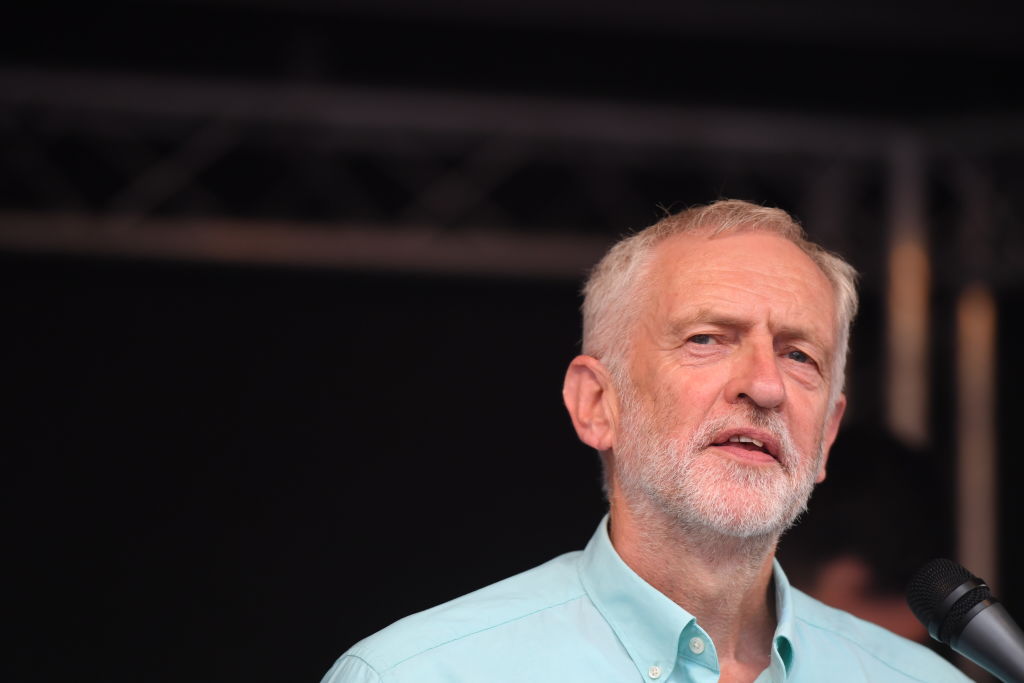

This week, The Sun instructed Remain Conservative MPs to unite behind Boris Johnson or see Jeremy Corbyn’s desire to ‘turn Britain into an experiment in 21st century Marxism’ become reality. It need not have bothered: the threat of a ‘Marxist’ Corbyn government is one of the few things about which all Conservatives agree. But what kind of a threat does Corbyn really pose?

Keen supporters of the Labour leader speak of their hopes for a ‘transformative’ Corbyn-led government, one that will eventually lead to socialism. This government will permanently change Britain because, they say, it will disperse power to the people. Under John McDonnell’s plans, industries will be renationalised but run differently than in the past: communities and employees will help manage them.

At the heart of the Corbynite vision is the idea that Labour’s members will be – indeed are in the process of becoming – the basis for a ‘social movement’. Instead of just being concerned to get people to vote for the party, this social movement will engage with and empower communities in new ways, infusing them with radical ideas to encourage ordinary people to take on the establishment on council estates and the workplace.

Corbynites believe a Labour government will need such a movement, one composed of millions, if it is to survive inevitable attacks from the capitalist enemy. As the authors of the excellent Corbynite primer ‘People Get Ready!’ write, a transformative government needs ‘both an informed, empowered, and strategically aware party membership, and a strong ecosystem of social movements outside the party’.

With that in mind, Labour has set aside £3 million to employ community organisers whose aim is to build this movement. But there are only 38 of them. If a social movement is to develop it will be largely due to the work of volunteers within the party, and especially Momentum – the self-proclaimed ‘people-powered’ organisation created in 2015 to advance Corbynism.

To some, Momentum is the ultimate Marxist sect, composed of swivel-eyed hipsters, avocado on toast in one hand and a copy of Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks in the other. This may be true in certain parts of London. But what about elsewhere?

I recently met with a Momentum group in a suburban borough of Greater Manchester where Labour did especially well in the 2019 local elections. About ten members were present and hipsters there were none, most being in their 40s and 50s and a few older; they were what the Daily Mail might look upon as a very respectable group, happily sharing a lemon drizzle cake over a pint in a quiet working men’s club.

One present – probably in his 70s – even criticised Corbyn and had nice things to say about David Owen. He claimed that if only Owen had stayed in the party in 1981 he would have become leader. Not everybody agreed with that sentiment.

There was, however, a consensus that Momentum had hardly started building a social movement in the borough. Some complained how little influence they had within their local Labour parties because so few of their own number wanted to be involved in the nitty-gritty of party affairs. I got the impression that the battle against the power-hungry Labour Right – as they saw their opponents – was what consumed them: they didn’t have much energy left for engaging with society.

Across Britain, Momentum branches have worked with the homeless, asylum seekers, women’s and youth groups as well as food banks, but with only 40,000 claimed members (and possibly less) it has hardly built even the foundations of a movement adequate to sustaining a transformative Corbyn government.

The organisation has been invaluable in entrenching Corbyn’s authority in the Labour party, in the last NEC elections helping elect all nine of his supporters, meaning he now controls that vital body. But only one-third of Labour members voted in those elections: if so many cannot be bothered to do even that, how few are prepared for the truly arduous task of building a social movement? What’s more, Labour party membership is now in decline; from a post 2017-election peak of 550,000, it is possibly down 20 per cent or more.

There may well be a Corbyn government in the near future – the First Past the Post system has produced a few odd results in its time. But it will likely lack a Commons majority and in any case be dependent on the support of many Labour MPs who owe more loyalty to Tom Watson than Corbyn. Such a government might be able to reverse some of the austerity policies introduced after 2010. But any weakness in Westminster will not be compensated by a strong social movement in the country: that simply does not exist.

This doesn’t mean that, so far as Conservatives are concerned, Corbyn couldn’t still do some damage. But they thought that of nice Ed Miliband in 2015 – and even Tony Blair back in 1997. So those fired up by hysterical claims of Corbyn turning Britain into a new Venezuela, might want to calm down a bit.

Steven Fielding is professor of political history at the University of Nottingham and is writing ‘The Labour Party: from Callaghan to Corbyn’ for Polity Press, to be published in 2021

Comments