Drinking in Corbières, a dingy basement bar just off St Ann’s Square, 30 years ago, you could bump into any number of groovy young Mancunians clustered round the jukebox, talking about the bands they were going to form. One night, as the jukey played ‘The Cutter’ by Echo & the Bunnymen, all evening long it seemed, there was talk of an odd duck from Stretford called Steven Morrissey. Nobody knew him but his name was in the wind.

Soon he had formed The Smiths with a guitar player, Johnny Marr, whose sweet pop sound complemented, or supplemented, his partner’s predominantly sour words. For three years the collaboration worked, so long as you felt, as many teenagers have always felt, that the world was jolly unfair, and your place in it uncertain. For those who had scrambled through their teenage years the band’s appeal was less obvious. Richard Williams, the sort of critic who gives pop journalism a good name, thought The Smiths represented the clearest possible case for the restoration of national service.

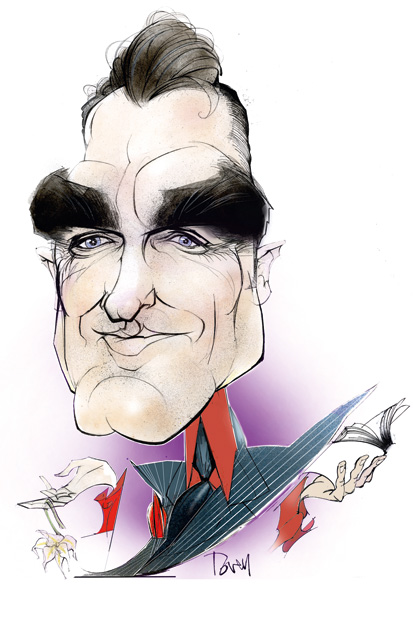

Morrissey was indeed an odd duck. The use of a surname by itself was the first clue. It seemed to say: I’m not just a pop star, I’m serious. Then there was the self-conscious dropping of literary names, starting with every troubled adolescent’s favourite spokesman, Oscar Wilde. Sometimes it is hard to realise what a remarkable man Wilde was, given that so many mediocrities have sought to summon his spirit to give flavour to their own lives.

But what made Morrissey unusual was the often clever way in which his songs incorporated other aspects of popular culture. The Smiths were not merely a pop group, they were a northern pop group, like The Beatles before them. And like The Beatles, they borrowed freely from the long-established music hall tradition that lies at the heart of working-class Lancashire life. A lyric like ‘as Antony said to Cleopatra, as he opened a crate of ale’ could fit snugly into a routine by Les Dawson or Ken Dodd. It’s an arresting image. It’s funny.

In those early days Morrissey was frequently funny, though even then there was an underlying bitterness, and a sense that the spontaneous quips had been thoroughly scripted. At times they were lifted from his favourite films, which included Billy Liar, A Taste of Honey, Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, and many of the Carry Ons. His vision of English life was never really an original one. He observed the north through the filter of writers, film-makers and jesters (George Formby being a particular favourite) who had preceded him.

Years later, after he had moved to London, Morrissey befriended Alan Bennett, who has since said that every time he popped round for a cup of tea the singer wanted to talk about Jimmy Clitheroe, a television star of the early Sixties (who wasn’t actually all that funny). No doubt the pair also chewed the cud about Housman and Auden, poets that Morrissey allegedly admires and about whom Bennett has written superbly.

In his autobiography, published at his insistence as a Penguin Classics imprint (feel free to supply your own joke), Morrissey is happy to quote other famous writers. Goethe and Gertrude Stein are in there, suited and booted, while his schooldays are, we are encouraged to believe, ‘Kafka-esque’. That would be Freddie Kafka, one imagines, who lived next door to the Morrissey family in cosy Kings Road, Stretford, while the lad was growing up. This kind of pretentiousness has been taken at face value for so long by the more credulous members of the pop media that it’s no surprise that Morrissey regards himself as an artist. One of those critics alluded in his review of the book to Eliot and Larkin. Poor chap. He probably pours sugar on his chips and salt in his tea. What the book reveals, of course, is a man blessed with candour but no self-knowledge, which is a bit of a disadvantage when writing an autobiography.

Sixties Manchester was not heaven on earth. Nor was it the Dickensian dump Morrissey would have us believe. Whores did not tout for business in leafy Stretford and as for his memories of miserable schooldays, and teachers who liked to punish miscreants, these are overgrazed pastures. But this is the picture he wants people to see, of how the forces of repression turned him into the mardy little pup who never grew up, and there was nothing he could do about it.

In three decades of unloading his misery on a world he finds too cold to take part in, few people have escaped his wrath. The royal family exists as a kind of dictatorship, judges are bent, patriotism is a joke, last year’s Olympic Games was barely a step away from a Nuremberg rally (didn’t you see those jackboots?), and the Krays, being working class, were misunderstood. And don’t forget, boys and girls: ‘meat is murder’.

This is not an iconoclast speaking. Morrissey is not a seer, or a pioneer, or a free spirit cutting through swaths of prejudice. He’s a bore, every bit as tedious as the buffer who drains a chota peg in St James’ and tells his companions the world has gone to the dogs. Shamefully Penguin fell for this ruse, and lent a spurious respectability to a mucky exercise. They must know they will never be allowed to forget it.

It is worth quoting Bennett, one of the few people of whom Morrissey approves. ‘It’s all very well never to do what is expected of you,’ he wrote in The Old Country, ‘but what do you do when the unexpected is what people have come to expect?’ Quite. Morrissey is midway through his sixth decade and, emotionally speaking, he’s still waiting for his balls to drop. You can’t help thinking it has been a sad life.

Comments