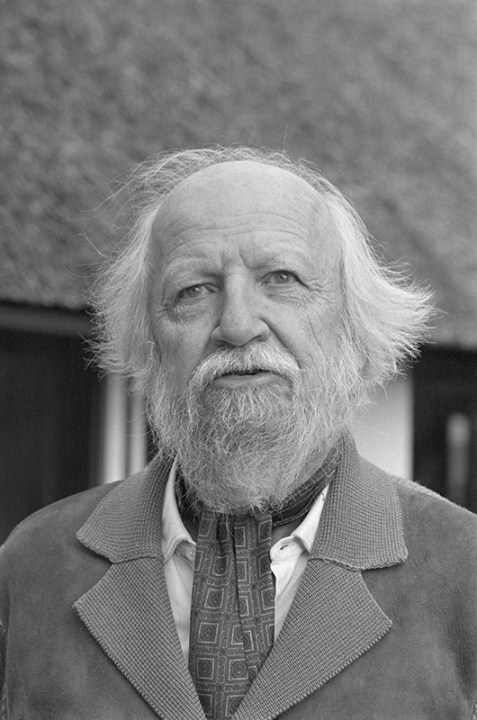

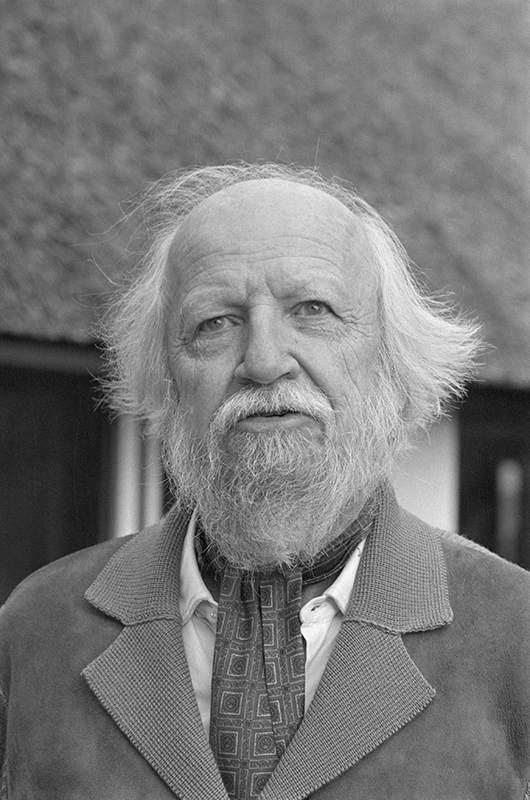

It is hard to believe that the 1983 Nobel Prize in Literature would have been awarded to the author of titles such as The Chinese Have X-Ray Eyes, Here Be Monsters or – yes – An Erection at Barchester. But if William Golding had had his way, so it might have proved. Charles Monteith, his loyal editor at Faber & Faber, saved him from himself; and thus it was that those books were called instead Pincher Martin, Darkness Visible and The Spire.

For whatever reason, Golding thought himself a monster and his journals seethed with self-disgust

Even Golding’s first and most famous novel, Lord of the Flies (1954), started life as Strangers from Within. Its publishing history is almost as well known as its plot (of boys stranded on an island turning savage). Golding, already in his forties, was a teacher and D-Day veteran who had been hawking the manuscript around various firms unsuccessfully. A reader at Faber, one Polly Perkins, had rejected it as ‘rubbish and dull’. Monteith, newly arrived at the company, could see beyond the hail of misspellings and eccentric punctuation and recommended drastic reshaping and excision. Golding eventually told Monteith: ‘I am as a writer at least partly your creation.’ Theirs was a steadfast friendship and professional partnership, cemented by Golding’s support during a vicious smear campaign to expose Monteith’s homosexuality. Their four-decade correspondence is now published as William Golding: The Faber Letters.

At first, books poured from Golding. In the decade after Lord of the Flies he wrote four novels and, admired byE.M. Forster and T.S. Eliot, swiftly became the subject of critical studies. A period of writer’s block and false starts, fuelled by alcohol and insecurity, was broken in 1979 by Darkness Visible. His magnificent sea-voyage trilogy, To the Ends of the Earth, appeared across the 1980s, about ‘men at sea who live too close to each other and too close thereby to all that is monstrous under the sun and moon’. Critical reception was mixed – particularly to The Paper Men, a damp squib of a late novel with faults to which Monteith was uncharacteristically blind. But by the time of Golding’s death in 1993, knighted, Bookered and Nobeled, he was a wealthy and bestselling literary giant.

A biography by John Carey appeared in 2009, when Golding’s readership seemed on the wane. If, as I suspect, it has since dwindled further, then that is not Golding’s fault. Lord of the Flies proves of great beauty and force when reread a decent interval after schooldays; but it is matched in invention and intensity by many of the later books, from The Inheritors, an account of a Neanderthal tribe, to The Spire, about the construction of a cathedral spire in the Middle Ages.

‘I have a streak of imagination in me,’ Golding admitted, ‘which makes it fairly easy for me to sink into a story completely.’ Research was unnecessary. That imaginative streak could conjure anything; his prose could describe anything. It was a mighty combination. A drag-rope scraping the underside of an 18th-century man-of-war; the construction sites of the Middle Ages; a German prison camp; a tropical island populated by schoolboys – his sentences can render all of these with a credibility and blaze that still astound.

Best of all, to my mind, is Darkness Visible, about a child who, emerging naked from a burning building in the London Blitz, grows up to become a scarred mystic. The novel is full of oddities or even weaknesses (Golding sent it to Monteith ‘with all its imperfections on its unkempt head’). Ill-disciplined and opaque, it is made of two apparently unrelated halves. It wanders where it will; it wrestles with terrorism, paedophilia, saints and devils. It is hard to say what it means. Golding admitted – I think without facetiousness – that he didn’t know what the ‘damn thing is about’. Yet it had to be as it had to be, and its power is stark and unignorable.

The problem is that such lumpy and imprecise terms as ‘mystic’, ‘visionary’ or ‘spiritual’ are unavoidable. Golding’s books lend themselves with unfortunate ease to what Wikipedia entries tend to describe as ‘Themes and Symbols’. A thousand school essays on Lord of the Flies have solemnly discussed its treatment of man’s capacity for evil, the loss of innocence and the possibility of redemption. PhDs will have trudged through the ‘imagery’: a child with stigmatic wounds; a cathedral spire an erection? Golding’s inspiration for the latter was the spire of Salisbury cathedral, which is of such vaulting ambition and weight that the supporting pillars bend inwards under the stress. The metaphor is irresistible: these novels threaten to buckle under the weight of all he is trying to say. But his soaring struggles can make the virtuosity of his rival Anthony Burgess seem hollow, or the perfume of Lawrence Durrell so much faded potpourri.

One early reviewer of Darkness Visible suggested that Golding ‘does not have a talent. He is possessed by a daemon’. The letters to Monteith cast some light on this possession. Golding’s was a method that hewed prose blindly out of the dark, groping towards the bigger picture as he produced ‘a mess of words to find out if there is a book in there’. He was a mire of insecurity: ‘I hate this book with a profound weariness … a load of cod’s wallop.’ Monteith would praise and soothe, and much of the editorial back-and-forth is great fun (‘We hesitated for a moment… over the words “fuck” and “fucking”’; ‘if the reader doesn’t know what “fellatio” means, that’s his bad luck’).

Carey’s biography revealed a tortured soul, unnervingly attuned to all that is monstrous. Advance publicity made much of a murky story about Golding sexually abusing an underage girl. Critics fastened on to his eventual grandiosity, his thrift, his rages. He was besotted with his wife Ann, and his tormented homosexual inclinations were seemingly consummated only in dreams and on the page. For whatever reason, Golding thought himself a monster and his journals seethed with self-disgust. But monsters do not know themselves monstrous and his awareness of an inner demon may be proof of his ultimate humanity.

Confined exclusively to the correspondence with Monteith and a handful of colleagues, The Faber Letters gives the impression that Golding was a witty, genial, vague and self-deprecating novelist who occasionally drank too much and cheerfully sent up his infamous parsimony. (‘Am obsessed with money, money, money. Am very, very vulgar.’) There is little hint that this was not the whole story, although Tim Kendall is a sedulous editor, diligently explaining dozens of literary allusions. (Just a few slip through the net: ‘Hard gemlike flame’ is Walter Pater, for instance.)

Lives are made of trivia as well as spiritual struggle, and it is refreshing to keep company with an untortured Golding as he shops for bathroom suites or tends his garden. (In the index can be found ‘rhododendrons’, ‘orchid cultivation’ and ‘tits, misunderstanding between WG and Bodley’.) But not all readers will share my unusually high tolerance for discussion of sales and royalties. And even this devotee began to tire of the thank-you-for-the-nice-weekend letters; the how-many-books-have-I-sold letters; and the I-have-removed-this-comma letters. As Golding sinks temporarily into writer’s block, the correspondence goes slack and Kendall’s present-tense commentary struggles. 1972: ‘Very little happens this year.’ 1973: ‘This year is even more uneventful than the last.’ Numerous letters are about writing that never saw the light of day, and others will mean nothing to those unfamiliar with the minor works. An appendix of synopses would have been transformative, as would a great deal more biographical information. Even Monteith’s year of birth is missing. This volume can function only as a complement to other books. It is a gifthorse with missing teeth.

I wonder whether Kendall’s devotion ought to have been lavished on a wider selection of correspondence; or, better still, an edition of Golding’s journals. Running to 2.4 million words, mostly unpublished, these may yet make Golding’s darkness visible. Until then there is simply the work, casting its long shadow like a spire.

Comments