Kenya

As late as the 1920s, it was believed that Africa’s tropical sun would boil a European’s brains. ‘The direct ray of the sun – almost vertical at all seasons of the year – strikes down on man and beast alike,’ Churchill had written on his visit to East Africa. ‘Woe to the white man whom he finds uncovered!’ When my father first arrived in Tanganyika he was advised to go about in a spine pad and solar topee, which he swiftly discarded. He wore a khaki drill bush shirt and shorts as long and baggy as spinnakers. In old age his face, neck, arms and legs were very dark brown, but his torso remained a much paler colour.

As a boy I also went about in khaki shorts, made by the Indian tailors in old Malindi town. All the white boys like me wore shorts, which made sense in the heat. It was also a kind of uniform we all had while we drank Tusker beers at Ocean Sports, a beach bar on the Kenya coast we affectionately called ‘Open Shorts’. Home for the holidays from school in England, my mother would observe how white I was, give me a jug of cooking oil to pour over my skin and tell me to get out into the sun.

After university in England I became a correspondent in Tanzania, where the citizens expressed discomfort at my habit of wearing shorts. A friend explained that such attire was regarded as colonial, a symbol of white oppression. I was appalled and since I did not wish to offend anybody, I opted for long trousers. In all my years of journalism, I wore longs, however hot it became in the scorching sun’s rays of Somalia, Ethiopia or Sudan. When I began farming 20 years ago I returned to wearing shorts occasionally, but even now my friends tend to laugh at my white knees.

The other day I joined a queue of ageing Europeans in the waiting room at the dermatologist in Nairobi. Business was brisk. Inside, as I lay stripped down to my boxer shorts, the doctor scanned my 57-year-old hide, squirting a jet of liquid nitrogen on a mole here and there. After the examination he announced I had no melanomas, no squamous carcinomas. ‘You look like a man who didn’t grow up in Africa,’ he said, surprised when I told him how much of my life had been spent here.

A friend explained that shorts were regarded as colonial, a symbol of white oppression. I was appalled

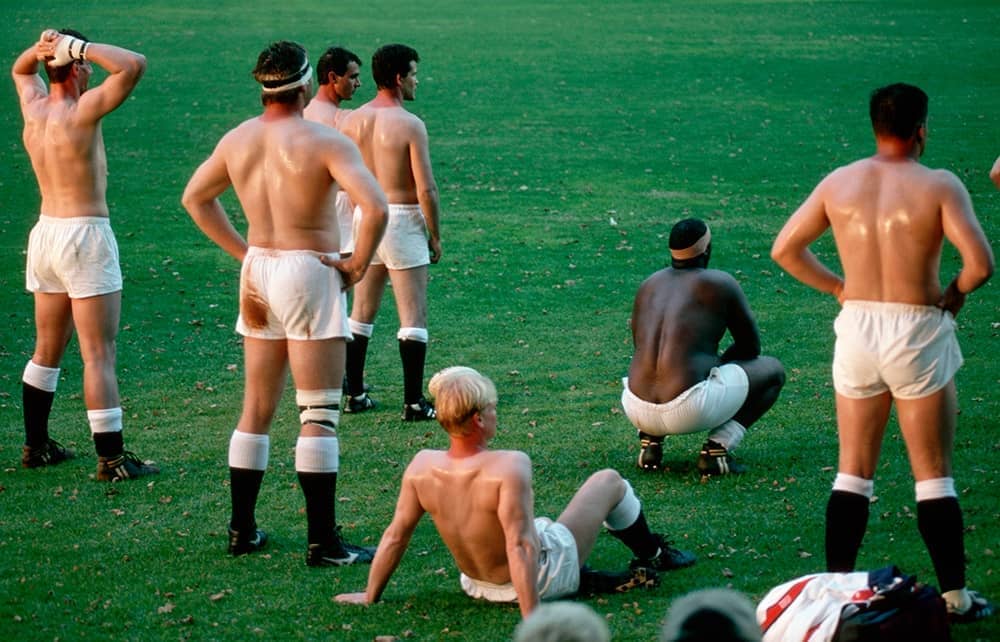

Zimbabwean author Hannes Wessels tells me that the habit of wearing shorts in East Africa might have been started by Rhodesian forces fighting General von Lettow-Vorbeck. The fashion spread to the British Army and colonial troops in the wars across Africa and Burma. Hannes sent me a series of photographs of Rhodesian soldiers in shorts that begin with the long pantaloons of the 1940s. In those days, to be properly dressed a man also had to wear long stockings almost to the knee. Through later decades the kecks get ever shorter until, during the Rhodesian civil war, the images are of young Rhodesian Light Infantry and SAS fighters in what we call ‘ball-breakers’. The idea, Hannes explains to me, was that the guys needed to move fast in the bush. They were dressed as if in the gym, with floppy hats, T-shirts, ball-breakers and Veldskoens worn without socks.

Still today across Africa, shorts are a form of attire that white folk celebrate as a treasured part of their identity. We have never seen the bizarre Australian fashion of ‘short suits’, of smart jackets worn with formal short pants. In cities people wear longs with their suits but whenever permitted I think we still hanker for the echo of life on safari and on the farms. The youth have taken to brightly coloured surfing board shorts and crazy styles with lots of pockets. On any well-turned-out bushman, a Leatherman multi-purpose knife and even a special pouch in which to keep one’s mobile phone hang from a Maasai-style beaded belt.

I now notice many indigenous Africans have taken to shorts too, not just on the beach but upcountry. Fashion designers are producing designs in ethnic prints. More women are wearing shorts and hot pants. Gone are the days when the likes of Julius Nyerere and Hastings Banda could enforce their purges against mini-skirts, bell-bottoms and sideburns. Hems are going up across the liberated new Africa (apart from some Muslim nations). Could it be that we are finally laying to rest the associations of a colonial past?

Comments