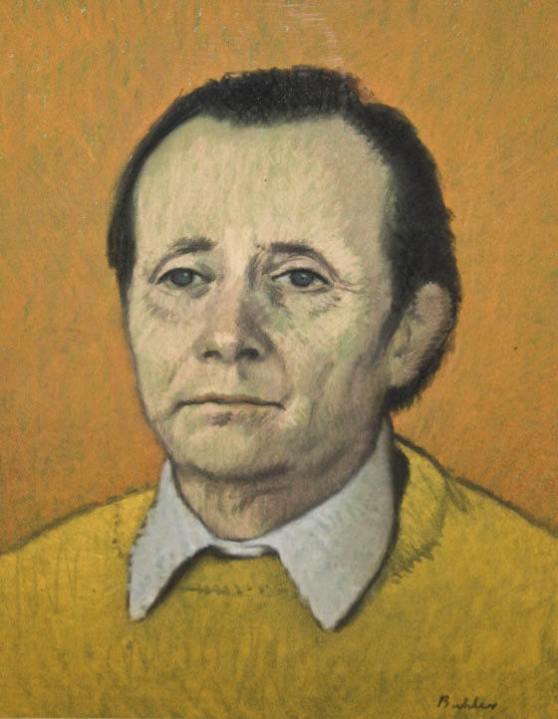

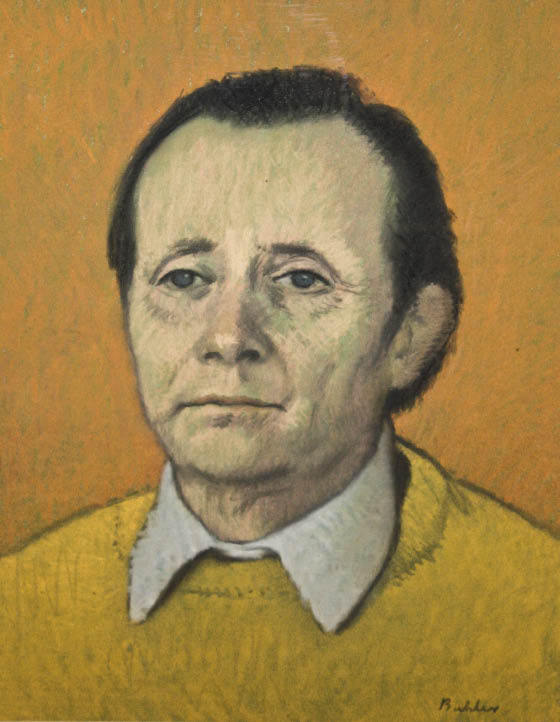

Some years ago now I bought from the artist Robert Buhler a pastel portrait of the composer Lennox Berkeley (reproduced above). Since I knew neither of the two men well (although in the case of each I admired the work without having an irresistible enthusiasm for it), even today people often ask me why I made the purchase. The answer is that in that one work Buhler shows so much more than his usual blithe accomplishment; he is perfect not merely in his portrayal of his sitter’s outward features but also in conveying an inner character of brooding spirituality.

Tony Scotland’s book performs the same feat. He miraculously catches a face as narrow and delicate as one the composer’s beautiful songs, and at the same time vividly projects a character haunted by the shadows of the illegitimacy that deprived him of an earldom, and by the the quest for a sexual satisfaction in constant conflict with the insistent demands of the Roman Catholic Church.

Until his mid-forties, when he finally married, Berkeley devoted so much time to the pursuit of the ideal male partner that it is astonishing that his final musical legacy was one of 226 works. Scotland divides this period of feverish musical and sexual activity into three parts. Firstly, in the mid-twenties, there is Oxford, then full of elegantly effeminate girl-boys, many later to marry, like Evelyn Waugh, and produce large broods of all too often neglected and demanding children. There follows Paris, centred on the Place de la Madeleine — described, with some exaggeration, by the painter Jean Hugo as ‘the crossroad of destiny, the cradle of loves, the matrix of disputes, the navel of Paris’.

When not making friends with the ‘wild hornets’ of the city’s modernistic composers, taking classes with Nadia Boulanger, her grave, cerebral muse perhaps of less value to him than some classes with another friend, Aaron Copeland, might have been, or drinking cocoa from Guadeloupe in some seedy boîte, he slaved away at his compositions. There are also visits to Maugham’s Villa Mauresque, with a lot of skittish behaviour already familiar to readers of biographies of the Master by Selina Hastings and Jeffrey Meyers.

Then the second world war is about to break out. Berkeley has a number of liaisons, the most fervent with Benjamin Britten, who eventually brushes him off as he leaves for the United States with Auden. Berkeley is endlessly forgiving to the better composer and was repaid, as was Britten’s way, with coolness, contempt and bile.

Soon, the war out of the way, Berkeley will settle down, now in his mid-forties, to a happy, albeit absurdly protective, marriage to Freda. As Scotland puts it:

He needed not only a mother, but a secretary, a cook, a nurse and a housekeeper, possibly even a wife. Whether he knew it or not, he needed Freda.

The marriage between Lennox and Freda was a happy one, as was that between another purposeful, intelligent and robust woman Natasha Litvin and the poet Stephen Spender. In each case, many of the husband’s former cronies mocked at this sudden choice of domesticity. I remember well the occasion when I told one of Lennox’s homosexual friends, just back from abroad, of the marriage: ‘Oh, so she got him at last!’ The tone was gratingly unpleasant.

Scotland writes at length and in general skilfully of the years of bachelor freedom. I can only wish that he had brought the same deliberation and skill to writing about the marriage. From what I saw of it, it was clear from the start that Freda’s competence, affection and high spirits ensured that she, Lennox and the children all lived contented lives. She was, like Natasha Spender, a woman who all too clearly preferred the company of homosexual men to that of heterosexual ones. Yes, of course, she was the dominant partner; but that was precisely what ensured that the match did not disintegrate. Scotland’s is a highly informative and psychologically persuasive study. But he has missed the opportunity to produce something even more interesting — an account of the sort of marriage that may sometimes lead to misery but may also lead to far more happiness than many people realise.

Comments