It’s very fashionable these days to be despondent about the quality of our politicians. They’re all lazy liars who look only to their interests and neglect their duties to their constituents because they’d rather be grunting and snorting around a trough before sticking their snouts in it. And while the expenses scandal, resignations and court cases show that a lot of anti-politics sentiment has been provoked by the politicians themselves, it’s worth remembering that not every accusation levelled at Westminster is fair.

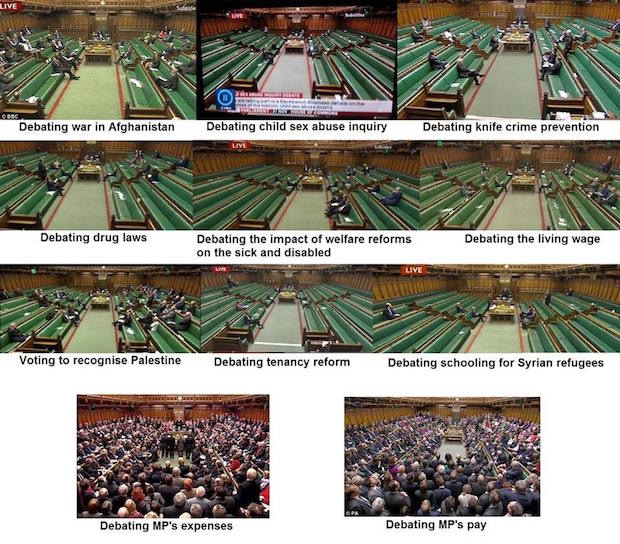

Over the past couple of years, a trend for internet memes about politicians has grown. Those graphics tend to juxtapose two images from Parliament, one showing lots of MPs apparently very interested in something, another with a handful of sleepy politicians loafing about on the Commons benches. Naturally, the first image bears a caption suggesting that MPs are debating something that benefits them personally, while the second claims they’re voting on something that affects very vulnerable people. Here’s one example.

Shocking, isn’t it? But mostly shocking that so many people have been taken in by what is a big fat lie. The bottom image claims to be from 11 July 2013. There was no debate on pay that day, which was a Thursday. There are often fewer MPs in the House on a Thursday. So this image is from the wrong day. I’ve combed the PA images archive and, surprise, surprise, it’s not from a debate about pay in 2013. It’s from Prime Minister’s Questions on 5 September 2012. Here’s that picture in slightly better quality.

Prime Minister’s Questions, 5 September 2012. Picture: PA

The top image is from a backbench debate in which a Labour MP called for a review into the impact of welfare reforms after a petition. It is poorly-attended because the debate had, by this point, been going on for a while. A screen grab from the start and close of the debate would have shown a more packed chamber. When debates go on for several hours, MPs often pop in and out as they have other business going on at the same time. They may be in a select committee, meeting constituents, taking part in a Westminster Hall debate, running an all-party parliamentary group meeting, briefing journalists, plotting a rebellion with colleagues or working in their office. They were all whipped by their respective parties to vote on this motion. But even though speaking in the debate gave MPs an opportunity to put their point of view across, it changed nothing because the type of debate meant the result of the vote was in no way binding on the government.

Here’s another image, from something called the ‘Coalition of Resistance: Can’t Pay, Won’t Pay’, which a very intelligent friend of mine shared on Facebook this morning:

Good, grief, look at how many MPs are debating their expenses! That image on the bottom left struck me as a bit strange when I zoomed in. When you’re used to looking down on the tops of MPs’ heads from the Commons press gallery, you get quite used to what Parliament looks like from above. And I didn’t recognise that Parliament. The hair looked different, frankly. I was right not to recognise it: when this debate took place, I was preparing to take my A-levels. It was 27 January 2004, when MPs voted on the Second Reading of the Higher Education Bill to introduce top-up fees. Here’s that picture in better quality from the Press Association archive.

Voting takes place in the House of Commons during the Second Reading of the Higher Education Bill on 27 January 2004 which introduces controversial university tuition fees. Picture: PA

Given university fees are still a big debate a decade later, surely even the Coalition of Resistance acolytes might be quite grateful parliamentarians bothered to turn up for that.

The next image claims to be a debate on MPs’ pay. Well, I suppose if you count MPs coming into the House of Commons on the first day of the new Parliament after the 2010 election a debate on MPs’ pay then maybe. But you can read the Hansard here, just to be sure.

A general view of the House of Commons, London, as MPs gather for the first time since the General Election on 18 May 2010. Picture: PA

The screenshots at the top of that graphic may well be more accurate. For instance, here is the video of that vote to recognise Palestine. It doesn’t show a particularly packed Chamber.

But even here it is worth remembering that this was a non-binding vote that caused a great deal of debate outside the Chamber.

I do have some sympathy for some of the frustration that people feel when they flick on BBC Parliament and do see only five sleepy MPs sitting in the Chamber apparently debating ‘the impact of welfare reform on disabled people’ or something with a very serious title like that. It immediately appears as though the politicians do not care about this very serious subject – when the reality is that this is an Opposition Day debate that makes no difference to the way the government runs its affairs or sets policy.

You might argue that, for many MPs, it is more constructive to be outside the Chamber during those sessions if they can influence government policy by scrutinising it in other ways. A select committee, for example, or writing parliamentary questions, briefing journalists on the failure of a certain policy or taking a delegation of MPs to lobby the Prime Minister. But very few people understand the different sorts of Commons business and assume that everything that takes place in the Chamber has the same import. It doesn’t.

Journalists (like me) who cover parliament don’t help if we assume that everyone knows the difference between an opposition debate and a vote on a Government bill. Or if we suggest that a Labour vote on housing benefit is a ‘crunch vote.’ Such votes can be talked up, in an effort to encourage readers to view Parliament with the same excitement and sense of drama that us strange Westminster Village hermits do.

And perhaps if trust in politicians were higher, these memes wouldn’t be shared so uncritically as people would think there was something rum about them. But I suspect that the lack of suspicion about what the graphics purport to show doesn’t just arise because MPs have let us down. It’s also because of a failure to read the internet critically (read this fascinating Demos report on trust in the internet) and a lack of knowledge about what Parliament does and how it works. These memes certainly aren’t doing any explaining, they are deceitfully spreading lies.

It is quite easy to end up writing about the problems with parliament and the failings of politicians. Our assumption tends to be that the problems with politics today lie solely in Westminster. But these memes show that mendacity is found outside SW1 as well as in it. If we must hold our politicians in revulsion – rather than recognising that they’re no more (or less) flawed than the rest of us – then we should at least also hold those who create these totally inaccurate graphics in even lower esteem.

Comments