this concept wouldn’t fly in 2019.) The headline was ‘Death of a Ladies’ Man’. As we spoke, Moby struck me as charmingly candid and self-aware, but he was clearly lying (perhaps to himself as much as to me) when he claimed that his life was returning to normal. As Then It Fell Apart reveals, he continued to pursue sex, drugs, alcohol and approval with deranged gusto for several more years. The book opens in 2008, with a desperate, self-loathing Moby attempting to suffocate himself to death.

Discovering that fame, wealth and debauchery don’t plug the emotional abyss after all is an old story, but Richard Melville Hall (as Moby was born) tells it exceptionally well. His authorial debut Porcelain, covering the decade prior to Play, was a rare treat. While the majority of music memoirs plod dutifully from A to Z, entertaining only the most loyal fans, this one displayed genuine literary ambition and a flair for indelible anecdotes, earning Moby a sequel.

The out-of-the-blue nature of Play’s phenomenal success makes his story unusually relatable. Some musicians dream and scheme their way towards fame, but for Moby it was a bizarre plot twist. In 1999 he was a floundering 33-year-old who thought he was releasing ‘a flawed and poorly mixed swan song’ — until it sold 12 million copies and transformed his life to a psychedelic degree. A skinny, bald bedroom producer was suddenly granted the status of rock star.

Then It Fell Apart intercuts the ‘shiny lunacy’ of the post-Play years with memories of Moby’s youth in generally prosperous Darien, Connecticut, where his widowed mother navigated countless dead-end jobs and dead-loss boyfriends. But the dual timeline doesn’t pay off. While it’s important to establish why a dreamy, anxious kid who grew up on an island of poverty in an ocean of privilege would eventually turn into a ‘Faustian running dog’, desperate for the love of people he didn’t even like, the flashbacks become increasingly distracting. Even the most deftly told story of learning to DJ or losing his virginity struggles to compete with a 21st-century music industry version of the last days of Sodom.

On that topic, Moby’s tone is neither boastful nor ashamed, but quizzical and sardonic. Look at this poor fool, he seems to be saying, with his threesomes and gated estate and outrageous sense of entitlement. How does he think this will end? But he doesn’t make the mistake of downplaying the elation before the fall. ‘Fame had saved me and made me whole’ lands with heavy irony, but you can see why he believed it for a while. Fame is a corridor punctuated by a series of doors; all you have to do is walk through each one that opens to you.

Moby did, which is how he ended up rubbing shoulders (and other body parts) with a panoply of colourful characters which includes Hillary Clinton, Donald Trump, Natalie Portman, David Lynch, Salman Rushdie, Vladimir Putin’s daughter, a pre-fame Lana Del Rey and a furious Eminem. ‘I wanted to carpe every single diem as compulsively and degenerately as I could,’ he explains. As La Dolce Vita curdles into Satyricon, he aspires to becoming a spectacular wreck. When a disgusted friend tells him ‘You are chaos’, he takes it as a compliment. He may be in the gutter but he’s drinking with the stars.

Books about addiction are inevitably repetitive because addiction is repetitive, and one cocaine-maddened night on the tiles eventually blurs into another; but Moby’s prose remains sprightly. After a long night of crystal meth and angel dust, he feels like ‘a demon with broken teeth’. Moscow’s Red Square resembles ‘a fairytale prison’. David Bowie’s ‘Heroes’, which Moby finds himself practising in his apartment with the man himself, is ‘sad and calm, like an abandoned space station’.

He writes particularly well about episodes of joy, with the surprising result that a memoir about ruinous excess might still inspire envy in some readers. Perhaps you would savour the glittering parties and celebrity encounters without going too far. Perhaps you would be wise and resilient enough to say no more often than Moby did. Maybe so, says this arresting account of a success more toxic than failure — but don’t be so sure.

Then It Fell Apart

Author: Moby

Publisher: Faber

Pages: 394

Price: £14.99

Comments