Until recently, football was viewed with suspicion in independent schools – the poor relation to its big-hitting step-brother, rugby. That well known saying about football being ‘a game for gentlemen played by hooligans’ seemed to sum up independent schools’ attitudes perfectly. Well into the new millennium, promising young players would be cajoled into playing rugby or hockey: anything rather than – shock, horror – football.

This aversion helps explain why professional footballers are usually state-educated. England’s rugby coach, Eddie Jones, may have lambasted public schools for ruining English rugby; he could never have said the same for football. Privately educated Premier League players could barely put together a first XI: Callum Hudson-Odoi (Whitgift and Chelsea), Tyrone Mings (Millfield and Aston Villa), Nick Pope (King’s School, Ely and Newcastle), Fraser Forster (Royal Grammar School, Newcastle, and Tottenham) and Patrick Bamford (Nottingham High School and Leeds). Bamford even had to play rugby until Year 11 because of the lack of football teams at his independent school. Indeed he revealed to talkSPORT last year that he had issues being a professional footballer from a private school: ‘People assume that I never had to work for anything, which is total nonsense… There was this misconception that I’m a really posh guy.’

Football hasn’t always been sidelined by independent schools. After all, leading public schools such as Eton, Harrow, Winchester, Westminster and Charterhouse were influential in setting up the Football Association in 1863. Charles W. Alcock, the man who launched the FA Cup in 1871, was an Old Harrovian who played for Wanderers FC, the FA Cup’s first winning team, predominantly an Old Boys side. From 1872 to 1882, the FA Cup was regularly won by such teams – including Wanderers on five separate occasions, as well as the Old Etonians and the Old Carthusians. In the early days of England internationals these schools provided many of the players: Eton alone had 39 England internationals between 1873 and 1903. The Westminster vs Charterhouse football fixture, first contested in 1863, is supposedly the longest continuous football fixture in the world. Both sides competed for the right to wear pink. An Australian coach visiting Charterhouse nearly 150 years later remarked: ‘Was that really a prize worth winning?’

Fortunately, attitudes towards the game are changing. The clamour to play football among fee-paying pupils is a trend few schools can afford to ignore. After all, these teenagers support Premier League teams (usually the most predictable); why should they be denied the chance to play the game themselves on all those magnificent pitches?

I’ve coached football at Radley College, traditionally a rugby school, and seen this surge in football’s popularity first-hand. A decade ago there was already some disquiet at Radley boys being forced to play rugby or hockey rather than football, but there are still rules in place at more traditional schools about those sports taking precedence for junior years. When I first started coaching, it was not unusual to hear the occasional rugby-mad teacher refer dismissively to the round ball game as ‘oik-ball’.

Despite such attitudes and restrictions, the sport is growing, to the extent that Radley now puts out seven senior teams, as do some other well known rugby-playing schools like Tonbridge. This coming season, even Rugby School itself will field six football teams in competitive matches – although, rather like Patrick Bamford’s experiences at Nottingham, no fixtures are planned for boys in Years 9 and 10 and only a single fixture has been planned for Rugby’s girls.

The clamour to play football among fee-paying pupils is a trend few schools can afford to ignore

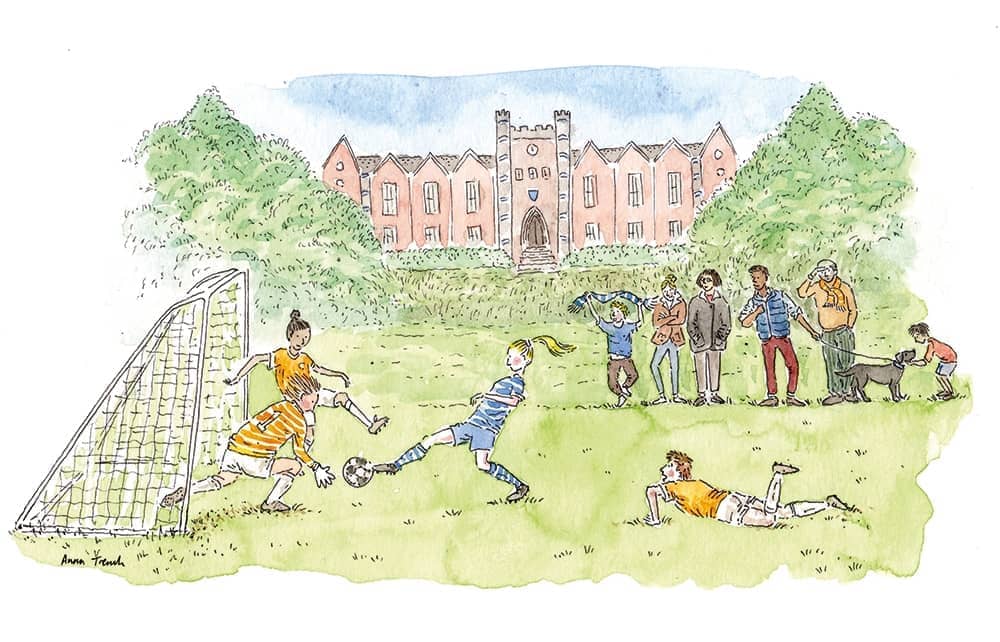

Of course playing football at independent schools is never quite the same as playing in the local park. Think pristine pitches and wingers called Toby and Freddie. Think parents turning up in Audis, Cayennes and Countrymen. The corner flags out, the goal nets trim and tidy, the school banners unfurled proudly in the autumn wind. The shouts of encouragement from the occasional over-excited dad are usually polite, with ‘Oh, do come on, Archie!’. Some things are the same though: coaches have to put up with the occasional intrusive parent demanding their son be subbed on immediately.

Yet even in independents, football club budgets never seem to match the better-resourced funding for more traditional sports. Pre-season football tours rarely reach exotic locations. End-of-season celebrations are never as lavish as those in other major sports. As for the much-prized sports kit, or ‘stash’, handed out to coaches as a perk for the freezing hours they spend standing on February touchlines, football coaches may just about be given a bobble hat branded in the school colours for their pains.

But although we football coaches sometimes feel a little short-changed, we’re still just as involved with our teams’ successes and failures, especially at tense times in the season. The lower Radley teams I coach tend to be beaten by arch-rivals Tonbridge. But on one memorable occasion we managed to salvage a draw, with a late goal scored by the team rogue, who nearly didn’t play, as he turned up late for the bus. As he scored the goal that saved the game, I found myself jumping up and down on the touchline like a less combative Antonio Conte. Most of the other spectators were still politely patting their Labradors.

One thing is certain. Football is changing from the predominantly male, working-class game of the last century. Only last month the England Lionesses asked the government to provide more football in schools across the board. Some private schools have been slow to cater for girls’ football: I recently overheard two secondary pupils on a Cornish beach, one sporting the hoodie of a leading school, lamenting the fact that they were still being forced to play hockey or netball. Even top schools like St Paul’s Girls’ School put on only one football fixture for the 2021/22 season and there were no fixtures at all in previous seasons for its 770 girls. The same is largely true for other illustrious girls’ schools, like Cheltenham Ladies’ College and Benenden.

But attitudes there are changing too and no doubt the Lionesses’ success will mean more interest in the sport. The Independent Schools Football Association has already launched a ‘Girls Football Strategy’ – citing the ‘negative perception of football’ as one of the challenges the sport faces. Encouragingly, the ISFA has reported that ‘the last five years have seen huge growth in the number of teams’ and also noted ‘an increasing demand for girls’ football’.

So perhaps, at long last, independent school prejudices against the people’s game may finally go the same way as all those 1980s footballers’ haircuts.

Comments