This year’s Turner Prize has four winners rather than one. In a letter to the jury, the artists claimed that it would be wrong to adjudicate between the social causes championed in their art. So in the end, they split the spoils between them.

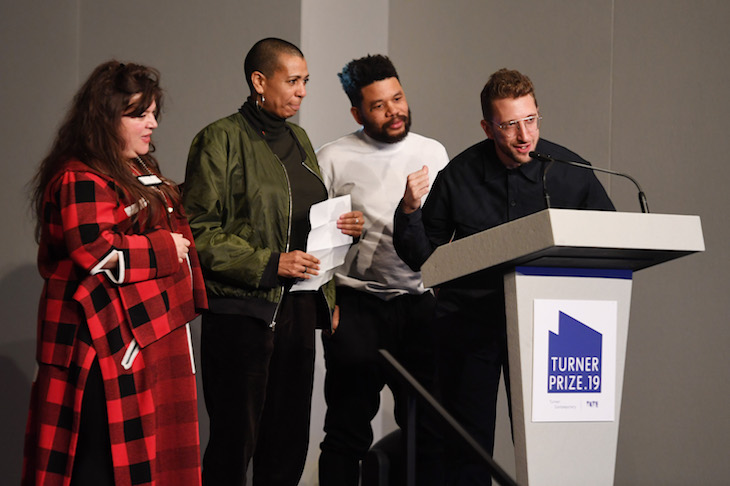

The judges had one job: to judge. Instead, they acquiesced to the candidates they were meant to be assessing. Instead of one name, poor Edward Enninful, the editor of Vogue, charged with opening the envelope at the ceremony in Margate, saw four: Oscar Murillo, Tai Shani, Helen Cammock and Lawrence Abu Hamdan.

‘Here’s something quite extraordinary,’ Enninful said, presumably off the cuff. ‘At a time of political division in Britain and conflict in much of the world, the artists wanted to use the occasion of the Turner Prize to make a strong statement of community and solidarity and have formed themselves into a collective.’

It’s a very noble idea, but is the Turner an art prize or a morality test? Did the artists not want to be judged on their creativity? And couldn’t the jury pick a winner by judging who had made the best art?

Even if you agree with the dubious premise of deciding the winning work based on its social value, why split the prize?

If the Turner panel were to have picked Cammock’s film, which stresses the role of women during the Northern Irish Troubles of the late 1960s, ahead of Shani’s vision of a post-patriarchal utopia, would that really suggest a political preference that denigrates the message of the runner-up?

Great art can make very strong political statements (think of Picasso’s ‘Guernica’, painted to highlight General Franco’s horrific bombing of the eponymous Basque town during the Spanish Civil War), but only a Marxist would say true artistic creativity should be measured in terms of social worth.

By abandoning their responsibility, the Turner judges are following the lead of the Booker jury, who last month awarded the literary prize to two authors: Margaret Atwood and Bernardine Evaristo. Panels are odd numbered precisely to stop this sort of fudge. And yet the five judges could not decide who most deserved the award.

Up to a point, none of this ought to matter. The very notion of prizes is arbitrary. They are a conceit. To state the obvious, unlike in the 100 metres, there is no objective standard that determines the best work of art or literature. But if you’re going to have a prize, do the decent thing and make a judgment. A shortlist of four is the equivalent of a sporting semi-final. Perhaps FIFA will look into employing the Turner logic to keep more teams happy at Qatar 2022. And least under that metric, England would be three-time world champions.

A cynic would say that by proposing the split, the four artists were hedging their bets. Sure, they will have to divide the £40,000 cheque, but they will each gain a great deal of visibility. Ask someone in his native Colombia who Oscar Murillo is, and they’ll tell you he’s a centre-back who is rarely picked for national team.

The chairman of the prize Alex Farquharson, also the director of Tate Britain, said that surprises were part of what kept the award relevant. But there’s a fine line between a surprise and a gimmick. Too many gimmicks and you have a joke.

Sure, if you have a lot of respect for the adjudicators then prizes provide a tangible yardstick to judge quality, one that is not tied to sales figures. It is an easy way for the reading or artistically-minded public to keep tabs on the cultural zeitgeist. But the act of elevating certain authors and artists above others of roughly equal strength can also encourage laziness. By aggrandising usually one (or this year, two or four works), many casual onlookers are inevitably pushed in a direction that homogenises our reading or viewing. In other words, the impact of giving an influential cultural prize deepens society’s echo chamber.

The Booker and Turner prizes promote the arts and controversies such as this year’s ‘decisions’ might place culture more firmly in the national conversation. But does anyone who is not already deeply invested in the literary or the art world really care? A football fan will be able to reel off a list of Premier League winners, but can many culture vultures do the same with the Booker or the Turner?

Coming so soon after the Booker was split last month, it is high time we turned a blind eye to prizes.

Comments