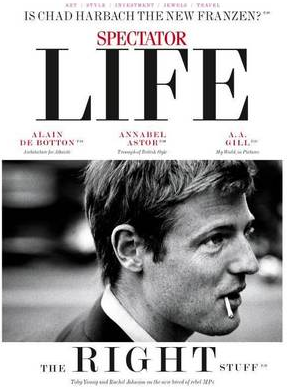

There’s a new member of The Spectator family, and she’s

called Spectator Life. This is our new quarterly magazine focusing all the more civilised aspects of life — the arts, culture, travel, etc — and it comes bundled in, for free,

with the main magazine. The first issue is available on newsstands this week, but, so you can try before you buy, here is one of its more political articles: an overview of the new generation of

Tory rebels, by Toby Young.

The Unwhippables, Toby Young, Spectator Life, Spring 2012

On the night of the great Tory rebellion over Europe, David Cameron had good reason to think that Zac Goldsmith wouldn’t join in. The Prime Minister had just made him ‘climate change and forest envoy’, a task almost tailor-made to suit the young MP’s passions. Surely he wouldn’t jeopardise that? But join them he did. Zac ranked among the ‘Glorious 81’ Tories who defied a three-line whip and voted for an EU referendum on 24 October 2011, one of the largest Tory rebellions in history. Normally, rebel MPs are mavericks or losers, the hasbeens and the never-going-to-bes. But that night 49 newly elected MPs decided to commit what is normally an act of career suicide. A new type of politics had been born.

This must have come as a rude shock to the Prime Minister, who was boasting about his new crop of MPs even before the election. The ‘A-list’ was his invention, intended to cherry-pick ‘Cameroonian’ candidates. But instead of a group of bland loyalists, trotting out the party line as soon as it arrives on their BlackBerries, Cameron has ended up with a collection of free-thinkers. According to research carried out by the University of Nottingham, there were rebellions in 179 of the 331 votes held in parliament between the election and last Christmas. That’s a defiance ratio of 43 per cent, quite without precedent in the postwar era.

Philip Cowley, the Nottingham professor who conducted the research, has various theories as to why the 2010 intake are such a fractious bunch. Normally, MPs feel duty-bound to honour the manifesto on which they stood — but the coalition agreement has ideas that many Lib Dems and Tories never signed up to. Then there’s what Cowley calls ‘the Norman Baker factor’ — the fact that plum government jobs that would normally go to loyal servants of the Tory party have been given to second-rate Lib Dems. With so little hope of promotion, exacerbated by a lack of reshuffles, why would any ambitious new MP toe the line?

Dan Hannan, the influential Eurosceptic MEP, thinks a major part of the problem is the decline in the whips’ power of patronage, and not just the lack of government jobs. Members of select committees used to be party appointees, but a procedural change at the beginning of this parliament means they’re now elected by their fellow MPs. In addition, the whips can no longer dangle tempting freebies in front of the troops. ‘They used to be able to hand out foreign junkets, but these days who has the time to go off to Fiji?’ says Hannan. ‘In the wake of the expenses scandal, who would dare?’

Dominic Raab, one of the most accomplished of the new rebels, also sees a link between the independence of the new intake and the 2009 scandal. ‘The last election was ghastly on the doorstep, with people accusing us of all being the same, of never keeping our promises,’ he says. ‘I think it brought home to all of us that in order to regain the public trust we have to puncture the impression that we’re just a bunch of lackeys and lickspittles.’

The view that the new intake feel obliged to pay more than lip-service to their constituents is echoed by Douglas Carswell, the Conservative MP who played a pivotal role in last year’s EU rebellion. ‘After the vote, several people phoned me up and asked how I managed to pull it off,’ he says. ‘Look, we didn’t plot it in a basement in Westminster. It was 81 MPs responding to pressure from their constituents. I don’t have magical, charming persuasive powers. The pressure is coming from where it should, from the voters.’

Carswell is evangelical about this shift in power and thinks it’s part of a larger trend whereby parliament is beginning to recover its voice. He even singles out John Bercow, the Speaker, as an unlikely hero of this new moment in parliamentary history: the rebel’s friend. ‘He’s not biased in a political sense at all, but he is biased in that he puts the interests of the House of Commons ahead of those of the whips,’ he says. ‘His politics are not mine, but in terms of getting parliament off its knees and restoring purpose to the House of Commons, he’s a force for good and I’m a big fan.’

Almost all the 2010 rebels cite the internet — and social media in particular — as a key reason for their new approach. Not only does it enable vast numbers of their constituents to communicate with them directly, leaving them in no doubt about how they’d like them to vote, it also means they can communicate directly with the public, bypassing the need to go via a Central Office handler.

‘I’m a huge user of Twitter,’ says Louise Mensch, one of the most internet-savvy of the new intake. ‘The great thing about social media is that it provides an unfiltered form for MPs to talk to people directly. There’s no barrier between them and you. It’s also a conversation. People can challenge you, interact with you, and they end up feeling much more engaged.’

Mensch exemplifies one of the biggest reasons the class of 2010 are less beholden to the party machine than their predecessors, which is that they’ve discovered a way of carving out a

parliamentary career for themselves outside of government. Through their mastery of digital media, they’ve managed to push various campaign issues to the top of the news agenda, catapulting

themselves into the spotlight at the same time. This isn’t just true of Conservatives, it’s also true of some new Labour MPs as well — Stella Creasy, for instance, whom The

Spectator named Campaigner

of the Year in 2011.

The Spectator commissioned YouGov-Cambridge to find out how popular these new MPs are and, not surprisingly, they easily outstrip their parties. On the Conservative side, Priti Patel, Louise Mensch and Zac Goldsmith all get higher approval ratings than their party or their party leader, as do Chukka Ummuna, Tristram Hunt and Luciana Berger on the Labour side. It is a moot point as to whether the MPs need the parties more than parties need these celebrity MPs. In the YouGov study, Boris Johnson emerges as the most popular ‘brand’ in British politics — far more popular in London than the Tory party. Without Boris, it is hard to think how the Tories would have any hope of hanging on to City Hall in the mayoral elections.

‘I love the challenge of being an MP,’ says Rory Stewart, who’s become a regular foreign affairs pundit on Newsnight in spite of being a recently arrived backbencher. ‘One

of the things that’s so interesting about being a politician today is the challenge of trying to think through what a member of parliament is and how you’re supposed to do that job.

It’s potentially the most exciting, important

job on earth.’

For David Cameron, this is a bittersweet success. He wanted to nurture a new breed of MPs. He succeeded perhaps too well: his new Twitter-literate army does not stand and wait for its orders. As a result the chamber is more colourful, less predictable and more dangerous for the government. This will send more than the occasional shiver down the Prime Ministerial spine. But it will do plenty to restore the battered image of the House of Commons.

Comments