John Bell, the former Regius Professor of Medicine at Oxford, was interviewed on today’s episode of the Today programme podcast. The following conversation with the BBC’s Nick Robinson has been edited for length and clarity.

You’ve heard tell of the NHS problems for quite a long time. Let’s just go to the headline facts and some of the things that we know are coming out. Is the NHS underfunded, John?

So I think it is not underfunded. To be honest I think we need to get better at using the money that’s in it. It’s really interesting because if you go back to the Derek Wanless days, we did run a health care-service, which for many of my early years when I was a practicing physician, was profoundly underfunded and the outcomes weren’t bad. It was very cheap and cheerful. But then over the last five to ten years, we’ve been pumping up the amount of money going into the NHS. So when you look at it as a comparator, as a percent of GDP, we actually spend more money than Spain, we spend more money than Japan, we spend more money than a lot of developed economies that have healthcare systems that deliver much better outcomes. So we’ve got a problem. We’re not the most expensive health care system. Fortunately the Americans will always have the gold medal. But we’re in the middle now. We’re not at the bottom end in what’s being spent. We’ve got actually quite a lot of money in the health system. And this might surprise people because austerity did squeeze spending on the NHS.

But then they buckled, didn’t they?

They did. Simon Stevens, of course, was a master at squeezing money out of the government. He was the chief executive, and he was good at saying, ‘hey, guys, this is all going to fall over: I need another £20 billion or whatever’. The number was £10 billion, mostly. So the numbers went up. The King’s Fund has done some nice analyses of this, where they look at all the countries as a percent of GDP, and the UK used to be way over to the right, halfway down the list. It’s not anymore. It’s kind of right in the pack. And you know, the examples I’ve given you, Spain’s got a very good healthcare system and they spend less money per GDP. So the answer is not, in my view, pouring more money or indeed pouring more people into the system. The productivity of the NHS has fallen off a cliff, and the more people we put into the system, the worse the productivity is.

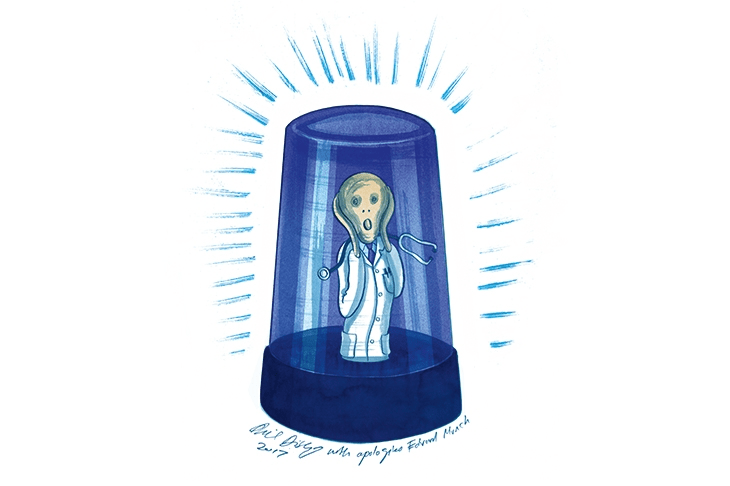

I think one of the problems is that we haven’t really modified or adapted the way we deliver healthcare since the original model in the 1950s. So the healthcare model was designed originally to take people who are symptomatic at the end stage of their diseases, prop them up a bit, make them feel comfortable, off you go, and then they die. If you look at what we’ve delivered in the time that I’ve been a doctor, which isn’t that long, we’ve delivered dramatic improvements in health care and extended life expectancy by 11 or 12 years. Well, I mean, just think about that comment: extended life expectancy by 11 or 12 years, that’s like sending a man to the moon four times over. It’s massive. Now, along with that has come the problem of how you deal with the multiple complex chronic diseases that people accumulate when they get to be my age and beyond. By the time you get to 80, and to be clear, I’m not 80, but by the time you get to 80, most people have about four major chronic diseases. They’ve all got to be managed. People have to look after them. We haven’t really adopted the old system, which was lots of flashing lights and doctors with defibrillators and everybody dashed around in pyjamas and it was all fine. Now you go to the A&E department, you’ve got a lot of frail elderly people, they’ve got multiple diseases. It’s a complicated problem. So actually revving up productivity is not going to be easily done by just piling more pounds.

I was just digging out those figures as you were talking. They really are stark. Since 2019, NHS spending has increased by over 19 per cent. NHS staffing has increased by 23 per cent, but the number of patients starting treatment has increased by just 3 per cent.

If you were any kind of an economist, you looked at those numbers, and you go, uh-oh, got a problem here?

One of the things that happened is, in this model of looking after sick people at the end of the stage of their disease, you build a lot of hospital capabilities and you put into place specialist care. So you’ve got specialists in eyes and ears and noses and all the other bits. You build up what is actually quite an impressive array of facilities for end stage disease. And that’s what the hospitals do. I think the conundrum is if you want to do anything but the old model, are you going to really take money away from those guys to give it to somebody else? And the answer is that will be quite hard, because if you take money out of that, then, you know, when granddad gets prostate cancer, he’s not going to get treated properly. And people are going to go, hang on a minute, how does that work? That is a fixed cost, and I don’t think it’s very flexible.

The other bit, of course, is what’s been going on in the community. The number of primary care doctors has not been increasing. It’s been shrinking, unlike the acute sector. And they’re really not able to cope again because of the same demographic change, because a lot of the frail elderly, before they end up in hospital, they put it onto the GP four times and then before you know it, they are swarmed. So the system hasn’t really developed any demand management capabilities, which I think is one of the fundamental problems, because if you just let it roll on and we continue to extend life expectancy, but we all accumulate all these diseases, we’re stuffed.

The traditional demand management technique in Britain was the waiting list. Back in the 1980s, you manage demand by making people wait so long that they either give up, or crudely die.

It’s an interesting challenge to run a single-payer, state funded health care system in the modern world

It’s an interesting challenge to run a single-payer, state funded health care system in the modern world because, historically we’ve given people multiple mountain ranges to cross if they wanted to get to care. So they’d have to wait for the GP and then they’d finally be seen. Then there’d be a letter to the hospital. Somebody would lose the letter. They didn’t fuss too much about that. You know, by the end you get an appointment, you go in, you see it, you know, it will go on and on and on and on. And then in the end, somebody might do something. But now, because the burden of disease has increased so much because of that demographic change, it’s now reached a bit of a crisis point. So things are starting to fall over. So there are two models: crank the handle faster, which is, I think, the model that many people would argue you need to do. My view is that’s really hard, because as you throw more people in to crank the handle, the efficiency of the system just falls away. And it’s true with all kinds of organisations. Big companies are very inefficient because they have too many people. How do you manage that workforce in a sensible way? Some people say let’s train an extra 20,000 doctors. And I just said, well, you know, it’s like sending more guys into the battle of the Somme. You’re not going to get any more ground. You’re just throwing more people into a system that doesn’t work. My personal view is that is not the model. You’ve got to have changing roles. People have to do differently. We have to move things to the community, try and keep things out of hospital wherever we can, and use a whole range of innovations to do that.

In fairness to Wes Streeting, the health secretary, he’s talked about shifting from cure to prevention and moving from hospitals to communities. I just want to push you a bit, John, on this. You can’t crank the handle. You can’t just pour in more doctors because people might just think, well hold on, there’s a set level of demand. And then we get back to where we were. The Blair government, which inherited quite a big problem when it came to backlogs, managed pretty much to clear it over a period. Why can’t that be done?

There’s an acute reason why it can’t be done. In the midst of all the expansion of the workforce and activity in hospitals, we’ve forgotten about capital expenditure. So there’s a massive backlog in terms of hospitals and hospital beds. There are hospitals falling over all over the country, and somebody’s going to have to fix that. The previous PFI scheme was not a very good scheme. The idea of actually having the private sector fund a bit of so it’s off balance sheet was not a bad idea.

Remind people: PFI was the private finance initiative, Gordon Brown basically getting companies to build. And it ended up, sometimes with hospitals being built, with the borrowing being off-balance sheet with the private sector, but sometimes with them charging £472 to change a light bulb..

It was badly managed. If you look at things, for example, all these pathways, they require diagnostics at the front end. The truth is, if you look at the OECD, we have the least number of scanners of MRI scans, CT scans. We have the tiniest number of the bits of kit. You need to take the first step to look after people. If you want to crank the handle faster, you can’t do it without the bits of kit. Better diagnostics, better lab facilities, better radiology facilities, and better and bigger hospitals.

This is very much in people’s thoughts because of the Princess of Wales video. I was lucky enough to be treated for cancer and as it were, get over it. Catch it early, as they did with her. But lots don’t catch it early because there aren’t the scanners or the appointments.

I think that is ultimately the answer to the cancer problem: it is early diagnosis. Let’s be clear, 50 per cent of people with cancer arrive in the emergency room with a massive lump somewhere with stage four disease. And then you’re looking at very large expenditure to extend life a very short period of time.

So there are some things that we need to shift the way we think about these things fundamentally: to say, look, we’ve got to accept that 80 per cent of the time somebody has a disease, they are asymptomatic. If you take coronary disease, the thing that leads to heart attacks: most people start on that journey in their 30s and they’re accumulating atherosclerotic plaques. They feel fine. They can, in fact, go kick the football around with their kids. And it’s all fine. But the disease is progressing until at the age of 60, they go, ‘ah, I’ve got a chest pain’, then you’re in trouble. Then you’ve got to say, oh, we better do a triple vessel bypass and prop this up and prop that up. And chances are, if they’ve got it in their heart, they’ve always got it in their head and they’ve got it everywhere else. So the only way to fix that is to say, okay, let’s just think about the 35-year-old. What do we need to do to make sure that we flatten that curve by approaching them and thinking about what we can do for them? And then that’s demand management. Now, it doesn’t mean that they will live forever, you know? Something will catch them in the end, but you will get those really important, high-quality years in your 70s and your 80s, which is, I think, what we should, we should be ambitious for. And I think we should.

We’re getting to the level of public spending that things are starting to squeak

We have, I think, over many years, debated the importance of a mixed model of funding of health care. And of course, it’s been pioneered by many European countries where there is a combination of insurance policies which are covered by employers or individuals, which are mixed with a state funded system. And in some countries they work amazingly well. They interestingly, spend a bit more as a percent of GDP on health care, but they don’t spend a lot more. It’s just the burden on the taxpayer is significantly less. And I think we’re getting to the level of public spending that things are starting to squeak. And I’m not sure you can continue to ask the taxpayer to pay for all this stuff. Let me take the prevention agenda as an example. Do you think that big employers might, for a reasonable per capita, some Netflix-type model, like to cover their workforce with a prevention strategy that would give them the statins when they needed them, make sure their blood pressure get measured, get the obesity medications if they need them, and as a result, keep the workforce fit and healthy and in work longer? I’ll bet you they’ll want to do that.

Let me ask you a very specific question. What about saying if you book a GP appointment, you need to hand over your card details. They’ll take a fiver from you. And if you don’t turn up, it costs you a fiver. Yeah. It’s fine.

I think the real issue is the administrative cost of it, which is why others have rejected it.

To what extent can technology and artificial intelligence help reduce those costs?

I’m a bit of an optimist about how the technology revolution could change things. But don’t try and use AI when none of the data is hooked up to each other. I went to my GP the other day and he said, ‘oh well, you need this test’. I said, ‘well, I just had that test at the hospital’ and he said, ‘well, I can’t see it, so I’m going to stick you again.’ I kept thinking, what in the world is going on here? We’ve got to have a single integrated data system where everybody’s data is in the same pot. People can see it. They know what the GP said, they know what the specialist said and all that stuff. That’s what AI is for. And an AI will help you do that. But the fundamentals won’t work unless you’ve got interoperability of the basic data sets.

I think people in the NHS are going, oh my God, we’ve got to change this

To be clear, I don’t spend my spare time reading the King’s Speech, but there was a piece in there about having a common data framework for the whole country, because one of the issues that we have at the moment is nobody knows quite who owns the data. So the GP says, ‘well, I own the data’. And then the hospital said, ‘well, no, I own the data’. And and the NHS said, ‘well, we think we own the data’ and that is a real problem because getting the data hooked up means you’ve got to get all the data owners to say, actually, we’re going to have a single system now and we’ll have one owner, who I think is the NHS. My personal view is there are two people who own all our data. It’s the NHS, the umbrella organisation and me. So don’t tell me I don’t own my own healthcare data. That’s my data, for goodness sake.

In Covid, they introduced a thing called a copy notice, which is for emergency public health crises, in which they say no one owns the data. It’s all the NHS’s data. And suddenly we had the best data in the world. Every country in the world would turn to us to find out how the vaccines worked, how the testing worked. This was all because NHS data was amazing, and then at the end they took the copy notice away. So we went right back to where we started.

Can Wes Streeting get these reforms through?

I hope he can. Hope is a is a marvellous thing and we all need it.

But can reform of the NHS actually happen?

I think people in the NHS are going, oh my God, we’ve got to change this. That dissatisfaction is coming out in the polls. People are saying, I love the NHS, but I’m now really not very happy with it. So I think the momentum to do something bold is there. It won’t be without without difficulties because you never do something bold without difficulties. But I think it’s never been better positioned for a big dramatic step which they could take.

I’m not a member of the BMA, so I can say this, but I mean, there is a problem that the incumbents, who are the doctors in the BMA, have been a major drag on reform of health care. And that’s not just here, it’s in America. They have a massively powerful lobby in America that makes it very difficult to change the way everything because of course they do what they do that’s there. They don’t want to do something different. They were trained to do something and they don’t want to do something different, even though it might be the right thing to do. So I do think if you’re thinking about eggs, you’re going to have to break a few. I’m afraid the stranglehold that the medical profession is broadly to have on the way we run a health care system is going to have to be sorted.

What’s an example?

So there was a new drug developed for lowering people’s cholesterol called inclisiran. And it’s a very novel drug because it’s like a gene therapy, but it stops the gene that produces one of the proteins. That creates a lot of cholesterol. And what’s really nice about it is you can get an injection and it lowers your cholesterol by 50 per cent for a year. You don’t need to remember to take the statin tablets. Well, it turns out that only 30 per cent of people who get prescribed statins take them. There was a deal done with the company who made it. It was called the Medicines Company that the NHS would get it because the NHS did. A lot of the trials would get it at an absolutely bargain basement price the cheapest ever. And the NHS got very excited and said we’re going to roll out doses of this to 700,000 people in the first year, and we’re going to get to several million people after a couple of years. And it got to the GPs and they said, ‘sorry, guys, we’re not going to do this’. Why? Well, they’re not getting paid enough for the injection that they were going to give and they blocked it absolutely in its tracks. So that is in my view, not helpful. In fact, in my view it’s pretty disgraceful.

Comments