Naturally, the start of the new school year is often stressful for pupils. Perhaps those anxious children returning to their classrooms this week could follow the example of Milly, a young Lancashire student. When picking up her GCSE results from her school, Tarleton Academy, near Preston, she brought her ‘best friend’ Kevin – a four-year-old ram.

Milly says Kevin is her ‘therapy sheep’. He accompanies her ‘pretty much everywhere’. He was her date to the school prom, wearing a halter to match her dress. Milly seems resilient enough: later this year she is going to compete in the Young Shepherd of the Year competition. Perhaps her unwillingness to be parted from Kevin displays her dedication to her work. But by branding him her ‘therapy’ animal, Milly was making a greater claim for him – suggesting she needed him to calm her nerves. In doing so, she was, consciously or not, joining a fad that is getting out of hand.

Traditionally, a therapy animal has been a trained animal, mostly a dog, that provides support and comfort to the unwell or unhappy in hospitals or nursing homes. They have a long history. In the late 18th century at the York Retreat, a home for the mentally ill, patients were encouraged to interact with the domestic animals around the grounds. Both Florence Nightingale and Sigmund Freud championed the medical benefits of animal interaction and for over a century the US military has used dogs to help soldiers with PTSD.

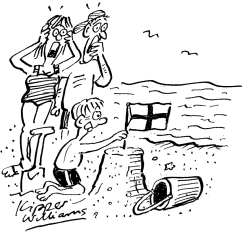

Today, animals are still regularly taken into care settings. Even if the scientific evidence is variable, common sense suggests a visit from a friendly pet can cheer up someone who’s suffering. But the concept of therapy animals is rapidly spreading out from the roles you might expect – comforting children with cancer, say, or brightening the day of dementia patients – and gambolling into every aspect of day-to-day life. These are the so-called emotional support animals (ESAs).

ESAs were first popularised, as so many questionable ideas are, on American college campuses. They were supposed to provide support for people with mental-health conditions or psychiatric disabilities, but have become an excuse for people unable or unwilling to separate themselves from their pets, however exotic. Pigs, snakes, tigers and alligators have all been reported as ESAs. It’s hard not to conclude that at least some of these are a cry for attention. Take Wally, an emotional support alligator for Joie Henney of Pennsylvania. Henney claims Wally relieved his depression and appeared heartbroken when Wally was nabbed by pranksters last year. His unusual companion undoubtedly brought him joy, but he also brought social media fame.

Employers deal with requests from staff wishing to take rabbits, donkeys, pythons and peacocks into the office

In Britain, according to the Business Disability Forum, employers increasingly deal with requests from staff wishing to take everything from rabbits and donkeys to pythons and peacocks into the office. Even the courts have been affected as some people have insisted on bringing their ESAs in with them. Last year, Vincent Harvey brought his Staffordshire terrier to his sentencing for dangerous driving, only for it to defecate on the court floor. Court officials have been told that updated guidance will soon be delivered to clarify how to respond to ESA requests.

The problem is that ESAs exist in a legal grey zone. Unlike a proper assistance animal, such as a guide dog, ESAs are not trained to perform a particular role, but to provide companionship – to be a pet, in other words. Assistance animals have legal protection thanks to the Equality Act, allowing them to accompany their owners into places animals would not otherwise be allowed.

ESAs have no such protection. Employers have no obligation to allow them into workplaces. But they do have a legal duty to ensure disabled employees are not disadvantaged. If an employee claims they can’t work without bringing in their animal, they might suggest it is discrimination if the employer refuses to allow it in the office. For employers, this is an obvious minefield. Can your emotional support budgie share an office with my emotional support cat?

While there is no government register for ESAs, private organisations offer the service. For a little over £100, Support Dog UK & EU will provide an official-looking PVC ID Card, paper certificate and adjustable bandana for your dog. The same service can be provided for a variety of animals, including miniature horses, iguanas and chinchillas. ESA Registry UK, a rival, claims to have added more than 11,000 animals to its books since 2019. So many requests have been put in for GPs’ notes to prescribe workplace Fidos that some doctors are charging, even though they have no legal obligation to support an ESA claim at all.

That doctors feel obligated to do so cuts to the heart of the ESA phenomenon. Making every effort to help the mentally ill is a sign of a civilised society. But that compassion has been hijacked by those wishing to use claims of personal fragility, valid or not, to allow them to take their pets with them everywhere. It’s emotional infantilisation and it’s not healthy for the animal owners, nominally reliant on a pet’s affection to function, or indeed for the pets themselves. One colleague who recently encountered an emotional support dog described it as the most nervous-looking animal they had ever seen – an unsurprising consequence of spending its life as a living outlet for its owner’s neuroses.

A pushback against this ridiculous descent into nursery rhyme-land is required. The Equality Act should be amended to clarify that employers are under no obligation to admit ESAs and that a failure to do so should not be considered discrimination. If someone truly believes they cannot work without their pot-bellied pig in the office, they need a doctor, not a porker. Believing otherwise does a disservice to both the owners and their animals.

Comments