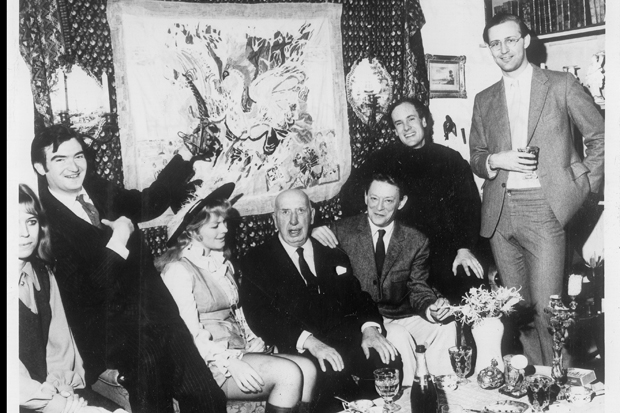

In his time, Gerald Hamilton (1890–1970) was an almost legendary figure, but he is now remembered — if at all — as the model for the genial conman in Christopher Isherwood’s novel Mr Norris Changes Trains (1935). ‘There are some incidents in my career, as you doubtless know, which are very easily capable of misinterpretation,’ Arthur Norris tells the book’s narrator, and Hamilton affected to be deeply shocked by the assorted vices attributed to his fictional alter ego. He nevertheless exploited the connection throughout his long and disgraceful life.

When Isherwood met him, Hamilton (né Souter) was employed in Berlin by the Times as its German sales representative. He also moonlighted as a fixer for Willi Münzenberg, ‘the notorious communist, who presides in Berlin on behalf of Moscow over the doings of the League Against Imperialism and Friends of Soviet Russia’, as British Intelligence described him. Though it sounds too good to be true, Hamilton was lured into sharing accommodation with ‘the Great Beast’, Aleister Crowley, who took time out from practising the black arts to report back to Special Branch in London on his flatmate’s Comintern activities. The two men were well matched, because Hamilton himself spent much of his time spying on people and selling information, and although he did not quite acquire Crowley’s public reputation as the embodiment of evil, he was at one time described as ‘the wickedest man in Europe’.

Opinions vary as to quite how wicked Hamilton really was. Isherwood portrayed Norris as a lovable rogue, though he would later admit that ‘beneath his amiable surface’, he was ‘an icy cynic’ whose misdeeds were ‘tiresome rather than amusing’. Stephen Spender regarded Hamilton as genuinely evil, responsible for driving to suicide a young man he was blackmailing. John Lehmann was also repelled, complaining that Isherwood didn’t care in the least whether the people he befriended were ‘good or evil, destructive and corrupt or life-enhancing. All he wants is that they should be good Isherwood copy.’ One of the extraordinary things about Hamilton is that even those he treated shabbily or worse nevertheless felt that their lives had been enhanced by knowing him, and thus forgave him.

Although Isherwood lent a hand, Hamilton was the principal creator of his own legend. Discovering the truth behind the tall stories is a fraught undertaking, not least because Hamilton wrote three autobiographies — As Young as Sophocles (1937), Mr Norris and I (1956) and The Way It Was With Me (1969) — which give wholly different versions of even the most basic biographical information. Other accounts of Hamilton’s life provide further strategic obfuscation: Robin Maugham’s five-part ‘exposé’ in the People newspaper was in fact concocted in collusion with Hamilton, while John Symonds’s splendid Conversations with Gerald (1974) allowed the old reprobate to spin yet more yarns.

Now comes The Man Who Was Norris by the late Tom Cullen, a book blocked during the author’s lifetime for legal reasons — in part by Maugham, for whom Hamilton apparently procured boys. The manuscript was retrieved by Reed Searle from Cullen’s flat after his death; he supplies a biograph-ical afterword about the author, and the book has been skilfully prepared for publication by Phil Baker, who provides source notes, explanatory footnotes and a lively introduction.

Cullen was assiduous in consulting original documents, interviewing friends and associates, and ferreting out the facts from a warren of false trails and blind alleys, and he rarely makes the mistake of taking Hamilton at his own word or estimation. For example, far from being a close friend of Roger Casement, as Hamilton frequently claimed, it seems likely that the two men never even met; nor is there any evidence that Hamilton used his many implausible though genuine European royal connections to procure foreign titles on behalf of Maundy Gregory (the subject of an earlier book by Cullen).

On the other hand, he really did have private audiences with Pope Benedict XV, in which he persuaded the pontiff to issue an encyclical ordering a special collection to be taken in every Catholic church on Holy Innocents’ Day in 1919 for the benefit of the Save the Children Fund, of which Hamilton was an unlikely envoy. He was also employed as a go-between or informer by various agencies, including Sinn Fein, Special Branch, and the British Military Mission in Berlin. These missions were undertaken not out of patriotism, political conviction or a sense of public duty, but for cash: either in exchange for (not always reliable) information or in the form of fraudulently claimed expenses.

If Hamilton could work as a double agent, so much the better for his always precarious finances. The law occasionally caught up with him and he served prison sentences for bankruptcy, theft, gross indecency and being a threat to national security. He wiled away a wartime spell in Brixton prison by teaching French to his fellow inmate Sir Oswald Mosley, whom (his earlier communist sympathies notwithstanding), he greatly admired, and his corpulent body provided the model for Oscar Nemon’s Guildhall statue of Winston Churchill, whom he detested. He wrote a disgraceful book in support of South Africa’s apartheid regime, published in the immediate wake of the Sharpeville massacre, and approached various other unsavoury regimes (Smith’s Rhodesia, Franco’s Spain) in the hope of getting similar commissions.

Cullen notes that Hamilton and his sometime associate Frank Harris were ‘the last of the gentleman adventurers — a gentleman adventurer being defined as one who, if forced to use a lead pipe, is careful to wrap it in a silk scarf’. This certainly describes Hamilton, whose impeccable dress and manners concealed a core of brutally wielded self-interest, a readiness to betray any friend or cause in exchange for the wherewithal to finance his badly underfinanced but grotesquely extravagant style of living.

Baker notes Hamilton’s Zelig-like propensity to pop up at historically significant events, and Cullen’s book is among other things a kind of alternative account of the 20th century viewed through the distorted prism of his subject’s monstrous but engaging character. Well researched, properly sceptical, written in a nicely relaxed style, and often uproariously funny, this is absolutely the biography Hamilton both needed and deserves.

Comments