With ministers behaving particularly oddly, we thought CoffeeHousers would enjoy Matthew Parris’ Spectator column from May, in which he explains the weirdness that afflicts politicians.

With ministers behaving particularly oddly, we thought CoffeeHousers would enjoy Matthew Parris’ Spectator column from May, in which he explains the weirdness that afflicts politicians.

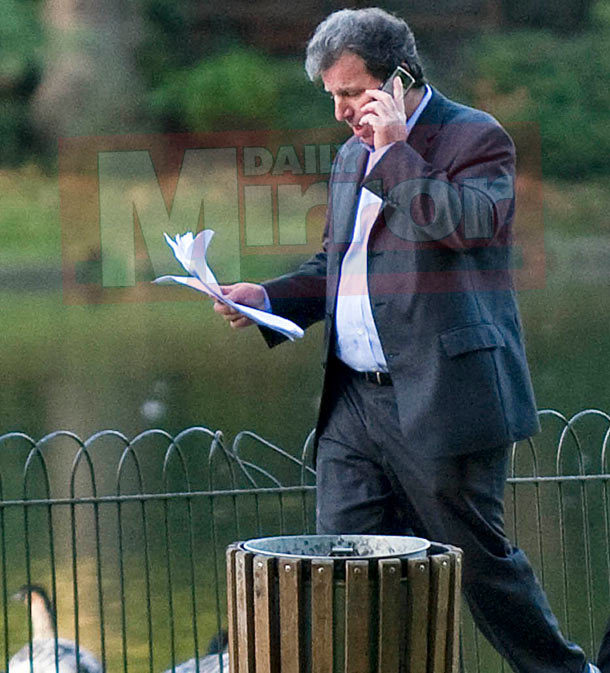

Politicians are not normal people. They are weird. It isn’t politics that has made them weird: it’s their weirdness that has impelled them into politics. Whenever another high-profile minister teeters or falls, the mistake everyone makes is to ask what it is about the nature of their job, the environment they work in and the hours they work, that has made them take such stupid risks. This is the wrong question. We should ask a different one: what is it about these men and women that has attracted them to politics?

On the whole, by and large, and with any number of exceptions, individuals drawn to elective office are driven men and women: dreamers, attention-seekers and risk-takers with a dollop of narcissism in their natures.

Why wouldn’t they be? They’ve self-selected. Consider the odds. You hang around for years, forsaking other safely lucrative career ladders, in the hope (statistically unlikely to be fulfilled) that you will be chosen as a parliamentary candidate. Then you run for election in the hope (statistically uncertain) that you’ll be elected. Once elected you hang around again, now in a nervously exhausting but intellectually unchallenging job (the role of backbencher) in which you’re treated like a prince in your own patch and like scum by whips and ministers at Westminster — all in the hope (and yet again the odds are against you) that you’ll become a very junior minister; in which often wretched post you hang around for a few years more,

still poorly paid, still little-regarded by colleagues, in the hope (the odds now even more heavily against you) that you’ll reach the Cabinet.

And through all this time you are obliged to submit yourself every four or five years to the caprice of your constituency electorate; all around you lie the bodies of promising politicians turfed out by the voters just as they were beginning to rise.

Even if you clear all of these fences you will never be well paid by the standards of those bosses in the world outside with whom you deal as equals; while most Cabinet ministers (as you very well know) never get much further, take their statutory knighthoods, become Right Hons, and slip away into the night, described by colleagues and commentators as having ultimately failed.

As I’ve so often written, elective office feeds your vanity and starves your self-respect. What, then, are the compensations that — for those who choose this life — make it all worthwhile? They are these. First, a craving for applause, for being a somebody, for being looked up to. The read-across from this to the sexual behaviour of middle-aged men in politics is too obvious to need stating: power is indeed an aphrodisiac: but for the powerful, for the predator rather than his prey. It’s like having a big sports car.

Second, a completely and persistently unrealistic belief in your own good luck. You know the odds, you can calculate the statistical likelihoods, but for you it’s going to be different. Someone up there is watching over you — you really do half believe this. Even when all seems lost, you tell yourself that maybe a miracle will happen and you’ll slip through the net. You’ll get by this time. You always have before.

Third — and this is truly weird — an awfully thin skin. You keep getting hurt. You read about yourself obsessively. Every insult stings. But you self-harm, throwing yourself back into the ring for more, then reading the papers again: you don’t know why, and your wife or husband really doesn’t know why.

All this leads to frequent pain, frequent euphoria, a hopelessly optimistic estimation of your chances, and an obsessive-compulsive drive to keep asking for more until something — something big and external to yourself — finally fells you. Like any addict, you’re half yearning for this to happen.

Some of the people answering the description I’ve just offered have been very great men and women indeed and achieved very great things. Some have been total idiots. And not a few have been both.

Comments