Television and film are popular mediums. Poetry has never been popular. This is Sam Weller’s father in Pickwick Papers, when he discovers his son writing a valentine, alarmed it might be poetry:

Poetry’s unnat’tral; no man ever talked poetry ’cept a beadle on boxin’ day, or Warren’s blackin’, or Rowland’s oil, or some o’ them low fellows; never let yourself down to talk poetry, my boy.

In 1994, I made a short film about Kipling. The director, Tony Cash, a man with a first-class Oxford degree in Russian, objected to a two-second reference to Aristotle’s ‘pity and terror’ in my script. ‘If you mention Aristotle, they [the TV audience] will think you’re an arsehole or an idiot.’ Until then, I didn’t realise Channel 4 viewers had such a strong antipathy to Aristotle.

Poetry has to be sold to the viewer. So biography, anecdote, the lives of the poets, tends to replace the words on the page – what you might call the Vasari ploy. A problem only occurs when poets have dull lives at the desk. It’s better if Dylan Thomas is dying of drink, or Philip Larkin is drinking half a bottle of sherry before he sets out for work at the Brynmor Jones Library and juggling three sexual partners simultaneously. Better still if Ted Hughes is exerting his force field of eroticism. No wonder an Arena documentary should begin, cynically enough, with this prefatory voiceover: ‘More controversy and scandal attaches to his name than that of anyone with the exception of Byron.’ Hughes’s best biographer, Elaine Feinstein, modified this, belatedly: ‘All these women have fallen into his grip and he’s destroyed them, but as soon as you look at the facts, it wasn’t quite like that.’

Biography and anecdote tend to replace the words on the page – what you might call the Vasari ploy

Sometimes, of course, the life is redacted. A recent TV documentary of Derek Mahon, filmed while he was alive, cooperating and concealing, made no mention of his alcoholism. A Voices & Visions

documentary about Elizabeth Bishop, made in 1988, was strangely protective by current standards. Mary McCarthy assures us that Bishop loved Robert Lowell. There is mention of her long-term partner Lota de Macedo Soares, but no mention of Bishop’s lesbianism or Lota’s suicide – let alone the rather long list of other same-sex lovers – presumably because her last partner and literary executor, Alice Methfessel, would have withheld permission to quote. Bishop exerting her veto beyond the grave. She was a very private person.

There are other limitations. In TV documentary, you have to write to the pictures, so there is sometimes dead wood dictated by availability of illustration. In Adam Low’s film about T.S. Eliot, the Eliot estate released a ‘scoop’, the scrapbooks Eliot kept after his second marriage, detailing their daily doings, theatre visits, meals eaten out and so forth. Dull, dutiful close-ups. Directors are nervous about expertise. They interview everyone at length and are then forced to ditch most of the footage because every interviewee has to be included. (Joseph Brodsky is preserved pretentiously telling us that Robert Frost’s description of a woodpile seen against the snow is like a poem on a blank page. Ah yes, that old untruth – that poetry is always about poetry.)

The medium therefore doesn’t favour focus, or sustained argument, rather a torpid consensus. I remember refusing to discuss T.S. Eliot’s anti-Semitism because time constraints would make intricate argument impossible. But I was coaxed into defending Eliot at length, with reservations. And of course, that part of my contribution never made the final cut. Instead, Eliot’s anti-Semitism was taken as proved and the crucial question asked, how would this affect his reputation?

Against these reservations are the images of the poets. Auden’s fissured face slick with sweat, his smudged lips, a damp cigarette dark with internal bleeding. Bearded Berryman in Ryan’s pub in Dublin looking like Ben Gunn, using his middle finger to halt the slide of his heavy horn-rimmed spectacles – a figure for his intoxication. Now and then, an interviewee will make a unique contribution. Fay Weldon worked at the same advertising agency as Assia Wevill, the partner who displaced Sylvia Plath and also committed suicide. They were having lunch when Assia thought she saw the dead Sylvia. She was haunted. Fay Weldon said Assia felt, not guilt, but fury that Sylvia had ruined her relationship with Ted.

Occasionally, given more time, a documentary can succeed. Bob Geldof’s exemplary A Fanatic Heart takes two hours to tell the life of Yeats. It solves the problem of the mass audience by recruiting Bono, Sting, Colin Farrell, Dominic West, Tom Hollander to read the poems. Geldof’s argument: Yeats favoured ‘a modern, plural, open, generous country’. He advocated peace. Geldof includes a telling anecdote: Patrick Pearse is ranting the usual republican polemic, citing Emmet and Wolfe Tone. Yeats asks the audience who would be prepared to die for Ireland. One person holds up his hand and everybody laughs. For Geldof, Irish nationalism summons the closed mind of North Korea. The biographer Roy Foster is at hand to amplify and modify Geldof’s views, but it is Geldof’s programme, reeking of his personality: ‘You can die for a cause, but you can live for a reason.’ He hates the idea of the blood sacrifice.

There are wonderful snippets of unbuttoned candour. He asks Edna O’Brien: ‘Would you just swoon and shag him?’ Answer: ‘Probably yes.’ He accounts for Yeats’s support for Maud Gonne’s extremism: ‘I’m with you all the way, Maud. Now can we shag?’ When Yeats at 31 loses his virginity – ‘No more wanking!’ – to Olivia Shakespear, the initiation is a disaster.

In film, biography supplants the poetry even more. Manuel Basoalto’s Neruda (2014) describes Neruda’s flight from president Gonzalez Videla. For the most part, an illustrated itinerary as Neruda escapes pursuit over the Andes: a road movie, then a room movie, then a pony-trekking movie. There are flashbacks of the young Neruda losing his virginity, reading the poetry of Rimbaud, and ignoring a denunciation of poetry as ‘a faggot thing’. There is no conflict, so no interest. The baddies are baddies. We see beautiful logs at a sawmill and so forth – landscape posing for the camera. Poetry depends on pretext. Neruda is given a false passport and an identity as an ornithologist. This provokes a sudden influx of poetry like an airbag: ‘I have always dreamed to be a bird… A condor. That black monk that dominates from the height of his bloody kingdom. Or eagle. Swelling its chest and throwing itself into the void to go through the valleys and fly over the rivers of Chile.’ It doesn’t get any better.

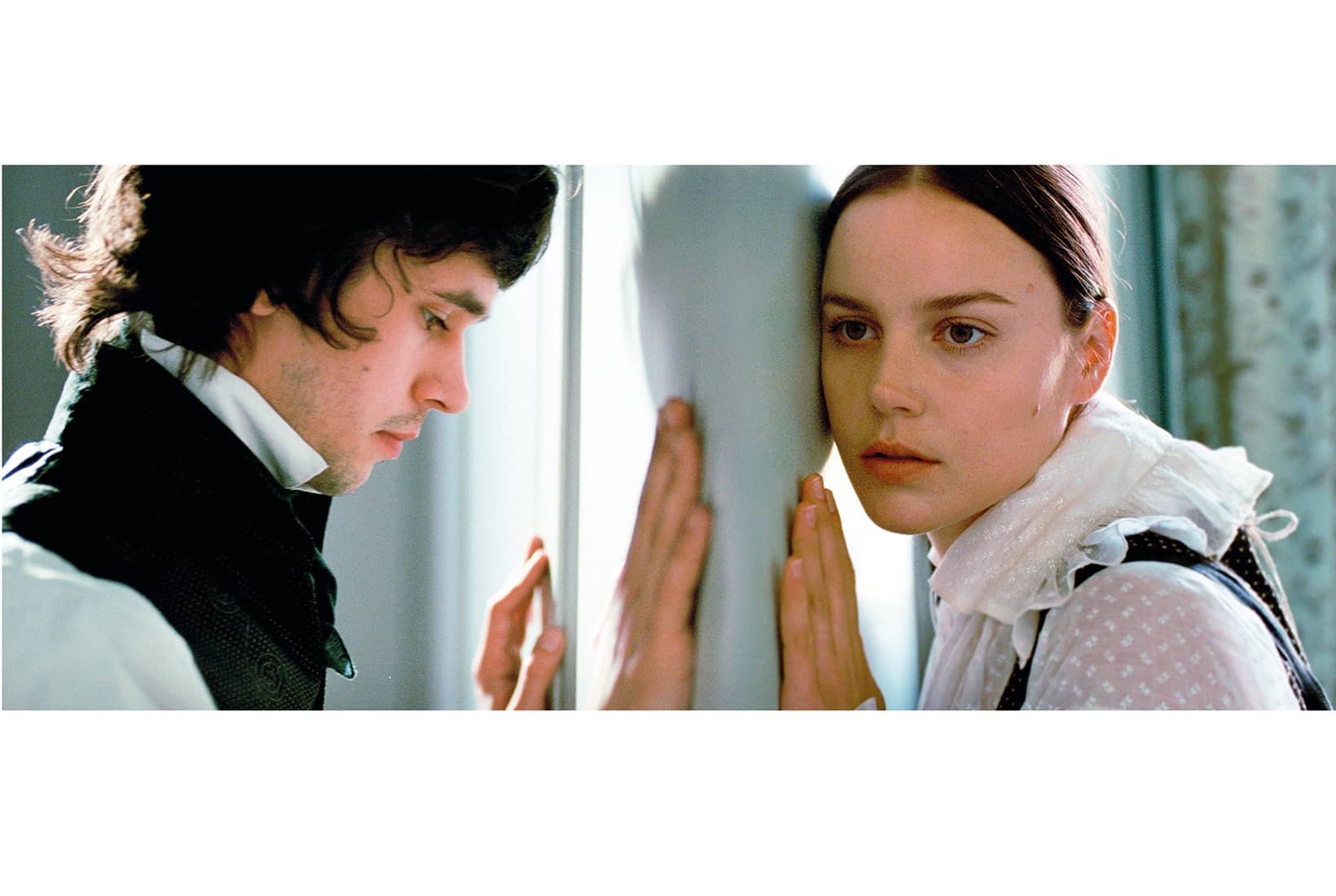

Jane Campion’s film about Keats, Bright Star (2009), has its moments. Fanny Brawne’s young sister, Toots, says of Tom Keats’s sick room: ‘I want to leave because it smells.’ She buys a copy of ‘Endymion’ so that her sister Fanny can see whether he’s ‘an idiot or not’. At a Christmas dinner, she asks Keats for a poem – ‘a short one’. Again, there is some beautiful photography, a sustained motif of bare trees, and some delicate, suggestive close-ups, particularly of yarn threading a needle. Keats and Fanny Brawne didn’t have sex, but there are some yearning approximations. Both push their beds up against a separating wall. ‘You know,’ Fanny says, ‘I would do anything.’ Keats replies: ‘I have a conscience.’ At another point, Keats fantasises that, when they are married, he will kiss ‘your breasts, your arms, your waist’. Fanny adds: ‘Everywhere.’

The problem with the movie is that the script isn’t quite true to the difficulties of the relationship. Keats was petulant, jealous, unreasonable and insecure, but the momentum of the movie can’t help succumbing to the saccharine template, a great love lost to consumption. True, we see Keats pissed off about Suitcase Brown’s valentine to Fanny. And we see him collapsed under a hedge, feverishly asking Fanny if she has a clear conscience, but neither incident has any heft. Ben Whishaw is beautiful, Abbie Cornish also, and their looks dissolve the difficulties.

Terence Davies’s A Quiet Passion portrays Emily Dickinson as a modern feminist, independent, outspoken, iconoclastic (she smashes a plate when her father complains it is dirty), spiky, unbiddable. There are frank conversations about sex. Dickinson’s sister-in-law says: ‘In truth, the thought of men in that particular respect, turned me to stone’; ‘I do my duty.’ Against this updating is the cinematography and the stilted script delivery – the convention that there was no elision in the 19th century: ‘do not’ is never contracted to ‘don’t’, and so on. The cinematography has the quality of the photographic still – flat, frontal oblongs like postcards. No trickery, deliberately austere – and rather boring to look at. As for Dickinson’s poetry, it isn’t easy – and that’s a problem. As it always is.

Benediction, Terence Davies’s biopic of Siegfried Sassoon, reviewed by Deborah Ross, is in cinemas now.

Comments