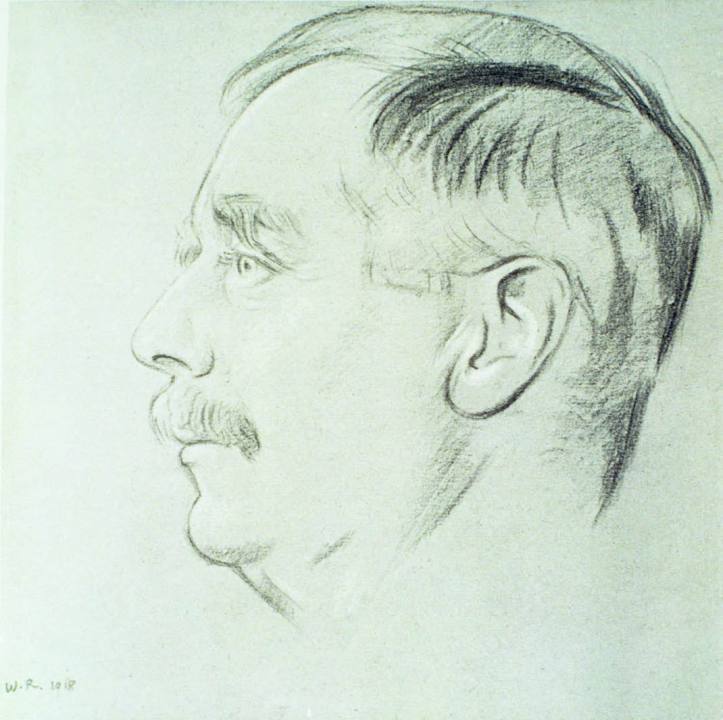

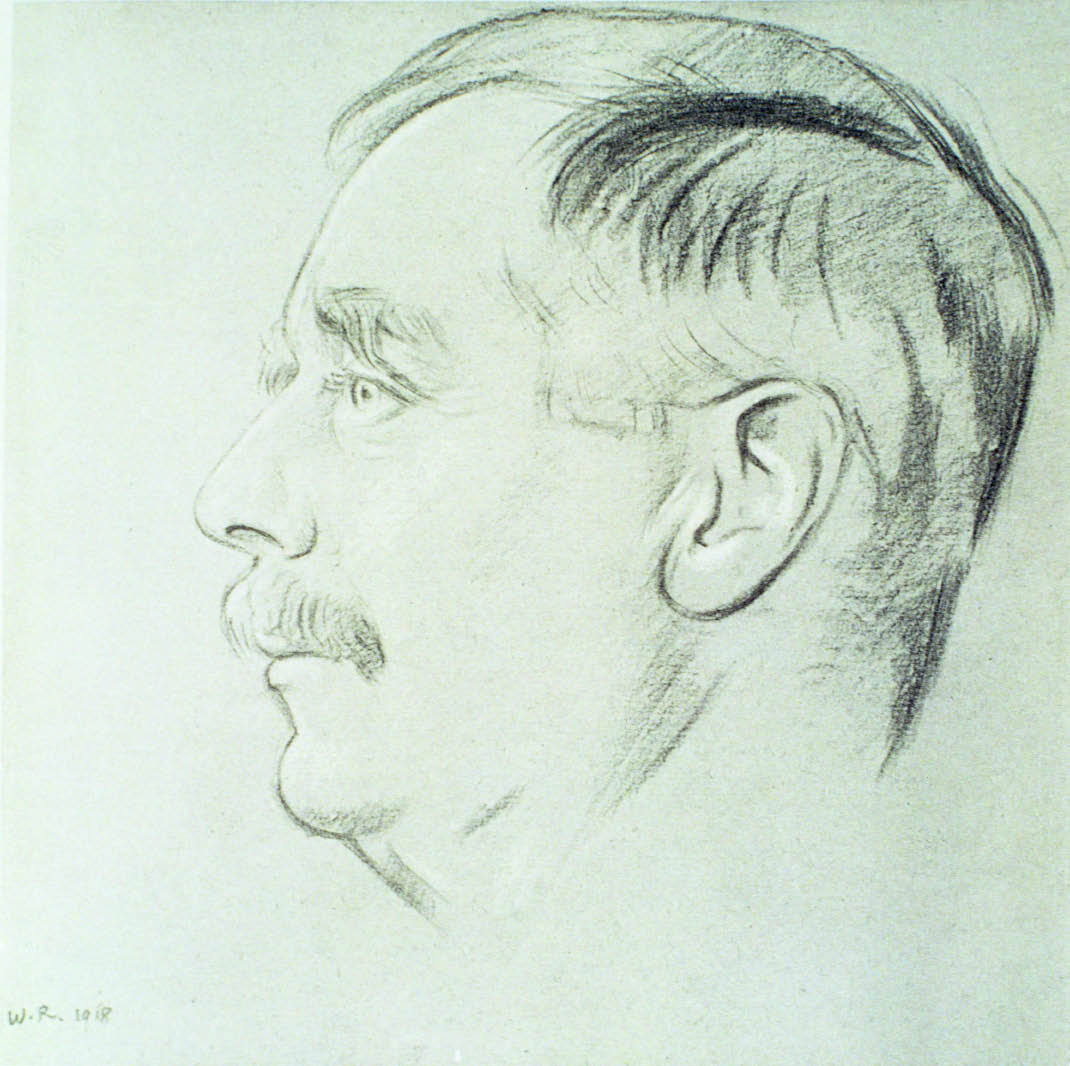

Sam Leith explores H. G. Wells’s addiction to free love, as revealed in David Lodge’s latest biographical novel

In the history of seduction, there can have been few scenes quite like this one:

‘Am I dreaming?’, she said when she opened her eyes.

‘No,’ he said, and kissed her again.

‘But what about Jane?’ she said. ‘You love Jane.’

‘Yes, I love Jane, and Jane loves me, but there are many kinds of love, Amber. You’ve read A Modern Utopia, you’ve read In the Days of the Comet, you know my views on free, healthy, life-enhancing sexual relationships. Jane shares them.’

They embraced and lay in eachother’s arms, exploring and gently stroking eachother’s bodies like blind people. It was an intensely erotic experience.

‘Is that your…?’ Amber whispered.

‘That is my erect penis,’ he said, ‘a column of blood, one of the marvels of nature, a miracle of hydraulic engineering.’

‘It’s enormous,’ she said.

No wonder H. G. Wells was a hit with the lassies! A reading list of his own work ever at hand to whisper, sweet-nothing-style, into a young lady’s ear; a shrewd understanding of hydraulic science; and a huge cock: he had them all.

In an age when many on the Left were theorising about free love, Wells was doing everything he could to practise it. His incurable goatishness is front and centre in this novelisation of his life, and an epigraph from the Collins dictionary makes explicit the bawdy pun on the word ‘parts’ in the title.

With the gritted-teeth toleration of his second wife, Jane, Wells had affairs with the wives and daughters of friends, passades with prostitutes and fans, and an all-star bunk-up with the young Rebecca West. He was incapable of keeping it in his trousers. That did all sorts of damage to his reputation and his career in Fabian politics. But it also posed questions: was he a lecher or an idealist? An exploiter or a tender romantic? Selfish or noble?

David Lodge’s book allows him to ask those questions of himself. The set-up finds HG on or near his deathbed, looking back in between long chunks of flashback, telling the story of his life in chronological order, a voice, sometimes accusatory and sometimes drolly condescending (his conscience, you find yourself assuming), conducts a Q & A interview.

A sample:

— ‘The War That Will End War …’ That didn’t enhance your reputation as a prophet.

— Oh, don’t rub it in.

The effect is of a book-length version of This Is Your Life, and the walk-on cast — which, apart from Rebecca West, includes Ford Madox Ford, Beatrice and Sidney Webb, George Bernard Shaw and Henry and William James — is often wonderfully represented in quotations from letters and articles.

Every time Henry James — the subject of Lodge’s previous fiction/faction excursion, Author, Author — turns up, for instance, he steals the show. When HG publishes a book, James invariably writes him an elaborate, sinuously backhanded compliment to the effect that it’s so delightful it has entirely paralysed his critical faculties. HG is content to get his own back by mentioning his sales. Then, towards the end, open warfare breaks out. James characterises HG in print as a hack throwing random rubbish out of windows at passers-by; HG strikes back by describing James as a hippopotamus lumberingly determined to pick up a pea.

The letter of reproach that James writes, especially given that he and Wells were still unreconciled at the time of James’s death, is powerfully poignant. You find yourself suspecting that Lodge is fundamentally more interested in James than Wells. But as a writer, here, he’s rather more like Wells than James.

The story zips along engrossingly, and it is as interesting as its subject, but James’s attack on Wells — that he achieves ‘value by saturation’, squeezing ‘to the utmost the plump and more or less juicy knowledge of a particular acquainted state’ — seems to apply to Lodge’s own method here.

The problem is that A Man of Parts is so like a biography — particularly given the imaginative-reconstruction school of novelistic biography that now seems to be everywhere — that it’s sometimes hard to see what it does as a novel that greatly adds to that. Lodge says in an author’s note that all the establishable facts are as per the historical record, and page after page passes that could be from straight life-writing of the old-fashioned sort: putting the facts in their place, adding a little historical context, and having in the style that distinct non- fictional feel of précis (hard to pin down but you know when it’s there).

Where Lodge descends to ground level — to what you might think of as the novelist’s distinct terrain — the style is admirably egoless: pane-of-glass pellucid. There’s little or no writerly vamping about, and the narration is on the border between third-person-omniscient and free-indirect, hovering around the edges of Wells’s thoughts like an overly polite under- butler. Lodge clearly has a deep knowledge of HG’s life and a very plausible understanding of his psychology. But it’s Lodge’s voice you hear, rather than HG’s.

And where you do notice the writing, dismayingly, it’s a bit potboilery. Dialogue is introduced with ‘he expostulated’, or with redundant qualifiers: ‘he said angrily’, ‘she said cheekily’, ‘Amber said eagerly’, or at one point ‘ “Isn’t it wonderful?” Maud Reeves cried enthusiastically.’

There are sentence-length clunkers, too:

Anthony rings up Jean, a pretty young brunette with superb breasts who works as a secretary at Bush House, with whom he is having a passionate affair, and tells her the news about his father.

Or this:

‘Don’t be so mean, Mother! I’m not making it up!’ said Amber, and flounced out of the room. Maud raised her eyebrows and sighed. ‘Young girls! They’re so sensitive.’

Or this:

When their sexual starvation had been allayed by several bouts of torrid jungly intercourse, they turned their attention to practicalities. Rebecca had not corresponded with Llandudno in his absence…

Or the almost Adrian Moleish:

She murmured incomprehensible but exciting Russian words and phrases as she reached her climax and he released the pent seed of three weeks’ abstinence into a sheath he had prudently brought with him from England.

No book of 500-plus pages, of course, will be without the odd gauche line and it seems mean to pick nits like this, but it is something you notice as a reader, and it gives you the sense that Lodge hasn’t made his characters his own, or worked through his prose as fully as they need.

And if the style of the book is workaday, its dramatis personae understood rather than inhabited, and its shape essentially dictated by its subject’s real-life story, I’d say it’s closer to a biography than a novel. It’s a good biography. I read it with entire interest and enjoyment, and learned a lot about H. G. Wells. But as fiction it seems, in Robert Lowell’s words: ‘Heightened from life/ yet paralysed by fact.’

Comments