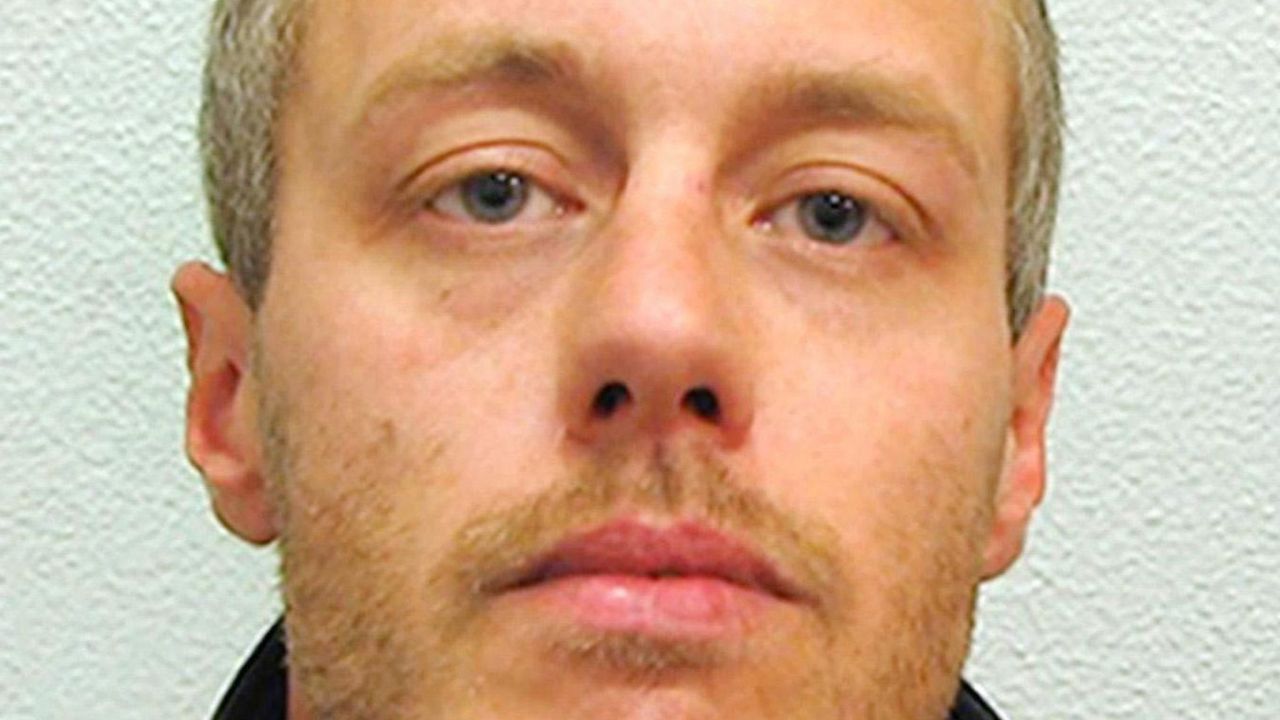

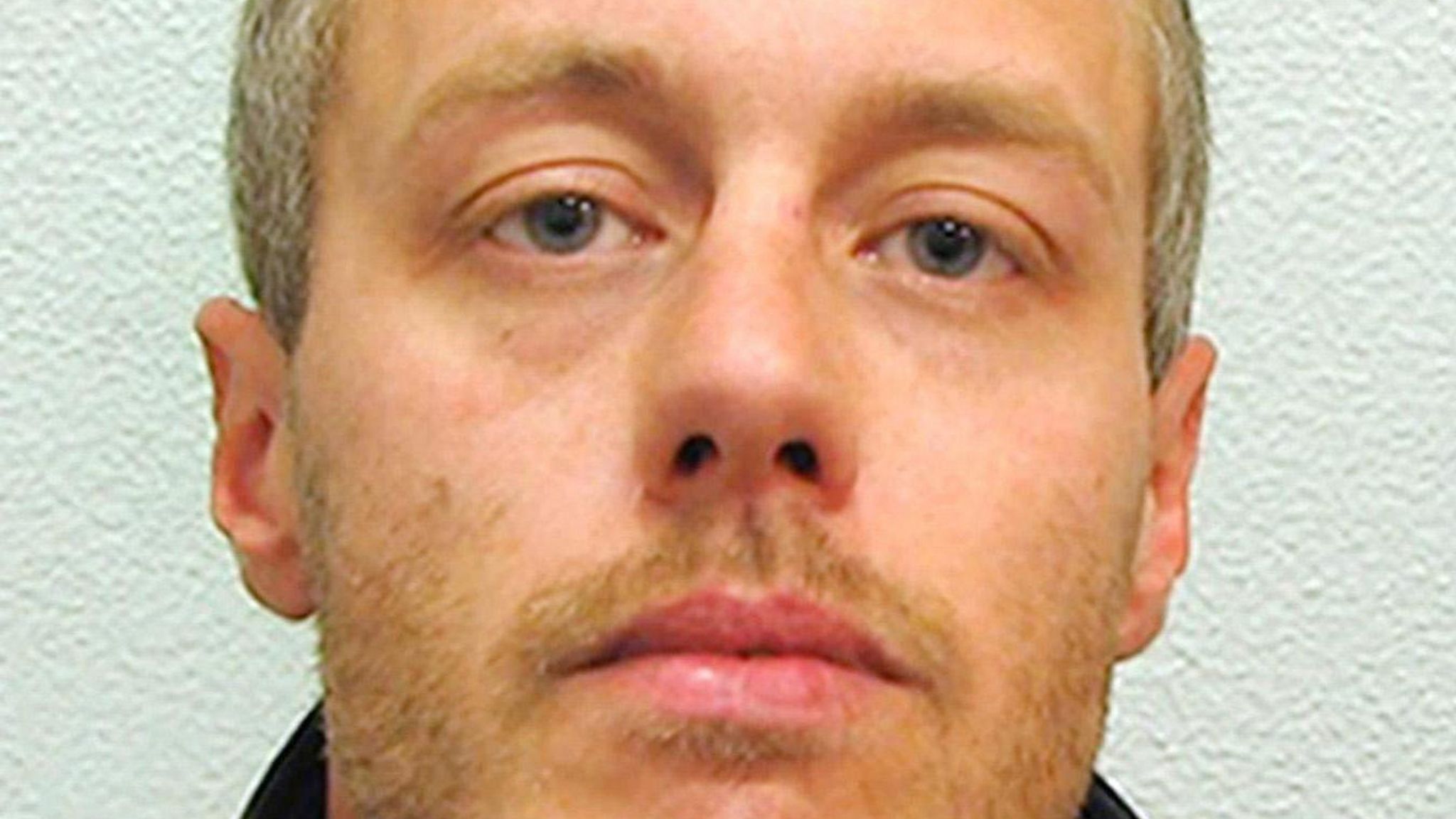

David Norris, one of the men who murdered the black teenager Stephen Lawrence, had his parole hearing this week, but he was so uncomfortable about being seen that those watching on a videolink only ever saw the back of his head. They did, however, learn a lot about what goes on inside it – and why Norris is nowhere near ready for release from prison. The two days of evidence also highlighted an alarming disparity between the attention given to a criminal bidding for freedom and the victims he left behind.

The parole system is still geared towards the needs of offenders, with a pathway to rehabilitation and release for those serving long sentences

The Parole Board agreed to hold Norris’s parole review in public. It was his first attempt at securing his release since being jailed for life in 2012. Including time spent on remand, he has served over 15 years in custody, nine months more than the minimum term ordered by the trial judge. The proceedings, which were taking place in a prison, were relayed onto two television screens set up in a courtroom at the Royal Courts of Justice so that Stephen’s relatives, as well as journalists, were able to watch.

The cameras at the prison filmed the hearing from two positions. One displayed a front-on shot of the three-person Parole Board panel which was presiding over the case; the other showed the panel sitting across a white table from Norris, who could be seen only from behind. This represented something of a compromise after the 49-year-old had unsuccessfully pushed for a private hearing, claiming that to hold it in public would lead to ‘sensationalised’ coverage, ‘increase’ the risk to his safety and cause him ‘additional emotional stress’.

But not being able to see Norris’s face – only the back of his dark shirt and the closely-cropped grey hair on the back of his head – heightened the sense that he wasn’t being entirely honest and couldn’t be trusted. Although he admitted his involvement in Stephen’s fatal stabbing in April 1993, the first of the attackers to do so publicly, he said it would put him and his family at risk if he were to reveal the names of the others and tell the ‘whole truth’. Of the six gang members believed to have been involved, three are still free and liable to prosecution should there ever be enough evidence. (One suspect has died; Gary Dobson is the only other one to have been convicted).

Norris’s account about what had happened on that night in south-east London was inconsistent, details about his upbringing were incomplete and he appeared to over-state the progress he had made in custody after being a ‘horrible, violent and racist young kid’. A prison psychologist, who interviewed the convicted killer for nine hours, said he was an ‘unreliable narrator of his own life’, partly because he was deliberately trying to ‘re-write history’. Another psychologist, instructed by Norris, said there may be a degree of ‘minimisation’ in relation to incidents he was involved in, while he had provided a ‘more sanitised’ version of his early life with a ‘physically abusive’ father who humiliated him. It reminds me of the case of the ‘black cab rapist’ John Worboys, who carefully crafted a version of events around his offending which helped convince the Parole Board to sanction his release from prison in 2018. Fortunately, the High Court saw through the deception and overturned the decision.

I do not expect the Parole Board members determining Norris’s fate to be as gullible as Worboys’ parole panel was. For a start, the organisation has strengthened its procedures since then – the questioning of Norris, the psychologists and the prison and probation staff who had worked with him reflected that: it was impressively detailed and forensic. Only one of the five witnesses recommended that he should be freed. And although the question as to whether he is safe to be released does not turn entirely on his honesty, consistency and openness it will surely form an important part of the parole panel’s deliberations.

Norris’s unwillingness to name the other men who carried out the murder is particularly troubling because it suggests he still fails to appreciate how important it is for Stephen’s loved ones to obtain justice. Five years ago, legislation was introduced to deal with cases in which convicted killers refuse to divulge where their victim’s body is. It was known as ‘Helen’s Law’, after Helen McCourt, an insurance clerk from Merseyside, who was murdered in 1988 by Ian Simms. He never revealed where he’d buried Helen – but was freed from prison nonetheless. The law was changed so that the Parole Board is now obliged to consider a prisoner’s failure to disclose the location of a victim’s remains when assessing their suitability for release. There’s a strong argument to say that the law should also apply to prisoners who blatantly fail to cooperate with police in the way that Norris has done.

Yet, the parole system is still geared towards the needs of offenders, with a pathway to rehabilitation and release for those serving long sentences. Almost half of the 6,811 prisoners whose cases were heard at an oral hearing in England and Wales last year were freed. Having observed several hearings, including Norris’s, it’s clear that huge effort goes into putting in place a prison regime which helps inmates address the causes of their offending behaviour so that they can lead more productive lives on the outside.

There are sound moral, practical and financial reasons why that is the case, but it stands in stark contrast to the glaring absence of support for victims of crime. Over the past two years, report after report has highlighted the gaps. An inspection by three watchdogs for the police, probation and the Crown Prosecution Service said provision for victims was undermined by high workloads, competing demands, poor communication and a lack of skills and knowledge. Last year, the Victims’ Commissioner, Baroness Newlove, said the findings of a major survey of victims she had commissioned showed many were ‘left guessing’ about the status of their case and felt like an ‘afterthought’. At times it appears as though the criminal justice system bends over backwards to accommodate life sentence prisoners while ignoring victims who have their own life sentence to endure.

At Norris’s hearing, a clear sign of the imbalance came on the second day when the prison psychologist suggested that the jailed murderer may have been suffering from ‘trauma’ because of the crime he had committed 32 years ago. ‘I regularly see people traumatised by their own actions,’ he said. I can only imagine what Stephen’s mother, Doreen Lawrence, who was watching the video feed, thought of that.

Later this month, a prison officer will deliver a brown envelope to David Norris with a letter from the Parole Board setting out its decision. It will be a shock – and an outrage – if it agrees to set him free, but he will get another shot at parole in two years’ time and, if unsuccessful then, a further go two years after that. And so on. For the bereaved, however, there is never any prospect of release from their suffering.

Comments