According to popular imagination, the skies over Britain have been full these past few months of fleets of private jets carrying their non-dom owners to fiscally safer climes. According to your point of view, this has either rid the country of parasites or denied us investment and trickle-down wealth. Two glossy reports pumped out by financial companies in the past month seemed to promote the idea and were immediately leapt upon by those who oppose the abolition of non-dom status.

First, there was the UBS Global Wealth Report 2024, which predicted that the number of dollar millionaires living in Britain will plunge by 17 per cent between 2023 and 2028. Then Henley and Partners, which helps the rich shift themselves and their piles of money around the world, published its Private Wealth Migration Report, making a similar sort of claim. During 2024, it claimed, Britain will lose a net 9,500 dollar millionaires, more than any country other than China. The company launched its report with an opinion piece opening with an anecdote of a billionaire who ‘promptly loaded himself and family on to the private jet – presumably vowing never to return’.

But is it true that the wealthy are leaving Britain? There is – to my knowledge – no official publicly accessible register of personal wealth in Britain, and if there were few of us would get anything done, as we would be too busy looking up our friends, exes, neighbours and celebrities. What we do have are HMRC’s published figures for the number of non-doms resident in Britain. While they don’t quite cover the same thing – wealthy UK citizens fleeing the country wouldn’t show up in these statistics – they appear to tell a different story to the UBS and Henley reports. Any non-doms who have left the country have been more than compensated-for by new arrivals. Last year, there were 83,800 non-doms, up 6 per cent on 2022. Over the course of the year, 12,900 new non-doms either settled in Britain or claimed the status for the first time – this despite the growing inevitability of a government which had promised to abolish non-dom status.

The non-exodus of non-doms would appear to be confirmed by the property market. Who is better placed to know whether wealthy people are really fleeing Britain than the upmarket estate agents who trade in prime London property?

California has shown it is possible to drain even the world’s most successful economy of its lifeblood

‘Wealthy people are not fleeing the country in droves,’ Stuart Bailey of Knight Frank told me. ‘Our clients do not just live in Britain for the tax benefit. One told me the other day, “I choose where to base myself not on tax but on where I want to live.”’

I also contacted Trevor Abrahamsohn of Glentree Estates, whose patch includes the Bishops Avenue in Highgate, playground of the super-rich. He was keen to tell me that the abolition of non-dom status was going to be a disaster, but when pressed he admitted that he hasn’t been asked to dispose of a single property by a non-dom who is fleeing the country. He did, however, say he knew of cases of wealthy individuals who had chosen to base themselves abroad while leaving their families in London because they liked the schools and cultural life. Under tax rules, they can still spend 90 days at a time in Britain while remaining resident somewhere else in the world.

A closer reading of the UBS and Henley reports hardly suggests that Britain is losing devastating numbers of wealthy individuals. The Henley report refers to ‘millionaires’ – which it defines as people who have more than $1 million worth of ‘liquid, investible wealth’. Being a millionaire, needless to say, isn’t quite what it used to be, even if this definition excludes the value of non-liquid assets such as property. It means even less when expressed in dollar terms (you only need £780,000 in your bank account or share portfolio to qualify). According to the data behind the Henley report, there are 602,500 such people in Britain, so even if we did lose 9,500 of them it would only equate to around 1.5 per cent of the total.

But here is where it gets interesting. I asked Henley for its methodology, and it pointed me to a South African-based data analyst, Andrew Amoils of New World Wealth. He claims to have a global database of 150,000 high-net-worth individuals –a rather creepy-sounding latter-day Domesday Book. It isn’t anything like a comprehensive index but it is weighted towards a particular kind of wealthy individual: people who were involved in business start-ups. Fifty per cent of the sample, according to Amoils, have founded companies. In other words, these aren’t any old millionaires – they are entrepreneurs.

If Britain is losing entrepreneurs, even fairly modest numbers of them, then that is serious, because they are the ones who create jobs and whose growing businesses will account for tax revenues in years to come. Britain will not be a great deal poorer if it loses a few playboys and actresses, but it will miss genuine entrepreneurs.

While it might be tempting to blame a loss of entrepreneurial types on the arrival of a Labour government, the reality is somewhat different. The drop in dollar millionaires on Amoils’s database long pre-dates the threat of higher taxes under Labour. It also pre-dates the Brexit referendum by nearly a decade. The number of dollar millionaires – as defined by Henley – living in Britain peaked in 2007 at 708,500; since then we have lost one in seven of them. What constitutes a dollar millionaire has not been adjusted for inflation (nor for exchange rate), so the figure is even more dramatic than it might at first appear.

It ought to be added that while Britain stands out for the sharp loss of millionaires in recent years, their number has fallen from a high base. Even now, Britain still has the fifth highest number of millionaires in the world, after the US, China, Germany and Japan. We used to be particularly good at creating, attracting and retaining millionaires; we are a lot less good now.

Why the fall after 2007? ‘The biggest factor is the IT boom,’ says Amoils. ‘The US has dominated that, along with Asia. Canada has benefited a little, while Europe and the UK have been left out.’

The decline of the FTSE has been a big factor, he adds. Wealth creators are just not choosing to grow their companies in Britain. Company IPOs (initial public offerings) have virtually dried up – there were just 22 in 2022 and 14 last year, compared with 90 and 132 respectively in the US. For a country which once had the largest stock market in the world, it is a huge comedown.

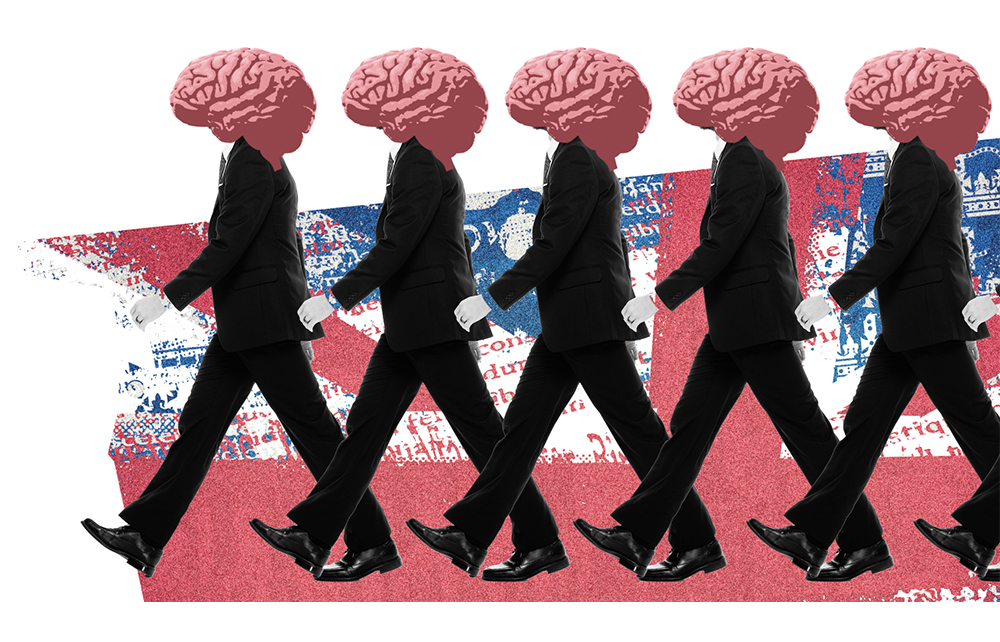

In obsessing about non-doms, we are looking down the wrong end of the telescope. It isn’t tax exiles Britain is short of, but wealth creators – not necessarily billionaires, who are always going to be tiny in number, but people growing businesses from scratch. The root of the problem is not so much high taxes or Brexit – it is the financial environment. London has become a much less appealing place to raise capital for growing businesses.

Data provided by Henley and its like provide a partial picture of Britain’s brain drain, but it is hard to get a more comprehensive one, because of the remarkable lopsidedness of official migration data. We know from the Office for National Statistics that last year 98,000 UK citizens left Britain with the intention of staying away long-term; but we don’t know what age they are, what level of education they had, how much they earned before they left and so on. There is a world of difference between a 65-year-old leaving Britain to retire to the Costa del Sol and a 25-year-old leaving Britain to follow a profession or set up a business overseas. The former group has inevitably diminished since Brexit, as it is harder to win the right for residency now, but what of the latter group: is that number going up or down? Unfortunately, official statistics give us little idea – although incomplete data such as that presented by Henley can help fill the gap to some extent.

A lot will depend on Rachel Reeves’s first Budget. If the government wants to retain talent, it is going to have to address some of the longer-term issues behind Britain’s decline as a magnet for wealth and talent – above all the eclipse of the City after the financial crisis and the poorer environment for raising business capital which has followed.

In California, governor Gavin Newsom has shown that it is possible to drain even the world’s most fantastically successful economy of its lifeblood. Nothing symbolised the state’s decline so much as Elon Musk’s decision to shift his SpaceX business to Texas. Starmer should look to California as an example of how not to treat entrepreneurs – as well as thinking about how Britain can benefit from the fallout. The abolition of non-dom status won’t help, but the real reasons for Britain’s brain drain lie elsewhere.

Comments