At some point during the past decade and a half, it was decided that the 1990s were a golden age. While Britpop, New Labour and acid house do not immediately evoke the same spirit as, say, Versailles under Louis XIV or Augustan Rome, compared with what followed they were certainly characteristic of something.

Appetites for what the energetic Sawyer calls ‘the last nutty pre-internet age’ have never been greater

Members of Gen Z who have known only the colourless, anodyne first years of the new millennium speak of the Nineties in mystical tones. At a party last week, I found myself holding court over some twentysomethings who’d discovered that I am a millennial. ‘What was it really like?’ they asked, as if coming face-to-face with Shackleton or Francis Drake.

I had always supposed that I looked back on the Nineties with rose-tinted specs because it was the decade of my childhood. Listening to a new podcast Talk ’90s to Me, I am persuaded there is more to it; that the 1990s are worthy of nostalgia and deserve the envy of those who didn’t experience them.

If you’re old enough to remember a truly great decade – the 1960s, for example – this may well strike you as nuts. But just look at the streets today. Can you really blame the young for idealising an era that has only just passed out of reach?

In the tantalising summary of Irvine Welsh – interviewed in the second episode of the podcast – the Nineties was ‘that very interesting time in Britain when people just started drinking in fields and factories’. If you’ve read Trainspotting, you’ll know that he understood its dark side, too. But the programme made it sound like one endless, classless rave.

According to Welsh, the 1990s actually began in 1987 or 1988 and were the product of intuition of impending disaster. He likened us then to animals before a tsunami. The spectre of the internet, big money, sell-offs and a post-cultural world loomed before us: we were sentient to it all before it materialised. Somehow this didn’t dent our optimism and we just carried on with one final wild fling of the millennium.

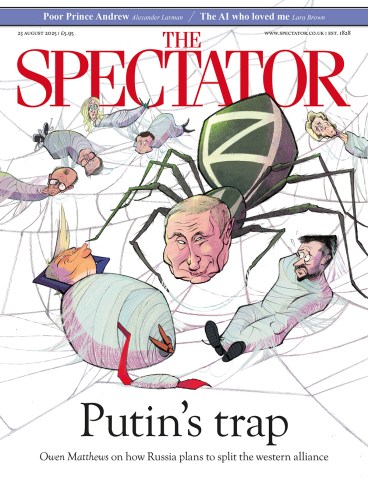

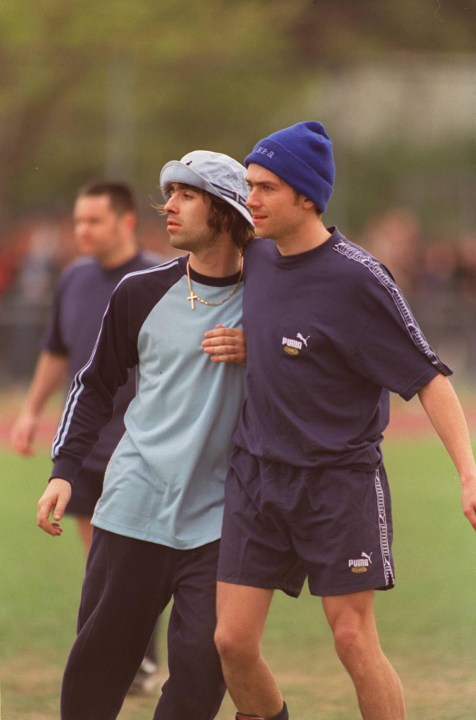

Miranda Sawyer, who hosts the podcast, awakes your nostalgia with similar ease. I’d forgotten how much people cared about things such as the rivalry between Oasis and Blur. (The resurrection of the former and obviously inferior band has contributed to Nineties nostalgia this summer.) As Sawyer chatted to Ted Kessler, formerly of NME, I had a vivid memory of the feud playing out.

The podcast is still in its infancy, with three episodes released at the time of writing, but it’s hitting the spot. Appetites for what the energetic Sawyer calls ‘the last nutty pre-internet age’ have never been greater. You can bet the episodes will find at least as many listeners among those born after 2000 as among those who knew the ecstasy-filled years before.

The differences between then and now become starkly apparent when listening to Floating Space. The podcast is devised and presented by a 25-year-old Londoner named Katie Stokes to address the problems of isolation in the modern world. More than 700,000 people in the capital admitted to suffering from severe loneliness last year. The closure of facilities and the convenience of the internet have played a part in hastening our withdrawal from public spaces. What humans need, says Stokes, is ‘a third place’.

The concept comes from an American sociologist named Ray Oldenburg. Writing in 1989, he stressed that, away from home and work, we should seek a third place in which to socialise and simply exist in the times between. The idea appeals to Stokes, who works remotely full-time and misses the ‘small-town’ network she knew growing up outside of London.

Wistful for something like Central Perk in Friends, that bastion of Nineties living, she trials a different place each week. Will the gym prove more sociable than online? Is there still a nightclub scene? Are private members’ clubs as stuffy as assumed? The drawback to sampling one place per episode is that it provides each institution with an opportunity for self-promotion. It is monotonous to have the manager of a club talk about how his club is different from all other clubs. Stokes is, though, balanced in her assessments and a conscientious host.

Her mission to reprise Oldenburg’s advice is also admirable even if progress is difficult to achieve. By the end, I wondered if we wouldn’t all be better off shunning the gyms and clubs, and running, dancing, for the fields.

Comments