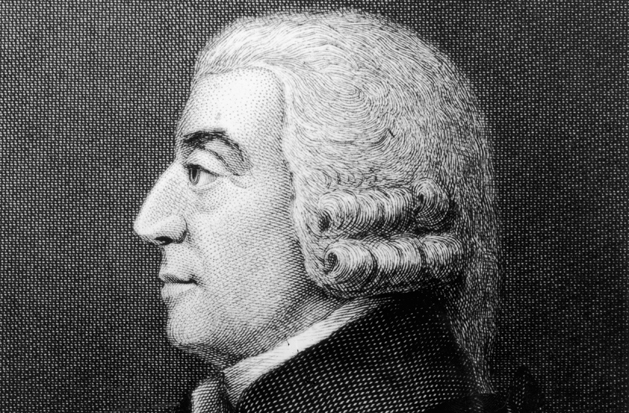

Adam Smith’s theory on the division of labour first appeared in 1776 in The Wealth of Nations. The idea was later revived by The Coasters in their early 1960s B-side ‘My Baby Comes to Me’.

Well, she go to see the baker when she wants some cake

She go to see the butcher when she wants a steak

She go to see the doctor when she’s got a cold

She go to see the gypsy when she wants her fortune told

But when she wants good loving my baby comes to me

When she wants good loving my baby comes to me.

As Mr McClinton explains, rather than dividing his efforts between the supply of cake and fortune-telling, the baker is better off concentrating on the former. Similarly, the doctor will be better off not diversifying into the provision of ‘good loving’, leaving that market niche to the narrator, who seems to enjoy a healthy competitive advantage.

What is interesting about the division of labour is not just that it works, but that it works in many different ways. At the most basic, it arises from the simple insight that ten people each concentrating on one task will do a better job than ten people dividing their time between ten different tasks. But it also works elsewhere. For instance a butcher will be able to stock a greater range of meats if his shop is not cluttered up with cakes.

It also works at the level of trust and reputation. A fishmonger suffers more damage from selling poor fish than a general retailer. We therefore trust them not to do it badly. Would you buy oysters from a cake shop?

Consumers seem to understand the benefits of specialisation instinctively. When I see a restaurant which advertises ‘Thai food and tapas’ I do not think ‘What an excitingly diverse eating experience’ but ‘Hmmm, probably a rubbish restaurant’.

So the interesting thing about the division of labour is that it isn’t really all about labour. It’s also about the division of attention, the division of reputation, the division of expectation and the division of trust.

(The only exception to this law seems to be ‘Timpson’s Paradox’, the peculiar economic discovery that, for no readily discernible reason, key-cutting and shoe repair must always be performed at the same location.)

But perhaps the most important effect of the division of labour is the division of attention, and the effect this has on innovation. If you spend 5 per cent of your time screwing legs on chairs, it’s not worth inventing an electric screwdriver. If you spend 100 per cent of your time screwing legs on chairs, you dream about nothing else.

Oddly, Adam Smith noticed this effect, and included it in an early draft of The Wealth of Nations. But then he deleted it.

It was the division of labour which probably gave occasion to the invention of the greater part of those machines, by which labour is so much facilitated and abridged. When the whole force of the mind is directed to one particular object, as in consequence of the division of labour it must be, the mind is more likely to discover the easiest methods of attaining that object than when its attention is dissipated among a great variety of things.

The reason this is important is that it is now widely believed that innovation itself takes place in specialist clusters: in Silicon Valley, or in university departments. Much of it does. But much innovation still comes from people in a trade. As Smith goes on to say, ‘He was probably a farmer who first invented the original, rude form of the plough.’

Comments