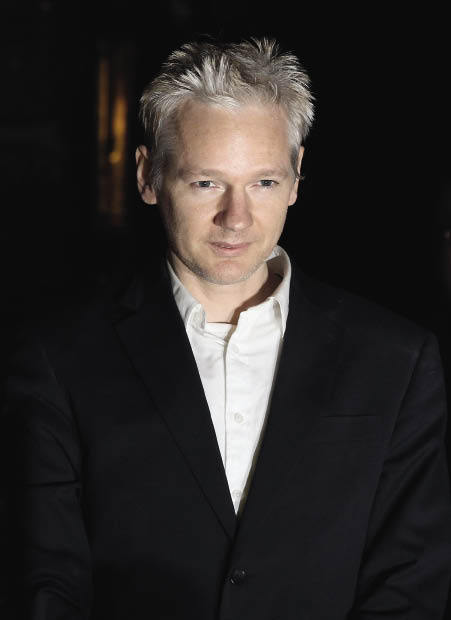

A monsoon of literature will eventually be written about the WikiLeaks story. Here are two of the first droplets. David Leigh and Luke Harding have delivered an enjoyable account of the Guardian’s fraught dealings with Julian Assange and the publication of the secret US cables. The WikiLeaks founder comes across as a shadowy, manipulative character with the habits of a tramp and the brain of a chess grandmaster. When it suited him he displayed an absurdly possessive attitude towards documents he couldn’t possibly claim legal title to.

The story is blown dramatically off course by the assault charges filed against Assange by two Swedish women last year. In Leigh and Harding’s account the allegations amount to very little. One of his accusers didn’t realise she’d been the victim of a crime until she discussed it with a friend. His offence in Swedish law (oddly translated as ‘minor rape’) carries a maximum sentence of one year, which is automatically reduced to four months in exchange for quiescent behaviour. What Assange fears is removal to the USA and an espionage trial, but given that public figures like Sarah Palin have virtually called for his assassination — ‘Why was he not pursued with the same urgency we pursued al-Qa’eda?’ she asked — an extradition would violate his human rights.

If he needs a character witness he won’t be telephoning Daniel Domscheit-Berg whose book, Inside Wikileaks, is an entertaining exposé of Assange’s career from the perspective of an early supporter. At one time the entire project consisted of Assange and Domscheit-Berg beavering away on a couple of laptops in a flat in Wiesbaden. They subtly encouraged the impression that ‘hundreds’ of associates supported them, but this was a creative reference to their Twitter fans and the geeks who logged onto their chat-room.

Domscheit-Berg, whose testimony may not be entirely reliable, paints a hilarious portrait of his former friend as a paranoid, arrogant, self-centred, workaholic hippy-rebel with a Christ-like sense of destiny. We learn that the brave exposer of cover-ups had ‘a free and easy relationship with the truth’. Assange claimed that his hair turned white at the age of 14 when a homemade ‘reactor’ in his basement started leaking gamma rays. Domscheit-Berg wryly notes that the etymology of his unusual surname has been ascribed to ‘at least ten ancestors from various corners of the globe, from the South Sea pirates to Irishmen’. The rumour that Assange is ‘a black belt in all known international martial arts’ receives this tart rebuttal: ‘His improvised shadow-boxing lasted a maximum of 20 seconds and looked extremely silly.’

Physical clumsiness seems to haunt Assange. He bumps into things. He drops dumbbells. If he broke a cup, says Domscheit-Berg, he’d blame it on the State Department. His sense of direction is so poor that he could get lost in a phone booth. But his appetite for work and his powers of concentration are astonishing: ‘He could commune with his computer screen for days on end, becoming one with it, forming a single, immoveable entity.’ Assange preferred to ‘type blind’ without checking the screen as he wrote. ‘Working without optical feedback is a kind of perfection,’ he says, ‘a victory over time,’

He usually wore ‘ski pants’ and a hooded sweatshirt but a change of mood occasionally required a new look. ‘I need a jacket,’ he once demanded. ‘I have to write a very important statement today.’ Outside the flat he liked to wear disguises. An attempt to evade surveillance by dressing as a builder in ‘a blue East German sweatshirt’ with a wooden pallet slung over his shoulder wasn’t a success. Each time he returned to the flat he conceived elaborate new diversions to baffle the spooks. But he merely baffled himself. ‘He used to walk up and down the street, looking left and right, trying to identify my front door. You couldn’t have behaved more conspicuously than Julian.’

As the fame of WikiLeaks grew, so did Assange’s capacity for jealousy and megalomania. Any suggestion that Domscheit-Berg could be considered a ‘co-founder’ of WikiLeaks infuriated him. ‘Too much personality,’ he scolded, after Domscheit-Berg gave a bland interview to a German magazine. Any challenge to Assange’s authority was met with this quasi-aphoristic put-down: ‘Don’t question leadership in a time of crisis.’ And when the Iraq war logs were released he developed a habit of flouncing out of meetings with the Gandhiesque exit-line, ‘I’ve got a war to stop.’

It’s likely that some portentous Hollywood version of the WikiLeaks saga is in development, and that either Johnny Depp or Leonardo DiCaprio is being lined up to play the lead. For my money, the story belongs to a different genre altogether. The diligent downtrodden sidekick should be played by Matt Lucas and the demented Aussie messiah by David Walliams.

Comments