Outside of London, the area in Britain that has seen the greatest settlement of eastern Europeans since 2004 has been Kent, for obvious geographical reasons. And to cater for their needs and provide creature comforts, a multitude of shops sprang up in the years that ensued. But a strange thing has started to happen here in east Kent: all the Polish and Baltic shops are starting to close down.

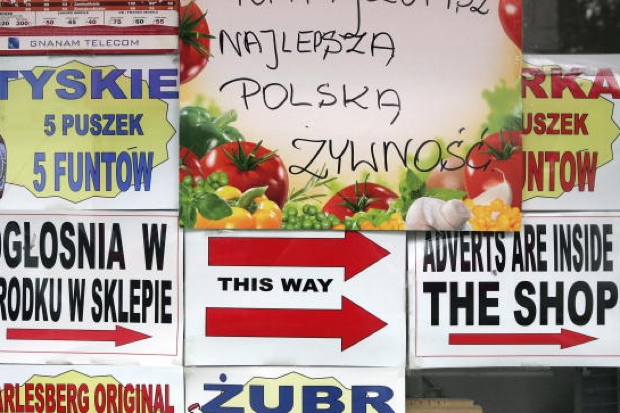

This struck me during a visit to Canterbury last week, when I noticed that the premises of the ‘East European Food’ store in Burgate Lane has now been vacated and lays empty. This represents a trend. The Polka Shop in Bench Street, Dover, has also closed this year, while its neighbour in that town, previously known as ‘The Baltic Store’, has reinvented itself as the all-purpose store, ’15 Market Square’. The Baltic Store in Ramsgate’s Queen Street has become ‘Victoria Express’ while in Ramsgate High Street another Polish shop has halved its premises (which are now a barber’s) and has renamed itself ‘International’.

Sure, you will still find Polish, Latvian and Lithuanian foods in these places, but the closing or rebranding of these shops represents a demographic shift. It signifies the beginning of the assimilation of the most recent wave of Poles who came here ten years ago. They now have bilingual children of school age, and as a consequence, have just as much contact with English parents of their children’s friends as with their countrymen. Just as the Irish ‘community’ has dissolved (even though Irish people still migrate to Britain) – so the Polish community has reached the point of dispersal. In a week in which we’ve heard much about this country becoming more ethnically divided, it’s worth keeping in mind that here in east Kent the trend is the opposite.

Go into ‘Coffee to Go’ in Cannon Street in Dover and you will hear Poles and ethnic English friends chatting and mixing (unlike more recent immigrants from the Balkans in the town, who really do live lives apart). Go to Market Square and observe the locals exchanging pleasantries with the staff as they buy their regular cans of Tyskie lager. Go to Folkestone and hear Poles and natives talking in the aisles of Iceland supermarket – and no longer as staff addressing customers. Go to the newsagents next to Argos in Ramsgate and listen to the Latvian women behind the counter calling customers ‘darling’ or ‘love’ with a Kentish-Estuary twang – somewhat archaic and ‘inappropriate’ terms that most British people would think twice before using these days. I have even overheard a Polish woman in Deal market explain to a stall holder that she was thinking of moving down here, because ‘London is becoming too crowded’. What could be a more English complaint than that?

The generation of Poles who came to Britain in the postwar era are still within living memory. I went to Catholic school in west London with many of their children – that generation born in the 1970s whose ethnicity you cannot now readily detect by their English accent or married names. And so the trend repeats itself. The Poles and Baltics who came to Britain over ten years ago in their twenties as ambitious workers have become settled British subjects and parents in their thirties. Their children are growing up as bilingual Britons with English accents. This is why they are less inclined to pine for home, for their pickles and sauerkraut, which you can get in the supermarket these days anyway. Their food, their surnames and their folk memory will be their abiding legacy.

Patrick West is a columnist for Spiked

Comments