Michael Schützer-Weissmann was the greatest teacher I ever had. When I was 17, I got into trouble at Sherborne, my school in Dorset, after a friend and I each drank a bottle of whisky. I felt splendid, but my friend had to be stomach-pumped. For that the headmaster, Robert Macnaghten, caned me. It was amazing that he managed to hit me six times, because he was famously blind — and had once awarded a detention to a coat hung on a peg at the end of his classroom, mistaking it for a boy refusing to sit down.

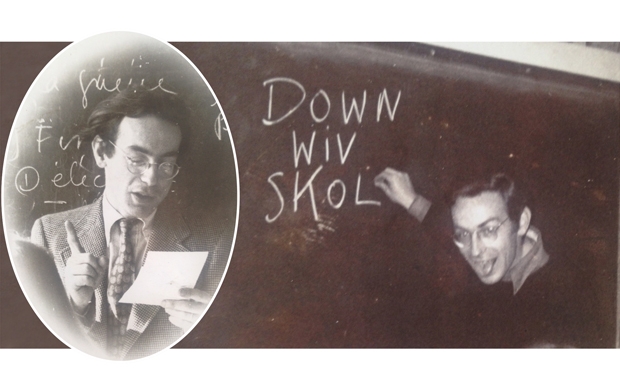

Caning probably saved me from expulsion, but I was thoroughly fed up with Sherborne: neither a ‘blood’ at rugby nor good in lessons. That’s how ‘Schutz’, as we all called him, found me. The day he walked into my English class and we opened Paradise Lost, my school life changed, as it did for the generations of boys and girls he taught. ‘He combined the scholarship of a don with a disdain for… intellectual humbug,’ recalls Richard Hudson, a master at Shrewsbury where Schutz taught for many years after Sherborne. ‘An innate respect for his fellow men – I never heard him speak ill of anyone, was… allied to a Swiftian instinct for satire.’

Schutz’s Jewish family had fled Budapest for London before the Holocaust. He grew up in Blitz-ruined West Hampstead and attended St. Quintin’s, the grammar school where –- as he enjoyed telling people — Jihadi John was later a pupil. After Cambridge he converted to Catholicism.

Schutz was a great English master whose religion never tampered with his teaching, though it burnished our appreciation of Evelyn Waugh — and even T.S. Eliot and Milton. I found him fascinating, partly because at that age I needed an exotic spiritual antidote to the dull Anglican sermons I heard under the cannonballed flags of Sherborne Abbey.

My real education began when I decided against going home in the holidays, and stayed instead with Schutz and his wife Titi. They had four children then (they ended up with 12) in a house where life took place around a large kitchen table on which was placed freshly baked bread and an open bottle of wine, the walls were covered with ars sacra, and the floors strewn with sheet music. Books were everywhere.

I wasn’t the only troubled boy cared for by Schutz and Titi. There were dozens over the years. Students frequently gathered in the kitchen talking literature, and sampling French wine. One contemporary, Simon Simpson, recalls how Schutz had to break off one session because Titi’s waters had broken with their fifth child, leaving for hospital ‘at a very relaxed pace’. Thanks to Schutz I got a place to read English at Oxford.

The author Jon Stock tells me: ‘I struggled and struggled with syntax and sentence structure throughout the fourth and fifth forms, and then, in what I can only describe as an epiphany… the penny dropped and I handed in an essay with what he described as clear and balanced sentences. It was entirely down to Schutz’s perseverance. For what it’s worth, I went on to read English at Cambridge and have written six novels.’

Schutz’s kitchen-table seminars at Sherborne found true form when he moved on to become head of English at Shrewsbury. This had been the school of Frank McEachran, the intellectual model for Hector in Alan Bennett’s The History Boys, famous for making boys stand on chairs to recite gobbets of poetry he dubbed ‘spells’. Instead of spells, Schutz founded the-‘Building Society’, a forum for senior pupils to discuss fine architecture. Although, as his invitation letters explained, ‘its embrace is not confined to building or indeed to material things…’ Pupils and teachers- presented papers on any number of topics, while ‘modest refreshments’ were provided. Once again, these were usually French wines gathered on summer holidays to the Continent, across which Schutz transported his Catholic tribe in a giant white van.

The ‘Builders’ made visits to churches and houses like Witley Court, a huge Worcestershire pile worked over by John Nash and Samuel Daukes, which burned down in 1937. Rory Fraser, a ‘Builder’ now reading English at Oxford, recalls trips were ‘made epic by the excitement of escaping campus and getting slightly pissed over lunch. Unlike school, we weren’t being treated as pupils, but rather as connoisseurs…’ Rory goes on: ‘I cannot remember a single occasion when we used a textbook in his class. He used to sit in front of us, more like a PhD student than a teacher, and read us a pre-prepared essay. Sometimes it was relevant, highlighting theological or witty angles, or it would be completely irrelevant, but very interesting… I’ll never forget finishing King Lear in his class. He was reading it, we listening. On the final page, he put the book down and stared out of the window for two minutes.’

For decades I stayed in touch with Schutz, off and on, while I lived in Africa. He met my wife Claire and they talked about him writing a film script on Milton. But teaching was his true vocation. When the time came for our children to find schools in England, Schutz persuaded us to send our daughter, Eve, and son, Rider, to Shrewsbury. We visited ‘Chateau Schutz’ and his home with Titi was just as I had remembered it. The kitchen table was for wine, talk and meals while the living room, with its grand Bechstein, was for family prayers — and end-of-year performances of his Shakespeare pastiches ‘As You Leave Us’ and ‘Lots Leave Us Lost’’.

Last June, sitting next to the artichokes in Schutz’s garden, I imagined years to come of conversations. My children — Catholics, thanks to their mother rather than me, who never quite made the jump — would be his new students. But by December, Schutz was killed by cancer. At his funeral, filled with generations of pupils, teachers, nuns and ‘Old Builders’, his coffin was borne by his six sons. Richard Hudson reckoned the occasion was uplifting rather than sad: ‘It felt like a docking procedure between Earth and Heaven.’

Comments